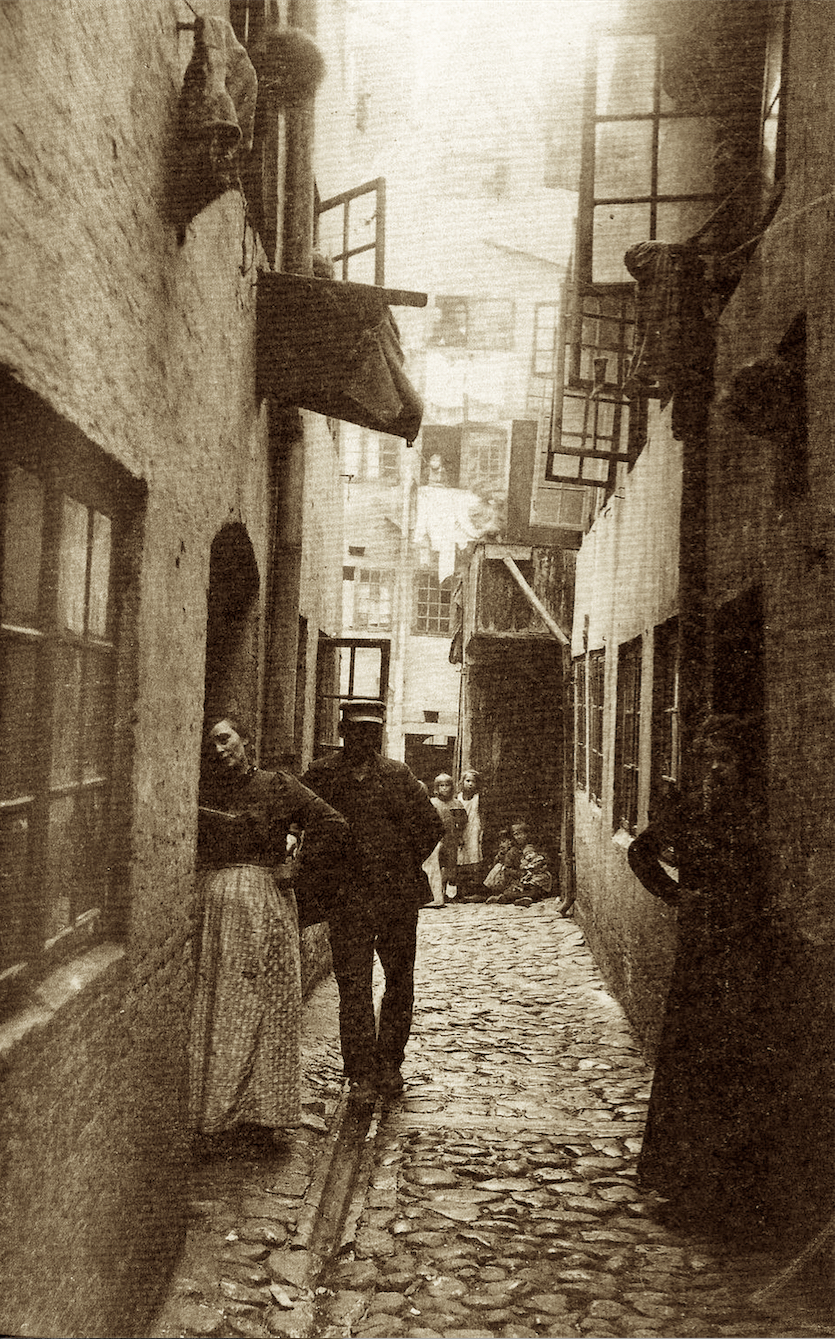

One area of tightly-packed houses and alleys just west of the King’s Garden was notorious for not just its slum housing, “suspicious characters” and public houses but through the 19th century it was said to be the part of the city with the most blatant and open prostitution described in the newspaper Socialdemokraten in the 1880’s:

”Lille Brøndstræde consists of a collection of shacks, 7 of which are brothels that however usually also house other residents than the tarts and their hosts. Anything more disgusting and miserable than these huts is hard to imagine …the shared characteristic of these buildings is decrepitude and limited conditions, which allows the sin and dirt the most excellent conditions for a fertile life ... The first thing, which stops the visitor is the darkness and the stench from the gutter or the filth in the yard. Light can only be mentioned once you have elevated a little and the air in these back building residences never gets sufficient renewal.”

If you are curious to seek out the street, the buildings there were demolished sometime after 1900 and if the ghosts of the women and their pimps are to be seen anywhere it will be in the Danish Film Institute built on the site.

So just how densely packed with people was Copenhagen?

In the 1840s - so shortly before the outbreak of cholera in the city - the population of Copenhagen has been calculated to have been about 120,000 people but of course then Copenhagen was much smaller than now - just the inner city, the new town around the royal palace and Christianshavn. Both the latter areas were relatively spacious with large houses and both Holmen and Gammelholm, south of Kongens Nytorv, were working docks and ship building yards so few lived in those parts. It is difficult to find the figures to compare like with like but the old city from the east gate, by what is now the Hotel Angleterre, to the west gate, close to the city hall - so the length of what is now Strøget or the walking street, is about a kilometre and from north to south, from Nørreport to Gammel Strand, the old quay, was only 750 metres and the irregular shape meant that the area was much less than a square kilometre although, even in the 19th century, there were some large squares, some broad streets and of course public buildings. There were probably getting on for 100,000 people living in that area.

To give that some context, the most densely-packed area of modern Copenhagen is Inner Nørrebro where the most recent figures suggest that 31,000 people live in an area of 1.72 square kilometres … so in the centre of Copenhagen in the middle of the 19th century, at the time of the cholera epidemic, there were more than three times the people living in less than half the space. And that was at a time when there was no running water and no sewerage system.

If I have just alienated all my Danish friends by implying that their beautiful city was some sort of seething slum in the 19th century, then I would hasten to point out that parts of Paris, much of east London, large parts of Hamburg and Amsterdam were just as densely packed with people at that time. To placate Danish friends and alienate French friends I would also point out that in Paris the authorities feared revolution in their overcrowded city so, in the middle of the 19th century, demolished densely built-up areas and laid out wide new streets, the boulevards, in part so they were too wide for people to build barricades and so that troops could be moved quickly around the city to quell rebellion while at the same time the authorities in Copenhagen decided that one good way to stop a revolution was to keep Tivoli where the workers of the city would be entertained and distracted. To placate my working class friends and alienate my middle class friends I would suggest an interesting but impossible social experiment: 103,000 people live in Frederiksberg - now seen generally as the poshest part of the outer city - so just about the same number as lived in the centre of Copenhagen in the middle of the 19th century, although they have about 12 square kilometres of space. It would be fascinating to see how they would cope if they all had to move into the central area of the city with something like 8% of the space they have now.

To be rather more serious, Jan Gehl - who has done more than anyone else to analyse the plan of the city and its history and look at how it now functions - thought that because so many people live in the centre of Copenhagen - more than in most European capitals - it feels more friendly, more open and more secure at night. He calculated that in 1995 there were 6,800 people living in the centre and I can’t believe that figure has changed much in the last 20 years so less than 10% of the population 150 years earlier.