new talent at northmodern

/

A number of young designers exhibited at northmodern.

In part, because they are not long out of university or art school, it was tempting to see their work as closer, in terms of professional development, to pure design theory not yet compromised by the pressures of commercial reality or cynicism. That is not another way of saying these designs were naive … far from it. Just follow the links to the online sites of these designers and you can see just how professional and how focused they are. It is just a way of saying that their view point and ideas were sharp and fresh … as you would expect.

It was also interesting that several were not Danish so, coming from different European design traditions, they introduced a slightly different perspective on design.

Tatous

Valentin van Ravestyn is an industrial designer from Namur in Belgium who trained in Brussels at La Cambre - the renowned school of architecture and the visual and decorative arts that was founded by Henry van de Velde in 1926.

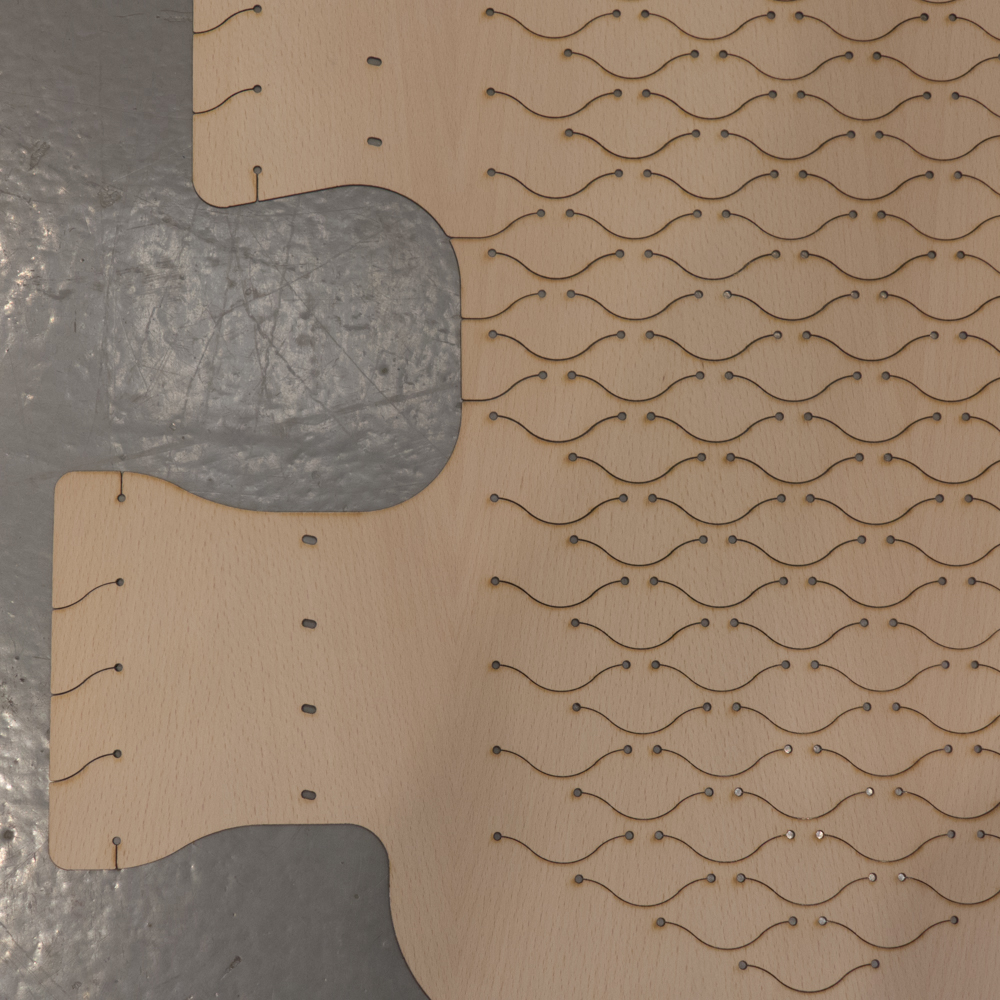

In this project, that he has called Tatous, Valentin has taken thin sheets of plywood and by drilling a regular pattern with pairs of holes that are then linked by a fine, curved cut, he is able to flex and fold and twist the wood so that it takes on the character of a heavy textile and can be used as a covering for furniture, almost like a canvas. In these pieces the wood has been ‘sewn’ or lashed to the tubular-metal frame of the chair or bench with a thick black cord. The result is fascinating, giving the wooden surface a fish-scale like quality or the appearance of a giant pine cone that catches shadow and light in a dramatic way with decorative potential as well as possibilities for completely new uses.

What this work illustrates so clearly is that although man has been cutting and forming wood for thousands of years that does not mean that we have understood and exploited all its characteristics and possibilities.

One role of a designer is to take a familiar material and familiar techniques of working - here simple drilling and cutting - and, with skill and precision but also lateral thinking and imagination, has seen if a different approach, that no one has considered, could produce something new.

Belvedere

Pierre- Emmanuel Vandeputte is also an industrial designer and also studied at La Cambre. His design work includes a bold ceramic cup with the handle formed by an inward curve and a facet back to the main outline that creates a simple indent or ridge for the fingers rather than a loop for a conventional cup handle or there is his starkly simple but beautifully proportioned wine carafe in glass with a straight cylinder, like a laboratory vessel, but with a V-shaped snip in the lip to form a spout.

At northmodern he exhibited Belvedere and his Cork Helmet. Both showed that actually a designer has to take a step away and look at problems from a different viewpoint. Looking at old problems in the same way normally just comes up with the same solution.

When I first saw Vandeputte he was sitting 3 metres up looking very calm and relaxed above the phrenetic whorl of activity on the first day of the fair. He explained that he created the design because he likes to step away, or in this case step up, to somewhere calmer.

He showed me a series of photographs of him forming the cork helmet from a series of rings, cut from thick cork sheet, that were glued together and then sanded to shape. It is suspended from the ceiling by a cord and counterweight and is rather like the jousting helmet of a medieval knight. There are circular cuts out of the rim so that it lowers completely over the head and rests on your shoulders. The noise around drops to a gentle murmur - rather like putting your head under water in a swimming pool. I have to confess I felt slightly disturbed by trying the helmet ... slightly claustrophobic, in the gloom, and certainly rather vulnerable as suddenly I had no idea what was going on immediately around me.

snak, gren and gren light

Even if his name may sound Danish, Gunnar Søren Petersen was born in Bonn and trained and is now based in Berlin although he did also study at KADK in Copenhagen.

snak is a light dining table that can be carried around slung from the shoulder by a thin cord. The top is plastic that folds out with flaps then turned back under that make the surface rigid in use when it is supported on upturned wood tripods that clip into place.

The tripod shape is used again in gren, a modular system with plastic joints linking wood dowels that are used to form coat racks or screens that look organic - like a tree or a chemist’s diagram of a compound substance.

gren light has the same form as gren but the tripod junction is in porcelain with the electric flex of the pendant light running into a wooden stop on one arm and three light units set into the three down-ward and outward pointing branches of the porcelain unit. As with gren, the porcelain units can be linked together to make large complex forms.

copyright Gunnar Søren Petersen

This is more-clearly commercial industrial design than the works by Valentin or Pierre-Emmanuel but something more interesting emerged as I talked to Gunnar. We discussed Danish design aesthetics … I was curious on his take because he comes from the more clinically rational background of the German design school system, the heirs of the Bauhaus, but he had studied here in Copenhagen and I would say that that showed clearly in the softer more organic look of the light - particularly in the use of wood rather than, say, steel or plastic.

What we actually ended up talking about was how he had turned, shaped, and refined by handwork the precise form of each of the elements of the gren designs. What he said was that he knew every mm and every curve of the shapes and the moulds as he made sure that everything fitted together properly and looked absolutely right in the stages before it could go into production. There were, obviously, sketches and drawings for the system but, what appears to be the ultimate in industrial design, was, at least initially, hand crafted.

Some designs can and do go straight from the drawing table (or CAD screen) to the machine shop but, of course, I really like it when there is a hands-on approach to the design process and there is an important role for the maker or craftsman between conception and production. This is exactly what a designer like Hans Wegner did … making sure that something worked in terms of what he could do with the materials and resolving the aesthetics of the end product in a hand-crafted 3D stage ... the stage before expensive machine tools were set up in a factory or workshop. Yup 3D computer modelling and rendering on a screen has a place but still does not beat having something in my hands that I can twist and turn to see from all angles but also feel and touch.