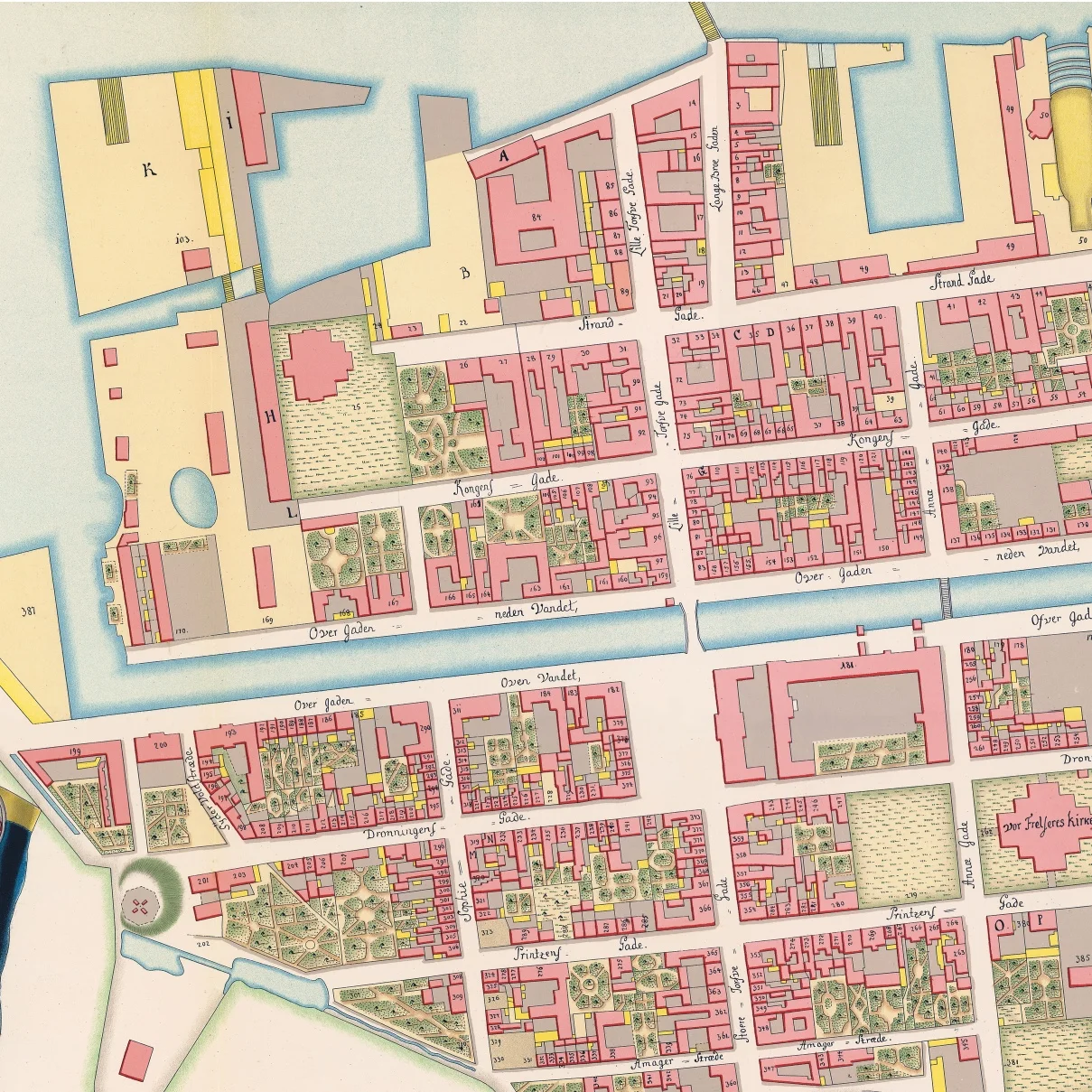

In Copenhagen, there is a clear change from the apartments buildings that were constructed in the late 19th century and early 20th century and the apartment buildings from the 1920s and 1930s.

In the 19th century each building was different from the next, often with relatively ornate doorways, carvings and complex mouldings for the street frontage and inside the arrangement of the apartments was often dictated by a narrow plot with existing buildings on either side that determined where and how windows to the back could be arranged. Even within a building, there were often differences between one floor and the next in both ceiling heights and in the quality of fittings.

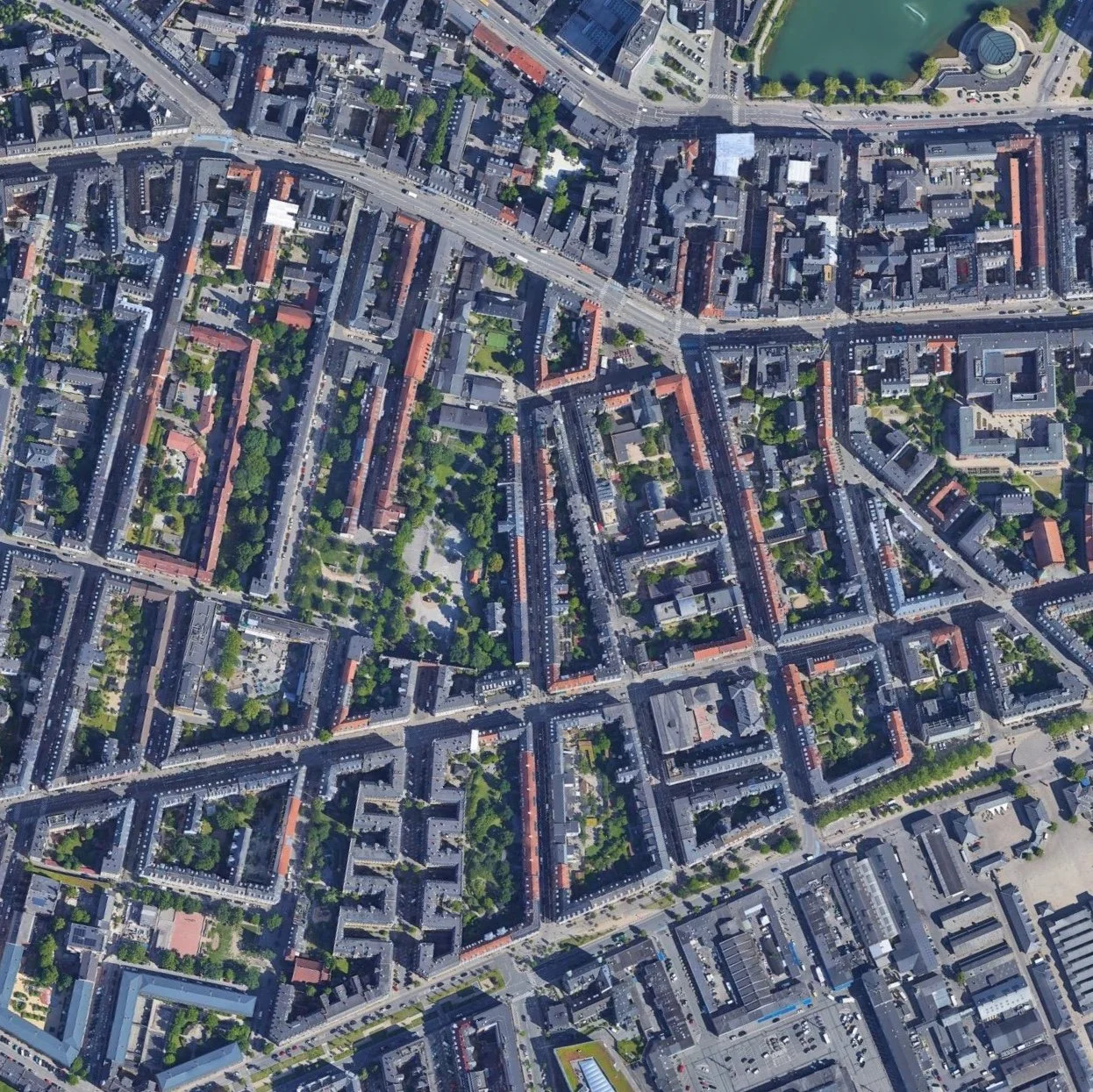

By the 1920s, plans of individual apartments became simpler and they were generally more compact and certainly more rational in their arrangement of the rooms and staircases. Because many of these new buildings were on new sites outside the old city, or if they were within the city a whole block could be cleared of old buildings, so there is generally a greater sense of uniformity within larger and larger buildings.

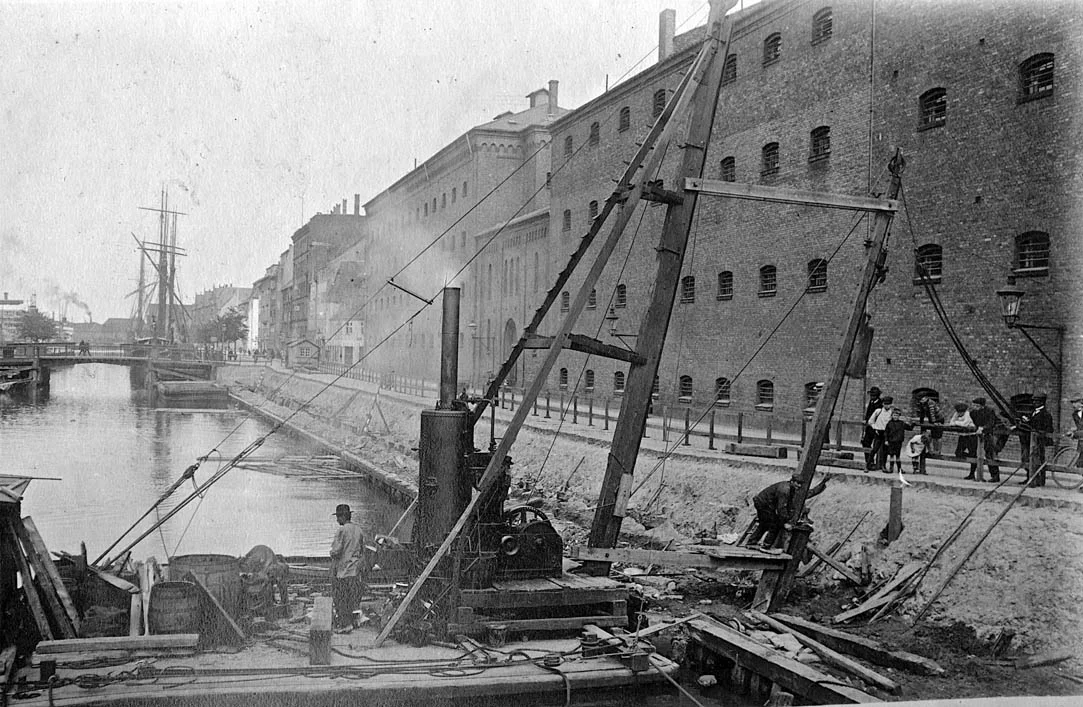

In part, this was because, in this period immediately after the First World War, there was a severe housing shortage and, to a considerable extent, the functionalism and the adoption of new building techniques was driven by a need to build as many apartments as possible and as quickly as possible.

Externally ornate decoration, such as pilasters or pediments or heavy stone or plaster window surrounds were omitted completely and the design, or rather, the articulation of the facade, depended on windows or balconies repeated regularly across the full width of the front.

By 1930 there might be some apartments with one bedroom and some with two and occasionally some apartments with three or more bedrooms - even within a single building - but usually fittings in every apartment and the style and arrangement of common areas within one building were the same.

Perhaps the most obvious change, between the buildings of the 1930s and developments constructed now is that, in apartments then, kitchens were relatively narrow and usually were to the rear of an apartment whereas now, in many modern apartments, the kitchen area is within the main sitting room or is even open to the sitting room or a sitting room, dining area and kitchen are a single open space.

In the last decade or so, some architects have tried to re-introduce more diversity in planning, to create more individual apartments within the same building - the most extreme example being the VM building by Plot where there are 40 different plans for apartments in the V building and 36 different plans in the M building - and there has been a return to having more prestigious apartments (so more expensive apartments) on one level. In the 19th century the best apartments were usually on the first or second floor - above the noise of the street but not up too many stairs. In the 1930s, if apartments were different in any way, it was probably only on the ground floor where they could be smaller as some of the area was taken up by the entrance lobby and lobbies and doorways to the courtyard. Now, of course, the best apartments are usually on the top floor if the building has a penthouse.

Changes in the way that people lived, at different social levels, can be seen clearly in the changes between 1870 and 1920. Of course there have been changes between 1920 and 2017 but many of those changes are architectural so structural or technical and to do with new materials but with little effect on the plan of the apartments or the changes are perhaps better described as improvements … so faster lifts, triple glazing, micro-wave ovens, dish washers and underfloor heating that all make life easier or more comfortable but do not in themselves actually indicate radical changes in the way people live … simply rising levels of prosperity.

Equally, major changes in people’s lives, so the ever increasing number of people living alone or the number of men staying at home to bring up children or even the rise and rise of computer technology in the home that would hardly be comprehensible to someone living in Copenhagen in 1930 have barely required any changes to the apartments people live in or the furniture they need and buy today.

Really, this is a long way of saying that we tend to see ourselves as living a very modern life - specifically a contemporary life by definition - but if people look for a starting point - a point of change in the way that most of us live - then the first truly modern housing and modern furniture - although many Danes would see the Classic period of modern design in the 1960s as the crucial point of change, in fact, the real context for what we call modern housing and for what we would recognise as modern design is back in the 1920s.

Through the late 1920s and the 1930s it was the technical methods of construction and the style of the buildings and, of course, some of the architectural features that changed. So there was the more and more frequent use of concrete for floor structures so, in many buildings, the outer walls were no longer load bearing. As a consequence, a distinct feature of this period is long horizontal runs of windows because long windows, with few or no intermediate vertical supports, are only possible when the outer wall is no longer important in taking the weight of the building above. By the 30s, many buildings have square bay windows for the living room or large balconies off the main living space - again partly to do with style or fashion but, for more rational reasons, again it was a fashion that was only possible because of those changes in the way that the building was constructed.

By 1930, decorative elements had been reduced or even omitted so there was relatively little or no decoration on either the exterior of apartment buildings or inside - so plain doors and simple door architraves became common - so that is doors and architraves without ornate mouldings. Most fittings were industrially produced so apartments had factory-made window frames that were often metal rather than wood and iron radiators and fittings in the kitchen that had been made away from the site. So this period also marked a clear change in the way that builders and artisans were employed with less on-site skilled labour. Carpenters were needed for the construction of the roof and floors, if they were not concrete, and of course brick layers had to work on the site but there were fewer joiners and, because ceilings were plain, there was no longer a need for highly-skilled plasterers who could run a moulded cornice or form decorative feature.

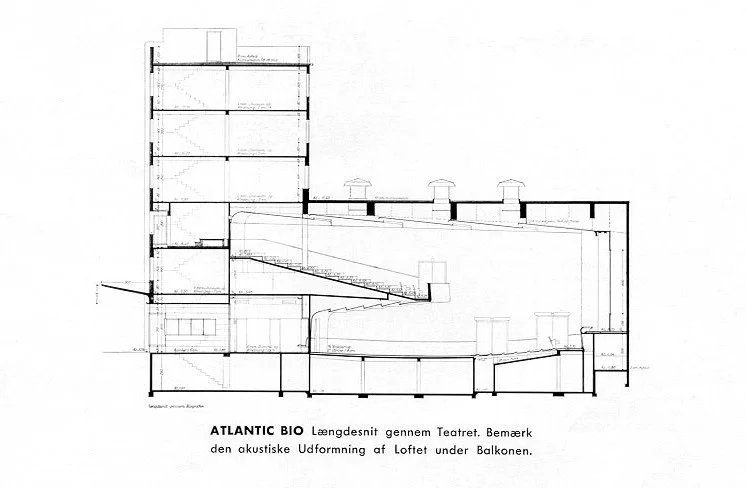

Staircases in the 30s were generally plain or restrained - so no great sweeps or curves of moulded handrails with shaped or turned balusters - but actually some architects did use quite expensive new materials like bakelite or chrome or brass - and the staircases often provided an opportunity to show off new engineering skills with cantilevered flights or thinly elegant landings and large walls of window that in some buildings rise up through several levels.

The standard arrangement in most apartment buildings was to have a main staircase reached by a lobby from the street with just two apartments at each level - one each side of each landing - but with secondary or back staircases that were usually reached by a door in the kitchen and gave access to the basement if there were service rooms like washing or drying rooms there and access to the courtyard for rubbish and so on.

In Copenhagen, the plan of the apartments - the way that rooms and staircases were arranged - developed through the first decades of the 20th century.

By the 1920s, there was usually one sitting room, a small kitchen and one or two bedrooms, in part depending on the size of the apartment, but even in Copenhagen now, many surprisingly-large apartments have just one bedroom.

In some buildings a distinct feature found in some apartments was to have wide door openings with double doors between the living room and the main bedroom, with the doorway in the centre of the wall rather than in the corner of the room. If there was a second bedroom it was smaller and often alongside the kitchen which meant that the way the rooms could be arranged was flexible.

Some contemporary plans show furniture so that it is obvious that in one flat the room adjoining the main sitting room was used as an extension of the living space but in another apartment, with the same overall plan and even though the two rooms were linked by wide double doors, the room was used as the main bedroom.

By the late 1920s perhaps the most important change was that many if not most apartments had a small private toilet or bathroom within the apartment - although some toilets had internal windows onto a staircase for ventilation. Earlier apartment buildings, particularly for working families, might have had toilets on stair landings that were shared between two families or more or the toilets were down in the courtyard and all families used a nearby public bath house.