a Guggenheim for Helsinki

/In The New Yorker on the 12th May there was an astute article by Ian Volner about ongoing uncertainty with the plans for a new Guggenheim in Helsinki. He sets out the problems and quietly poses the questions although, quite rightly as an outsider, he does not and can not suggest a solution but what I found interesting was that his one firm conclusion was that “ … the Guggenheim, with its global reputation at stake, may need Finland more than Finland needs the Guggenheim.”

Is a mega museum, designed by a star foreign architect and showcasing international art, a long-term and sustainable benefit for the city? Is this simply a matter of having to be pragmatic … balancing an income from fickle tourists needing to be entertained before they pay out a dollar or a yuan against gaining what might be an important resource for Helsinki that can be used to inspire young Finnish artists and aspiring Finnish architects? Surely the Museum of Design and the Museum of Finnish Architecture in Helsinki already do a pretty good job of that.

Certainly it would be too high a price to pay if a new building dominated the harbour visually or changed irrevocably the balance of an urban plan that has evolved slowly in response to local and regional needs and pressures. And it would certainly be too high a price to pay if, after an initial enthusiasm, the paying audience moved on to something they thought was newer or more entertaining. Surely, in order to be sustainable in the long term, a new museum has to have at least some local relevance.

I first went to Helsinki in 1974 and returned for the first time forty years later so perhaps I should not make comments about a country I cannot claim to know well but I hope it is reasonable to make one observation: Finland in 1974 seemed cautious and reserved … an amazing and beautiful country and one with strong, distinct architecture based in part on natural and available building materials - in part on the countries own history - in part on the style and influences of it’s neighbours and, in part, in a strong belief in its own contemporary designers and architects. Finns may have seen themselves as isolated but, essentially, they were also self sufficient.

Wandering around the design quarter of Helsinki forty years later that was all still true but there seemed to be a new and clearly justifiable sense of self confidence along with a friendly openness and a willingness to both explain and to discuss what was being built or made but it was, quite rightly, with a strong hint that those designers and makers were proud of what they are doing. You are very welcome … I sensed I was being told … but if you don’t like it that is your problem and not ours. I repeat, it was something I sensed - not something anyone said but the team from the Guggenheim should be and probably by now are painfully aware of that.

Part of the problem is the proposed site. It is close to the city centre and is certainly prominent and handy for tourists arriving by cruise ship but it is a curious mixture of urban architecture and relatively small-scale maritime buildings on the quayside backed by trees and it is certainly not an abandoned industrial site where any solution would be better than nothing. A building or group of buildings that is grandly civic or something that is vernacular in scale would both be inappropriate for the setting but then also surely a pastiche of maritime buildings would hardly seem to be honest or appropriate as a home for international art and a magnet for tourists.

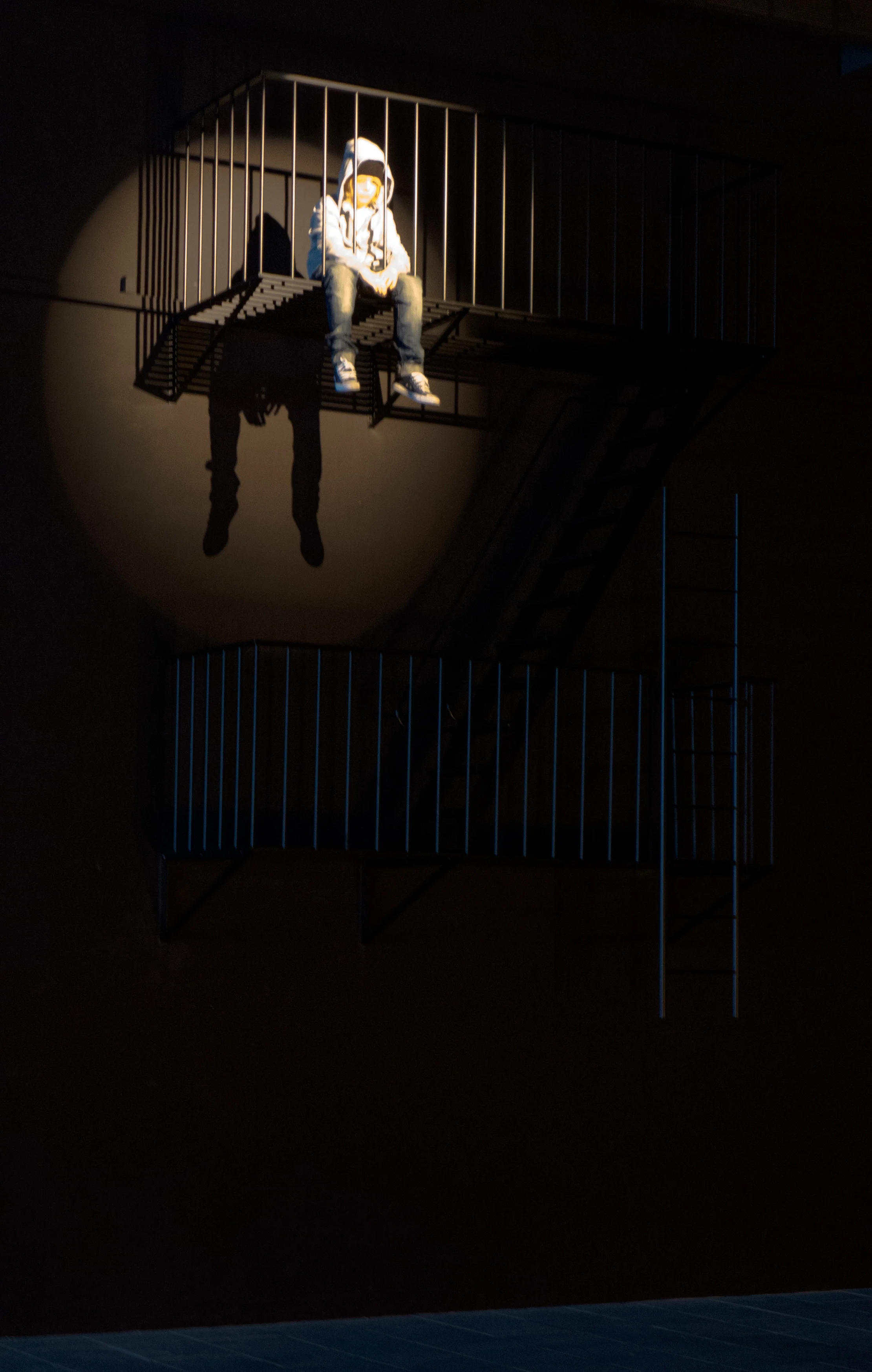

One building I visited in Helsinki that still seems physically like a slightly awkward visitor is Kiasma - the museum of contemporary art. As a facility a new Guggenheim must be relevant and useful for and used by the citizens … otherwise it simply has the role of a new Hilton or a new Marriott: something a local might or might not use but probably not and is essentially something that is there for the visitor who arrived yesterday and will be gone tomorrow. The new Guggenheim, as a structure, has to be firmly anchored in the design ethos and architectural traditions of Finland … if not it will be a bricks-and-mortar version of an ugly cruise liner in the harbour that everyone hopes will sail away.