A new exhibition has just opened at superobjekt gallery in Borgergade in Copenhagen.

Seven well known and well-established Danish designers were asked to produce objects or installations that reflected a theme of time… “to create a physical comment to what time means to them and by that revealing inspiration, thoughts, doubts and references normally hidden in their final work.”

This is a fascinating concept. These designers, in their designs for a font or for dinnerware or for street furniture, invest a huge amount of their time on the commission - on the initial concept, the process of refining their design, the production period and so on - but the final work is clearly fixed in time … it is finished or as Tina Midtgaard, the owner of the gallery who commissioned the show, points out, “no part will be changed, removed or added.”. Ironically, or do I mean very naturally, many designers hope that their works will continue in production and possibly even, become that iconic and rare accolade to be described by critics as “timeless”.

One issue raised recently in posts here is that rarely does the public, the consumer, appreciate the role of the designer and the effort and time they have invested in a project. Some designers are complicit in that, modestly stepping back from their works. Somehow it seems better to imply that it was easy natural skill and talent rather than hard work that was required. Occasionally a retrospective or a new book will catalogue the range and extent of a designer's work and show all the intermediate stages and the development sequence that led to a well-known design but that is still relatively unusual.

There is an opportunity here for the designers to produce a single piece, a single statement, and one that moves their work into the area more usually associated with artists … producing a single statement to convey a thought or an impression or a viewpoint on life to stimulate discussion, stop the viewer, make them think. It also gives those outside the design world an insight into the thought processes involved in the completion of a design project.

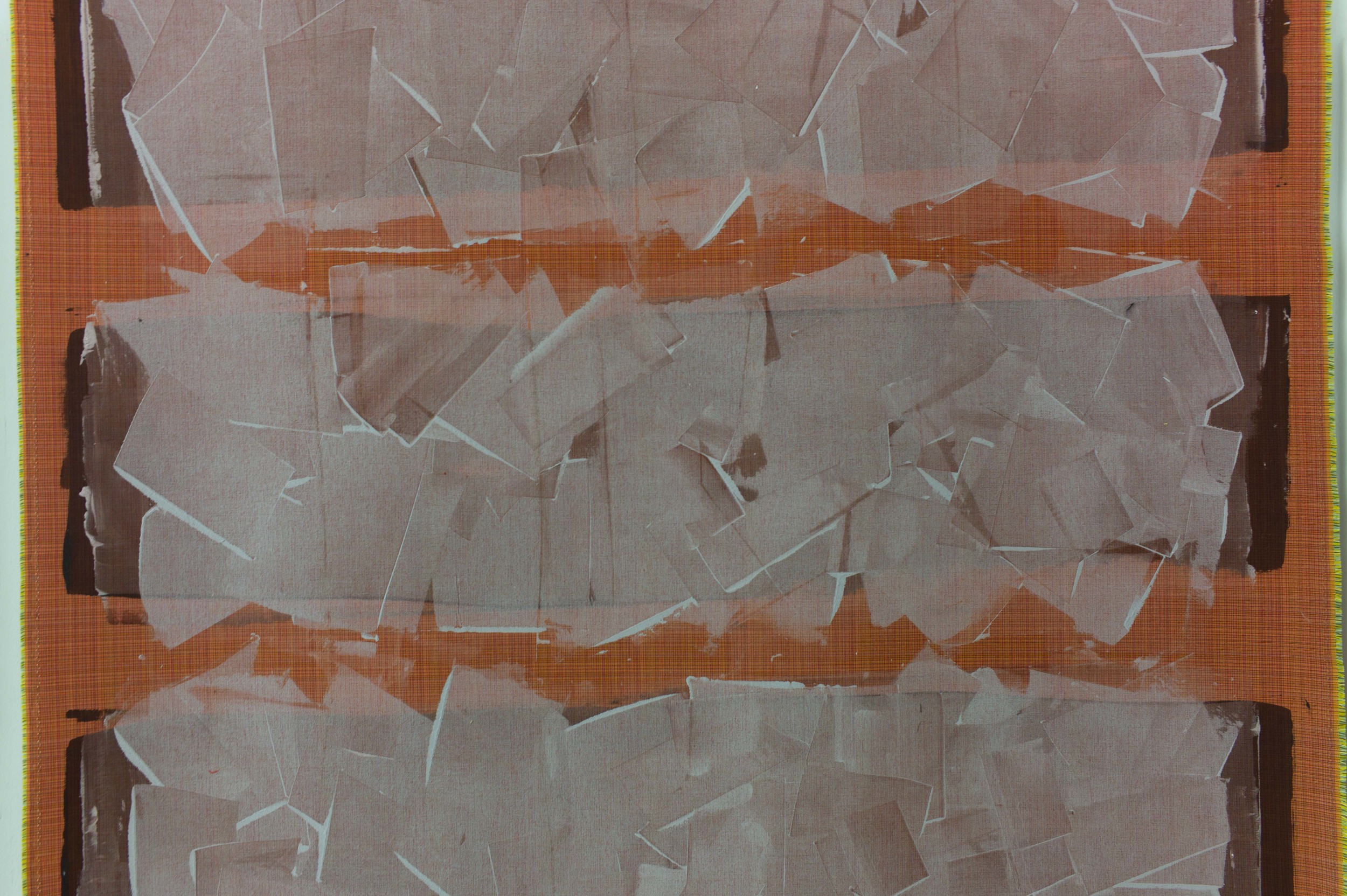

Here, in these pieces, ideas about time are piled up, layered or dissected. And most involve word play. Large posters of food and recipes by Susse Fischer are entitled måITID or mealTIME.