The row houses in Lyngbyvejskvartet / Lingbyvej Quarter were built by the Workers Building Association between 1906 and 1929 for workers from Burmeister Wain and the architect was Christen Larsen who had replaced Frederik Boettger as architect to the association.

Lyngbyvej - the King's highway - is an important and historic road that runs out north from the city to Lyngby and from there on to the royal castle at Frederiksborg.

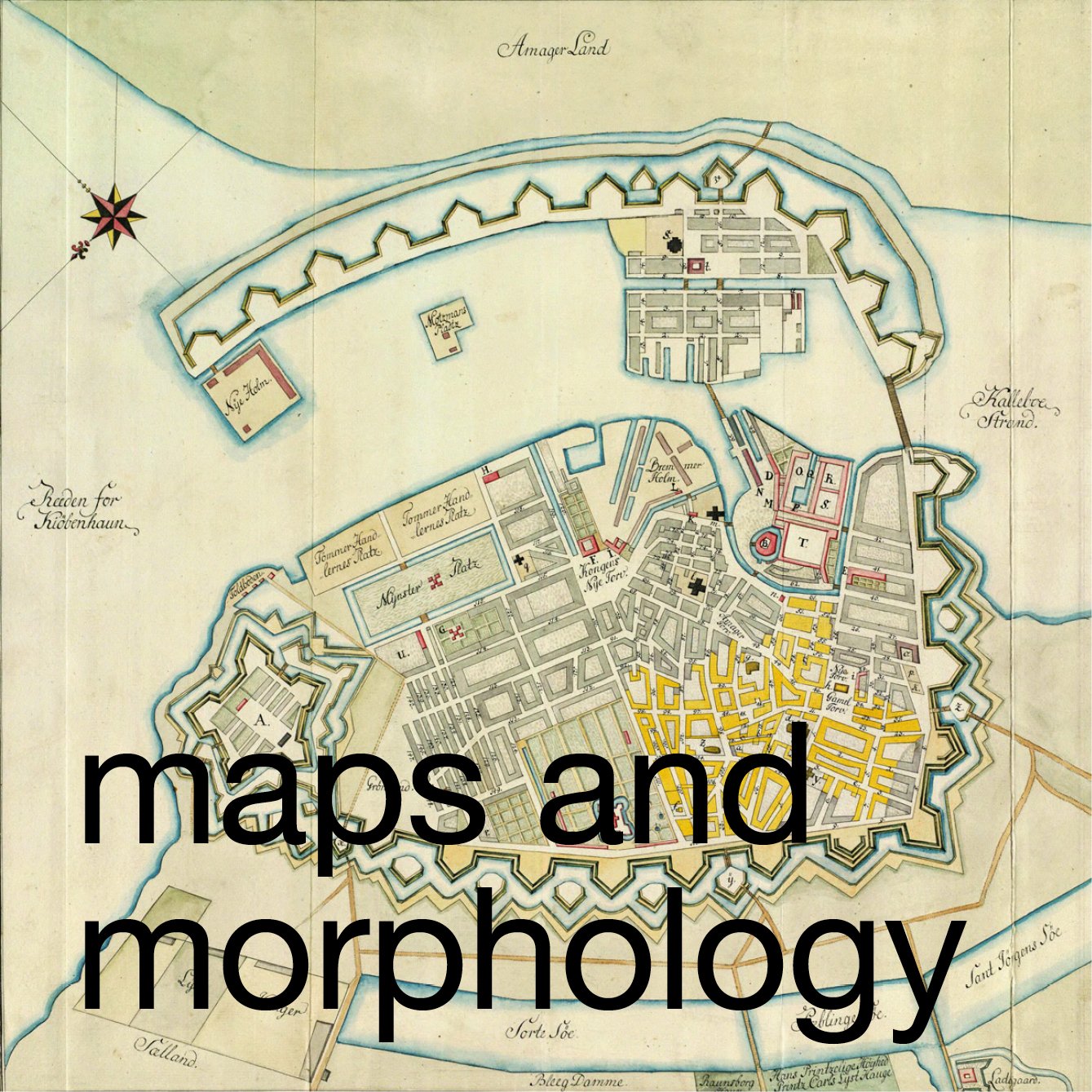

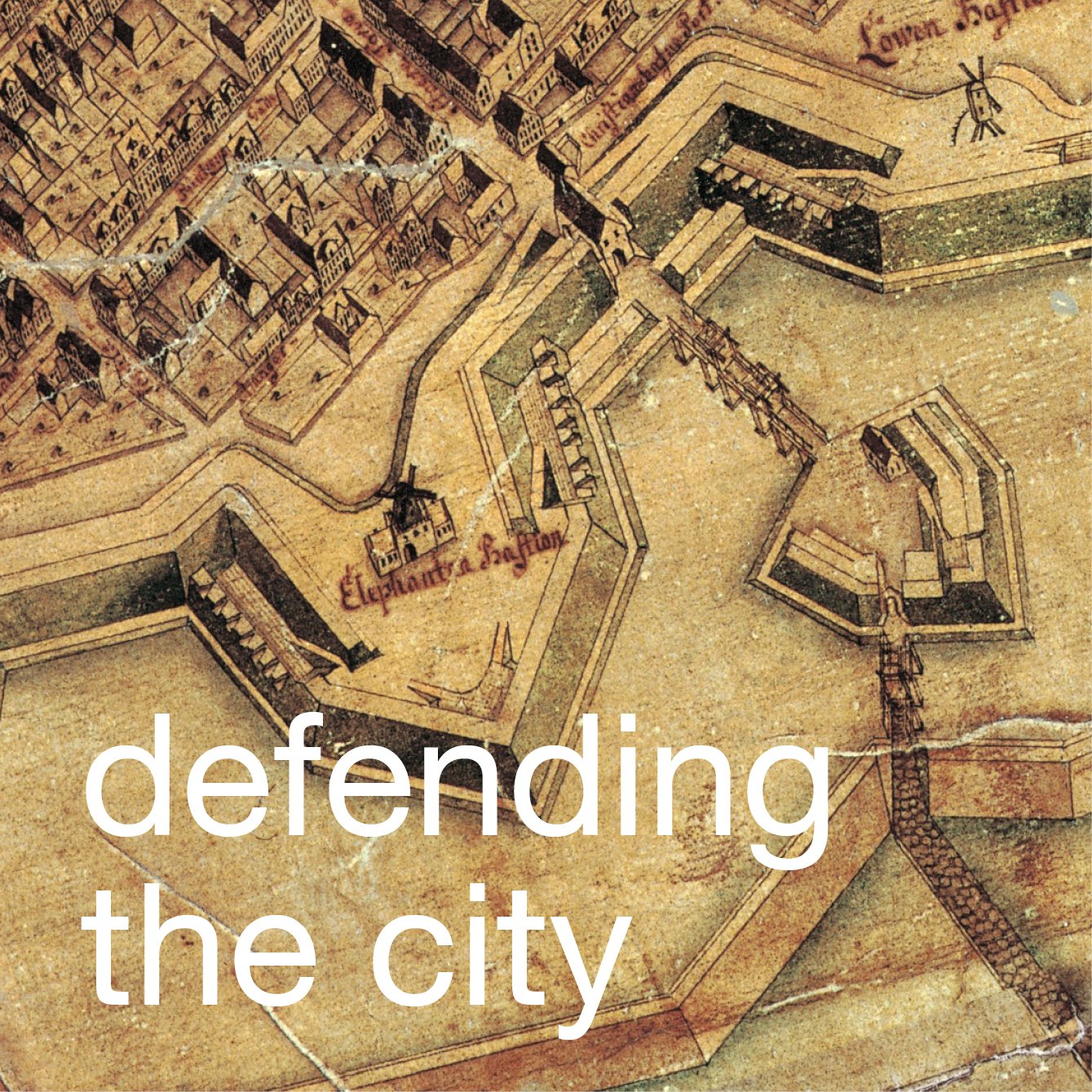

The housing is about 4 kilometres from the centre of Copenhagen. In a modern city this might not seem far but until the city defences were dismantled around 1870, the historic core of Copenhagen, on this side of the harbour, was confined to an area little more than a kilometre from the wharves to the north gate and around 1.5 kilometres across from the east gate to the west gate with remarkably little building outside the defences …. so this was quite a long way out of the centre for workers employed at the engineering works of Burmeister Wain on Christianshavn on the far side of the city or for men working at their ship yards at Refshaleøen.

This was a large plot of land … along Lyngbyvej it is 245 metres wide and it runs back to the west from Lingbyvej for just under 240 metres to Studsgaardsgade that is the west boundary. The north boundary is Borthigsgade and the south boundary Haraldsgade.

For the new houses, a spine road - F F Ulriks Gade - was laid out, running back from Lyngbyvej to Studsgaardsgade, with four cross streets running north south with H P Ørums Gade closest to and parallel with Lyngbyvej and then Engelstedsgade, Valdemar Holmes Gade and Rudolph Berghs Gade.

The plot is not rectangular - the south boundary, Haraldsgade, curves away to the south west - so each cross street from Lyngbyvej working west is progressively longer to the south. This makes a marked difference to the streets … so at the west end of the housing, H P Ørums Gade - the first cross street - is 100 metres long to the north of F F Ulriks Gade with ten houses on its west side, including larger houses at each end forming pavilions, and 140 metres long on the south side of the spine street with 13 houses with end pavilions. In contrast, at the far west end, south of FF Ulriks Gade, the row facing onto Studsgaardsgade is 240 metres long with 25 houses in the row with again larger houses or pavilions at each end.

Once completed there were 323 homes here arranged as twenty long rows or terraces running north south but with a further five short rows along the north side of the cross street - along the north side of F F Ulriks Gade - across the ends of the rows to the north and screening the long views down the gardens between the rows - and there were five similar blocks along Haraldsgade facing south.

The streets are now all on much the same level but historic drawings indicate that the land sloped down to the south and that some of the roads had to be raised and levelled above vaulted structures.

The names given to the roads are significant. Frederik Ferdinand Ulrik was a physician, who was a district and municipal doctor in Christianshavn … so he was working close to the engineering works. He was interested in the socialist movement in England and in Copenhagen he became a driving force behind the foundation of savings banks, public libraries and centres for adult education.

He gave a lecture about socialism and new workers’ political movements that was printed and posted up in the workshops at the engineering works of Burmeister Wain and soon after a meeting was held there, in November 1865, and the Workers Construction Association was formed the following day.

Most of the other streets here were named after doctors from the city hospitals.

The streets are wide, particularly F F Ukriks Gade, and all the houses had front gardens with low fences but space between rows at the back was surprisingly narrow, given the height of the houses, so the yards behind are relatively small.

Unfortunately, the houses along the main road - Lyngbyvej - lost their front gardens when the road was widened - presumably in the 1960s - and at that time the larger houses or pavilions at the ends of the two rows facing on to Lyngbyvej were altered and cut back.

These larger houses at the end of each row, particularly those grouped along F F Ulriks Gade, look more like a series of villas than like workers' housing.

The houses are said to have been built in fourteen phases over the twenty or so years it look to complete the estate and certainly there are different details in different streets including different designs for porches but also some slightly more interesting or eccentric details so the houses along one of the streets have nesting boxes for birds that are high up on the front of the houses and built with bricks that are set to project out from the main courses of brickwork.

With ornate balconies, an interesting mixture of red and pale brickwork and details in the brickwork like oval windows and courses of brick imitating rusticated pilasters and with a variety of ornate gables and dormers the style of the architecture is what is called national romantic.

There are drawings with plans and elevations for the housing in the national archive of Danmarks Kunstbibliotek and these can be studied on line.

Originally all the houses were divided with one apartment on each floor but subsequently many have been combined to form single family homes.

These are large houses that have basements that contained laundries, drying rooms and store rooms and there were separate apartments on the ground floor, first floor and at attic level. The roofs are steeply-pitched mansards so attic apartments have good head room and a similar floor area to the lower apartments.

What is striking is that the apartments all had their own toilet - not always the case even in large apartment buildings in the city in the 1920s. These toilets were mostly internal, so generally immediately inside the front door of the apartment, off the entrance lobby, so without windows or ventilation to the outside.

Apartments varied in size in the different rows and, particularly in the larger pavilions, some larger apartments were laid out so the toilet was against an outside wall so those could have windows for natural light and ventilation. None of the apartments had a bath.

In most of the houses in the rows there was a lobby area inside the front door and then a short flight of steps up to the main floor that was raised above street level by the service rooms in the half basement. Then the main staircase doubled back towards a landing at the front with a window at an intermediate floor level above the front door and then doubled back again up to the first floor in what is described in English architecture as a dog-leg staircase.

On F F Ulriks Gade - the main street running east west - the houses at each intersection have more elaborate architectural treatment and more prominent roofs and gables or large dormer windows so they look like pavilions but with the corners towards the intersection angled off and most had a door on that angle with the ground-floor space planned as a shop with a store room or back room to the shop and an apartment behind for the shop keeper. These houses also have a separate front door that gives access to the staircase up to the apartments above the shop and this door also provides private access to the shop keeper's apartment in addition to the access from the shop.

Although the apartments varied in size, all had, by modern standards, small kitchens. With one large bedroom, some had just one living room, labelled on the drawings as a day room, but most also had a dining room or a small second living room that for many families would have been used as a second bedroom.