I don't mean serious as in grim and pessimistic but that writing about architecture and design on the internet can be much more grown up and more challenging - it should make us think and make us want to understand more - and could certainly be much more about the world we really live in.

Both design in general and our built environment in particular are too important to be limited to a finger swipe in a bored moment and certainly what's posted should be less about envy and aspirations that can't be realised - swish images that just make us, the readers, increasingly more discontented with our own life and encourage us to go out to buy something that will, we are told, make life easier or better or make us look more stylish or more fashionable.

Don't get me wrong, Instagram and Pinterest are good if people want to use those apps to create 'mood boards' for inspiration and as a starting point to find out more. But there should be more.

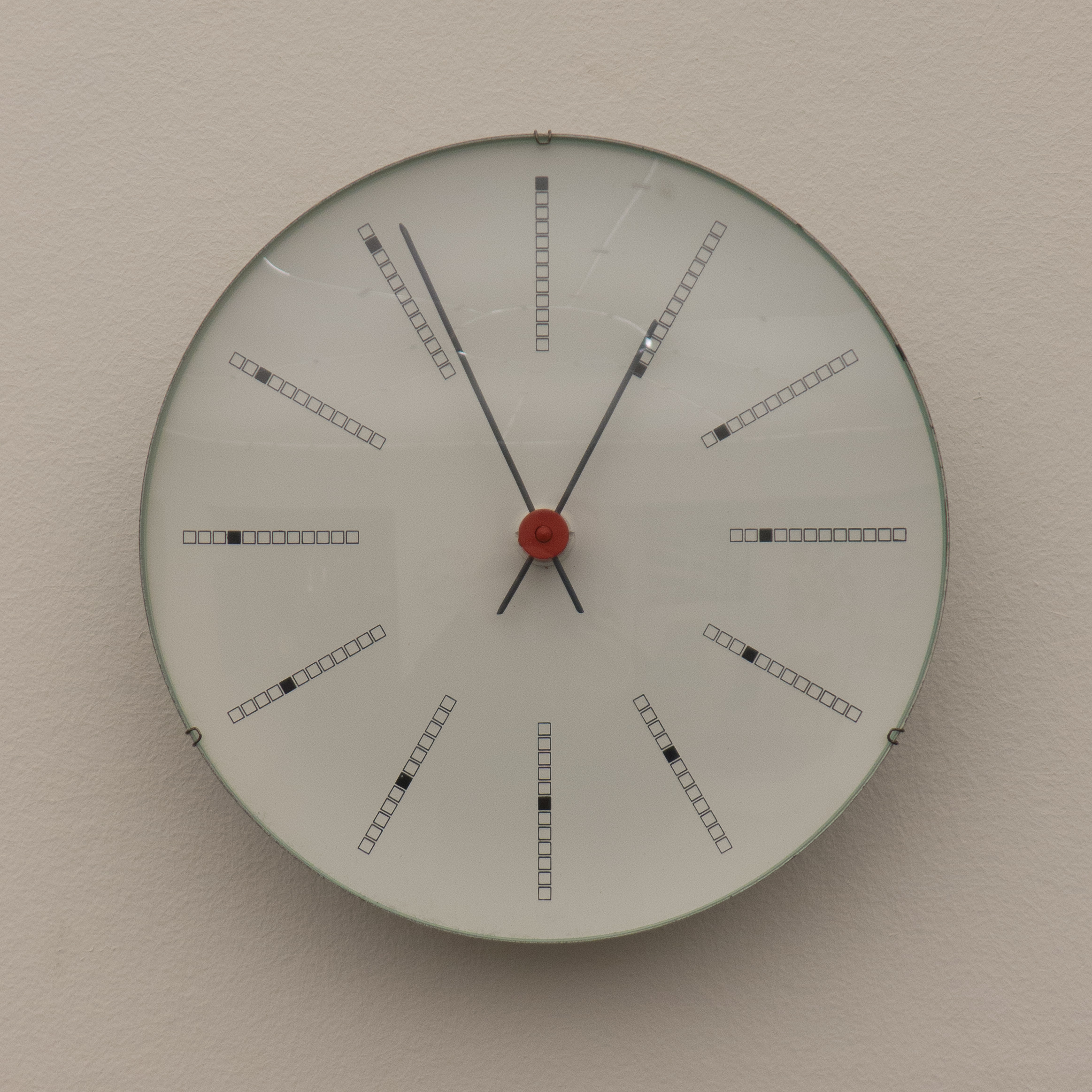

Good design should be about making things that work in a better way or to encourage design that uses materials in a better way, and certainly blogs about design should be much more about looking carefully at what makes good design good and bad design bad so we become more discerning about what we want and what we buy.

For most of us, urban settlements rather than the countryside are our normal everyday environment so the buildings we live in, work in or use for shopping or leisure and the streets and squares that form the settings for those buildings are definitely important. They need to function properly and if they look good and make our lives better or easier it really is a bonus.

Perhaps we all need to look more carefully at the buildings we use in order to understand more and question more about what is going on in our built environment so we can decide what is good and what is poor architecture and we should expect and demand more.

If we don't look at the underside of the table; if we don't plonk down in the sofa before we buy it; if we don't look at the label to see that the materials are genuine and sustainable; if we don't say no, that doesn't work; if we don't see that it's a cheap and nasty copy; if we don't look up from the shop window we are walking past to see if the street is a pleasant or an unpleasant place to be and if we don't start understanding more and questioning more then we end up with the architecture we are given and the design we swipe through on our phones when we have nothing better to do.