Tidskapsler - København i 1990'erne / Time Capsule - Copenhagen in the 1990s

/It was strange but a huge amount of fun to walk round this new exhibition at the Museum of Copenhagen.

There are more than 700 time capsules here - compact perspex boxes - 16x16x26 centimetres - that were produced in 1996 - in the year that Copenhagen was the European City of Culture - and then stored away with a promise that all would be revealed after 25 years.

Before going to the exhibition, I would have said that I remember the 1990s quite clearly. However, half the time, objects in the capsules looked so familiar that surely this was all only yesterday but then I'd see something I'd forgotten all about and, with that shock of remembering, I'd realise it really was all a life time ago ... just how could anyone have done that, worn that or used that or could ever thought that seemed normal.

In one time capsule, there was a membership card for Blockbusters and I had completely forgotten about the ritual trip down to the store, literally a block away, on a Friday or a Saturday afternoon to rent a couple of videos if it was going to be a quiet evening.

And it was clearly a very different time and a very different city because, back in the 1990s, Copenhagen was on the brink of bankruptcy with high levels of unemployment. The port had been in decline for at least a decade and much of the housing in the city, particularly in Vesterbro, was very rundown.

Many who could, had abandoned the central districts and moved to new suburbs like Rødøvre or Lyngby. In 1950, there were around 768,000 people living in Copenhagen but the population declined through the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s and by 1990 there were only about 465,000 people living here. That’s a significant decline.

With hindsight, the turning point may well have been when Copenhagen was chosen as the European Capital of Culture in 1996. That triggered new investment in culture and it was certainly seen as a way to stimulate tourism but there would also be important, long-term gains.

Film making and theatre in the city and art and literature were reinvigorated and there was a new optimism in planning and development.

The city began to see the harbour as a potential resource with important new projects for civic building along the harbour with work starting on an extension to the national library that was to leap the old port road so, instead of looking inward to a garden and to the parliament buildings, it staked an early claim to the water frontage. Work began on a new opera house at the centre of the inner harbour and new developments of office buildings were started on either side at the south end of the harbour, including on the site of the old Burmeister & Wain engineering works immediately below Knippelsbro and, below Langebro, along Kalvebod Brygge, on the city side, and along a new harbour park - Havneparken - on the Amager side.

Presumably, back in 1996, the idea behind these time capsules was not just to capture that moment in time - the zeitgeist - but were a way to make people focus on what was good or bad about their lives in the city and perhaps decide what was important for the future.

Individuals and all sorts of societies - including schools, clubs and workplaces - made time capsules and the boxes are filled with an incredible range of objects from condoms, to needles from the drug culture in the city, along with music cassettes and, CDs - then a new and more expensive technology for playing music - and there are floppy discs; a spool of labels for adding bar codes and even mobile phones that were then relatively novel and relatively expensive. There are guide books to the park at Frederiksberg and bus and train timetables.

One box has a single capsule of Fontex .... an anti depressant that was, apparently, discovered in 1972 but first prescribed in 1986.

The time capsules are grouped by general themes and these include:

Kulturlivet / Arts and culture

København som filmby / Film City Copenhagen

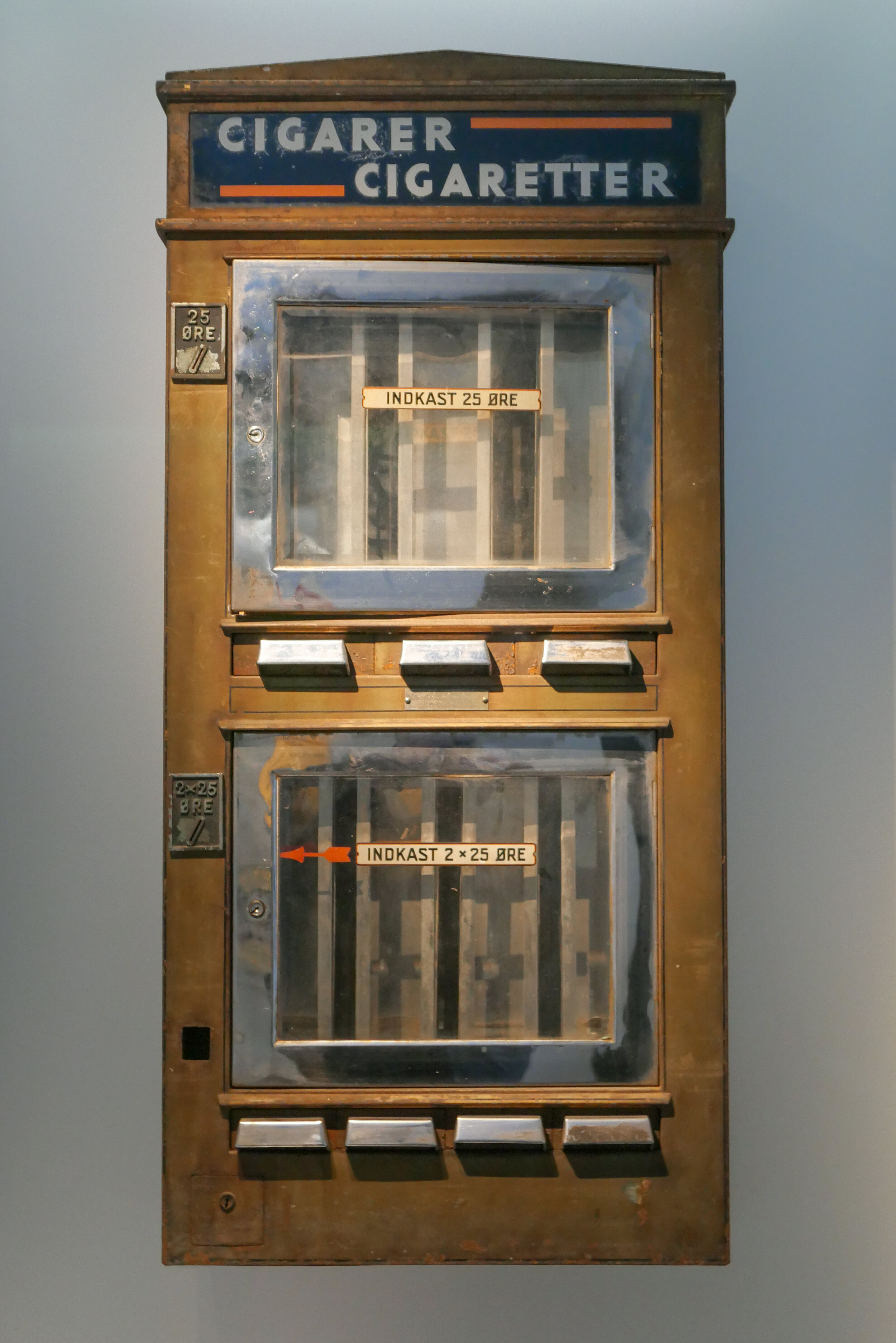

i byen i København / out on the town in Copenhagen

Den Første Pride / Copenhagen's First Pride

Body and Mind

Everyday life

Hiphop

Comedy

Alongside the time capsules are photographs and larger objects from the collection to provide a context with separate sections reflecting many aspects of popular culture and particularly music and club entertainment.

Major cultural events and trends discussed include the Dogme Collective of film makers - Lars von Trier, Thomas Vinterberg, Kristian Levring and Søren Kragh-Jacobsen - and there is a director's chair with the name Lars von Trier on the back.

Display panels alongside the time capsules explain the emergence of grunge and techno and a fast-developing and rapidly changing youth culture with amazing artefacts like pairs of Dr. Martens boots and Buffalo Boots.

Copenhagen was the first city to launch free bikes that were financed by adverts. They could be unlocked with a 20 DKK coin that was returned when you returned the bike.

But the exhibition also reflects serious problems and concerns of the time like the aids epidemic. Aids spread through the 1980s and 1990s and in 1996 the first EuroPride - part of a campaign for the recognition of gay rights - was held in Copenhagen and the largest single item in the exhibition is an aids quilt.

The journalist Lasse Lavresen is quoted as saying "The 1990s was a decade of irony when nobody meant what they said, and everybody thought history had been relegated to the past."

In one time capsule there is a sperm sample and maybe, just maybe, that can be seen as ironic - or possibly sardonic - but how many kids put on a pair of Buffalo Boats with the hope that it was seen as a comment on contemporary politics or even as simply a sarcastic gesture? For some, what they chose for their time capsule was a shout of defiance and for others a cry for help but irony? No, not irony but certainly there is a vitality that makes life in the city now seem rather bland in comparison.

Københavns Museum / Museum of Copenhagen

Tidskapsler - København i 1990'erne / Time Capsule - Copenhagen in the 1990s

the exhibition opened on 4 February and continues until 31 October 2022