There I Belong at Statens Museum for Kunst

/There I Belong is the first in a new series of exhibitions under the title SMK Plus where contemporary artists will explore the collections of the National Gallery.

For this exhibiion - Inspired by the works of the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi who lived and worked in Copenhagen around 1900 - the artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset have collaborated with Marianne Torp and Tone Bonnén, the museum's curators of contemporary art.

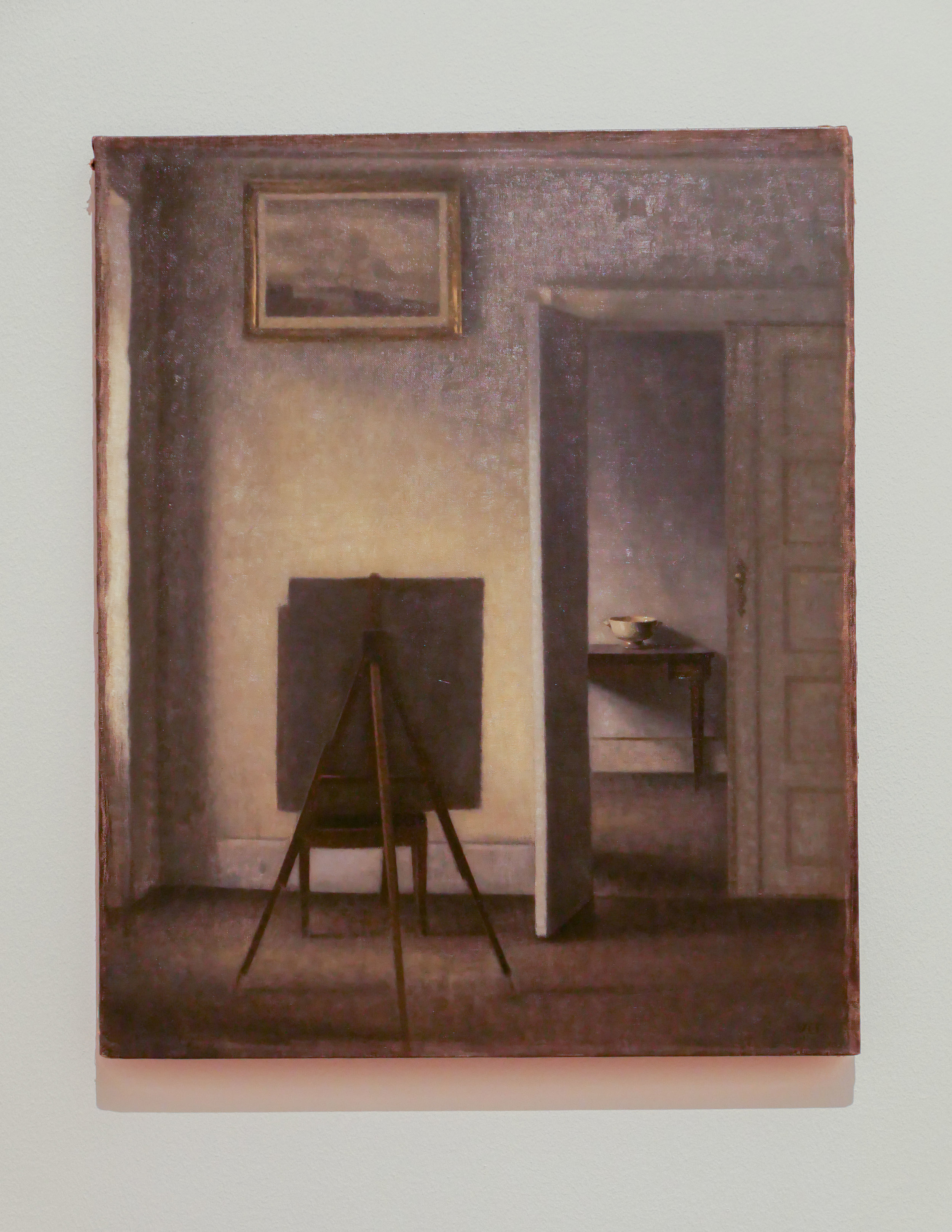

Spartan interiors by Hammershøi are restrained and calm but they are enigmatic - paintings that tread a fine line between being self contained or depictions of a life of painful isolation. The paintings resonate with a contemporary audience, reflecting aspects of modern taste and restrained Scandinavian interiors.

There may be windows in these rooms but the view out to a world beyond is usually obscured by thin, translucent curtains … the natural light entering the room is crucial but a sense of place not so because these are studies in light but never put people, objects or place under a harsh spot light. Figures in the paintings are detached, generally absorbed in what they are doing, inward looking, often with their back to the viewer and in many of the paintings we do not even know if they are reading or writing or simply sitting with head bowed in quiet contemplation. Open doors indicate that there are rooms beyond but barely hint at a lived life.

Interior with the Artist's Easel, takes this to an extreme because, when painting the picture, the artist himself should be at the easel. The only conclusion has to be that there is a second easel at the point where the viewer is standing so are we the artist? Perhaps we have been co-opted into this quiet and private world but this is the ultimate antidote to that modern scourge - the selfie - where the photographer shows themselves at the centre of the scene, always the subject of the view, inevitably relegating an event or scene beyond to a secondary role.

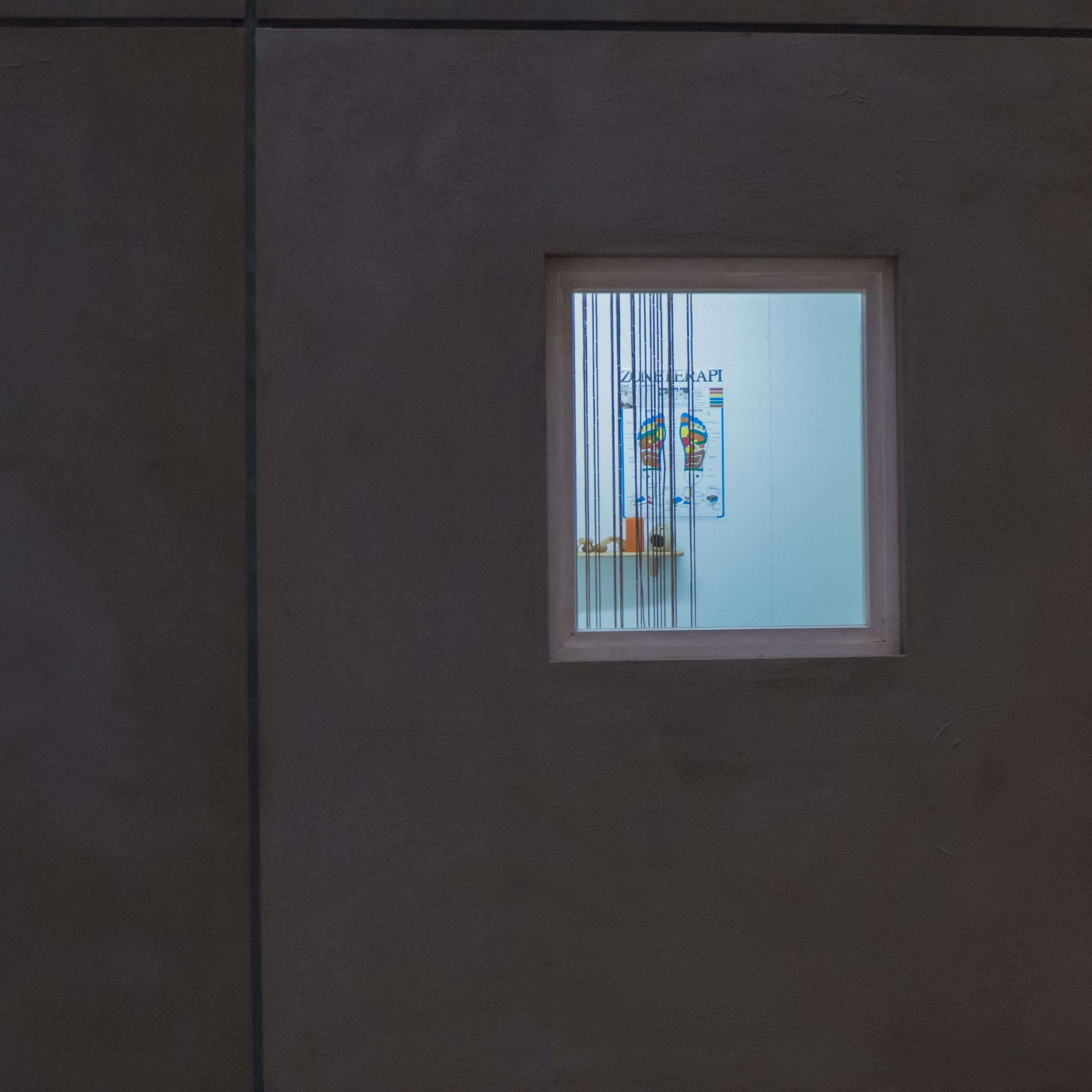

The second gallery - a large space - shows the work Powerless Structures (8 doors) by Elmgreen & Dragset from 2000-2002. These are the most simple, basic, standard white doors imaginable, with plain white door frames but each is a variation in a theme of a detachment from the real or the functional … one door has handles and hinges on both the left and the right side so it would be impossible to open - another has a handle that is not on the door but on the wall alongside so it might or might not open - one door is slightly open to reveal a locked door immediately behind - one door is folded and wrapped around the corner of the gallery - a pair of doors on adjoining walls at another corner are separate but linked by a security chain as if someone might be able to squeeze through from a room on one side to another room without being able to get into the gallery.

This work, or a version of this work, was shown at Statens Museum for Kunst in 2015 in Biography - an ambitious set of major installations by Elmgreen & Dragset. Then, the doors were part of a corridor and a series of rooms that were in what appeared to be a government or public office building. If not obviously dystopian then the corridor was completely anonymous and designed to smother any sense of self. On entering you had a choice to go one way or the other but with no signs or notices to say where you were or why you were there although you could get a ticket from a machine to wait for your number to be called but it never would be, of course, and if you proceeded past these doors you could only return to where you started.

By now placing these doors on the four walls of a large gallery, the work takes yet another step back and pays homage to Hammershøi but expands his space until it is monumental in scale.

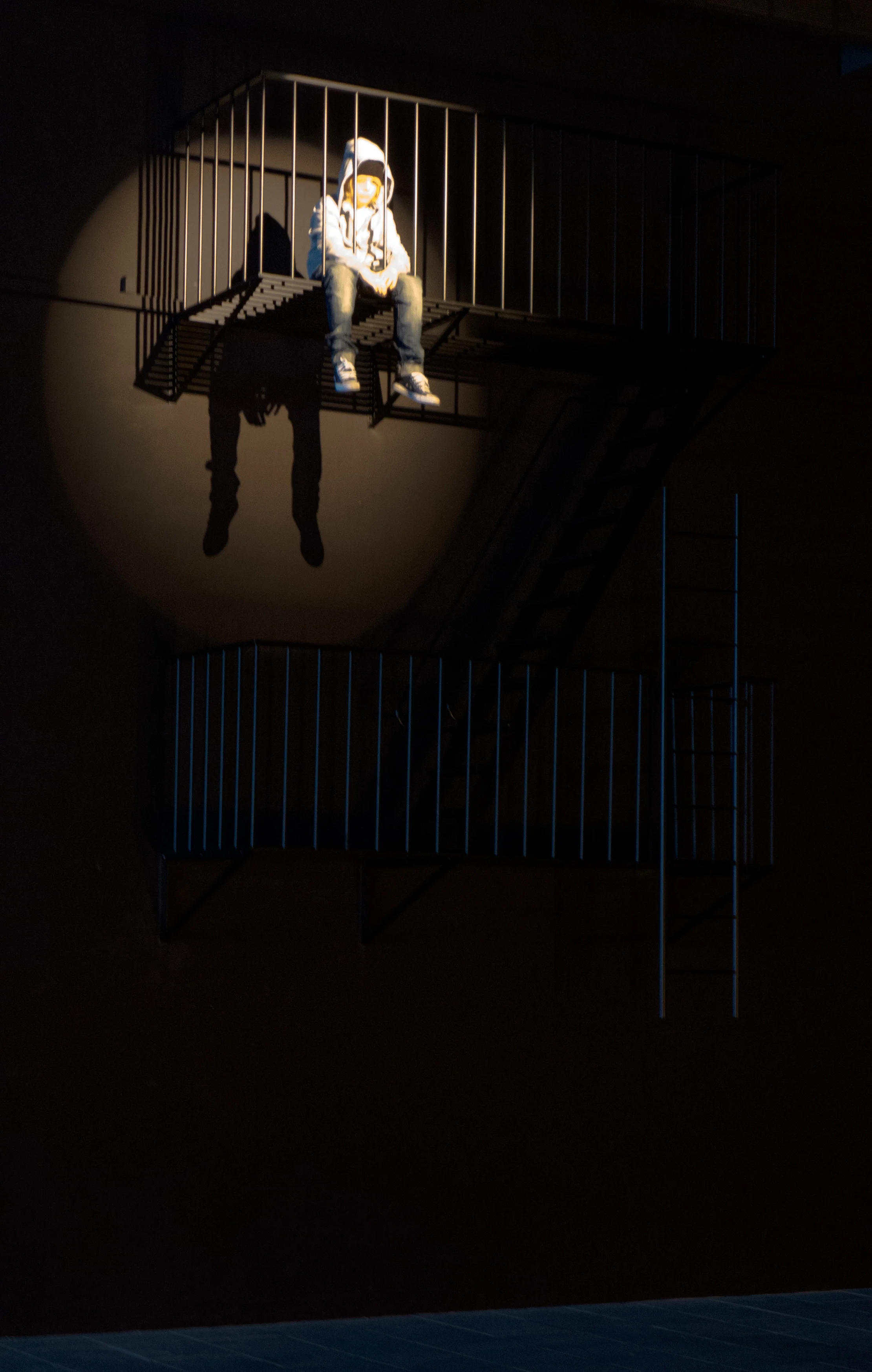

The exhibition includes photographs, paintings, sculptures and video by other artists - all taking the theme of doorways and spartan anonymity - with works by Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Lilianna Maresca, Francesca Woodman, Robert Gober, Annika von Hausswolff, Ugo Rondinone and Thomas Ruff. Only the work by von Hausswolff is from the museum collection with the other works either courtesy of the artist or on loan from galleries and private owners.

the exhibition at Statens Museum for Kunst / The National Gallery in Copenhagen

continues until 1 September 2019

Interior with a young woman sweeping, 1899

Interior, No 30 Strandgade, 1906-1908

Interior with the Artist’s Easel, 1910