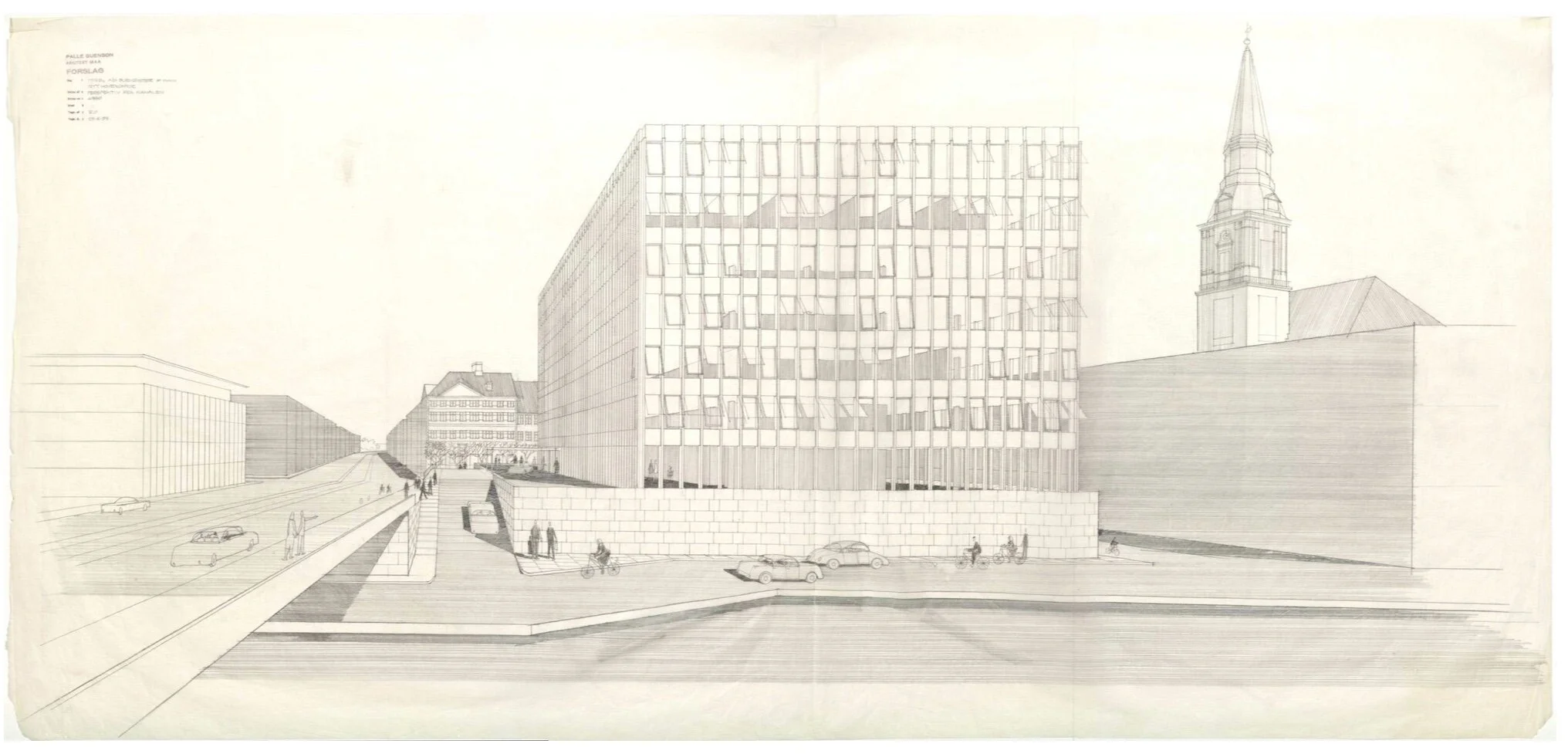

update - Hilton Hotel on the harbour

/Work is moving forward to convert the old Nordea Bank offices for a new Hilton Hotel on this prominent harbour site by Knippelsbro. Now you can see just how high the extra story will be and you can see just how the hotel will break through to the quay - to colonise it as an attractive new feature - a valuable commercial asset - for the new hotel.

And in return ……… the city gets some new steps down to the quay from the bridge.

The old office building was much too big and, with hefty concrete cladding, brutal and ugly but in part it was those things for clear reasons. When it was constructed in the 1950s, the harbour was a working port and not a tourist destination and this was the offices of the Burmeister & Wain ship yard that was crucial for providing jobs for the city and was a major player in the post-war effort by the country to restore the economy. Looking pretty was not on the design brief.

But right here, right now, if the Hilton Group had cleared the site and started again, a scheme for a building of that size and in that position would not be given planning permission.

And then they pushed the boundaries by asking for and getting permission to add an extra floor on a building that was already too big.

Until last year I lived in an apartment buildings to the south, behind the church, and looked out across the top of the trees in the churchyard with a clear sky line broken only by the church tower and with no one looking in. Then work started and the Nordea building took a deep breath and puffed out and began to loom over the trees.

Those apartment buildings are not the most stunning design but they are well designed and carefully designed to create pleasant living space and good streetscapes on land where there had been dry docks and sheds that no one could see a way of preserving after the yards closed. More to the point, planning controls kept the apartment buildings to the same overall height as the gutter or eaves of the church …. so not to the overall height of the church roof and not to the overall height of the spire but to the height of the body of the church. That development showed at least some respect for the historic buildings that still do and still should dominate the area.

In the general sweep of things I'm only a visitor to the city so it is not my place to be offended on behalf of københavnerne - who are certainly more than capable of defending their own values - but there seems to be something basically undemocratic about these huge international hotels that break the spirit if not the letter of Janteloven. The Hilton will make use of the nearby metro - though I guess most guests will arrive by taxi - and the ferry is at the back door to serve hotel guests and the quay will make a ‘picturesque’ backdrop from their harbour-side café or bar but I'm not exactly sure what citizens get back in return. Presumably, that huge glazed new top floor will be expensive restaurants and spaces for events but how many people in the city will ever use that unless they go just once to see what is up there. They don't need another ‘new perspective’ to see over their own city or a viewing platform to look down on their fellow citizens.