is the growth of tourism in the city a threat?

/In a number of posts on this blog, I have written that I feel that the rapid rise in the number of tourists visiting Copenhagen and the construction of a large number of new and very large hotels over the last decade could be a serious threat to the character of the city and one that is barely discussed by politicians.

Arguments for the growth of the tourist industry in Copenhagen that are usually put forward include the creation of jobs, the suggestion that the tourist industry attracts inward investment and that money spent by tourists in the city, in shops and at tourist destinations, is crucial for the local economy.

Arguments against what appears to be uncontrolled growth, is that the huge number of tourists with, of course, the astounding number of passengers from the cruise ships that come to the harbour - just under a million in 2019 in the year before the pandemic - are swamping Copenhagen and changing the character of the city. There is a certain irony in this because the visitors, by their sheer numbers, are damaging and changing what they have come to see.

Jobs are certainly created by the hotels but how many of those jobs are short term rather than long-term careers and where do hotel workers live? In the big hotels in the past, chamber maids and porters might well have lived in the hotel, in garrets and dormitories. That's hardly a positive thing but do short-term workers in the modern hotel industry add to serious problems caused by the shortage of affordable housing in the city?

Those jobs fuelled by tourism are not just those working directly for hotels and the tourism service industry such as guides but there are also jobs in supplying food, cleaning and servicing the hotels and restaurants and, of course, in general retail - many of the stores in the city have departments that are deliberately geared up to dealing with foreign visitors. Popular destinations for tourists including the city museums and galleries now depend on tourists coming through the doors and not only paying for entrance but spending in cafes or restaurants and souvenir shops. The argument then is that tourism subsidises facilities for local people that could not be supported on local spending alone.

When Coronavirus-19 struck the city, museums and galleries had to close and even when the lockdown was eased, the number of visitors has been slow to recover.

Designmuseum Danmark had serious financial problems as a consequence and they revealed that 90% of their income came from tourists. However, that should not be an argument for returning as quickly as possible to the pre pandemic numbers of tourists but a warning that the government and the city have left the museum vulnerable with a funding model that may well continue to be unreliable if coronavirus returns or if people are concerned about the possible and ongoing dangers of travel.

The tourist sector generates work for architects, engineers and interior designers who build and refurbish hotels and restaurants and there is an argument for soft-power influence for Danish design and manufacturing with tourists who visit hotels and design stores and see and use furniture and so on that they admire and they are then more likely to buy Danish designs when they return home.

Are there statistics to back this up?

There is certainly a strong market in high-quality Danish furniture that is purchased here in antique shops and second-hand stores and flea markets and then exported by the container load but that is not directly a byproduct of tourism.

Even foreign investment might not always be positive .... investment money coming into the country may well be offset by profits going out and many investors may well be blind to local issues and not susceptible to local pressure however well founded.

Even the amount of money spent by tourists may not actually be as much as assumed - how many passengers from a cruise ship buy little more than ice cream and a post card - and is there also a sort of escalator here? Successful tourist shops or successful restaurants aimed at visitors rather than local people can be profitable and then attract more businesses to jump on the band wagon. In recent criticism of the state of the Walking Street, local people commented that is now full of shops that sell tourist tat and that they avoided the area as much as possible.

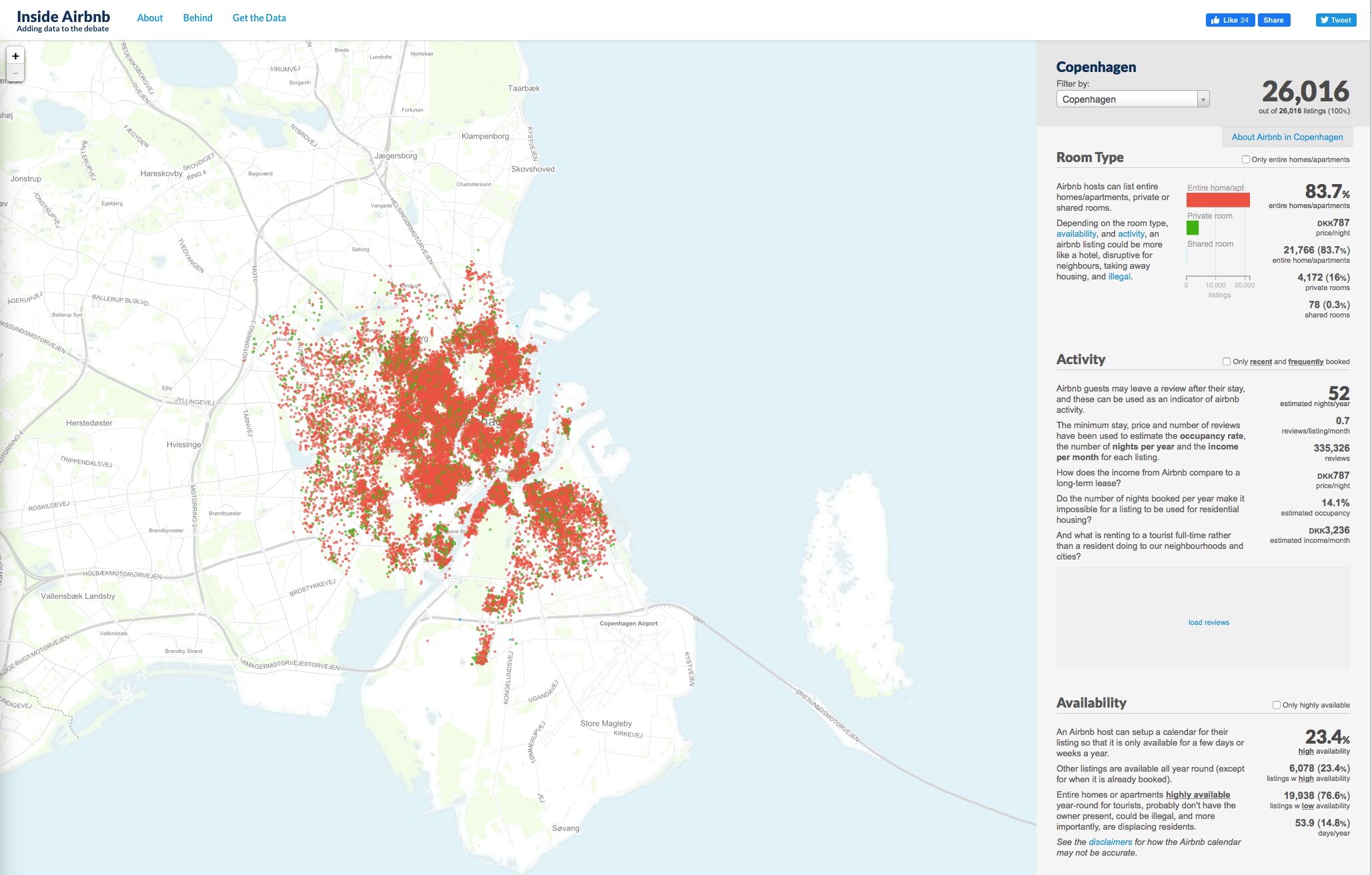

Airbnb is a specific facet of tourism that has to be addressed at a political and planning level and stricter legal controls have to be introduced. The initial concept - with people using a spare bedroom to earn a little extra income and gain from entertaining visitors and proudly showing them their city - is fine and if people have to or want to move abroad for a short period and need to retain their home but have it work for them then Airbnb is one possible solution. The problem is when properties are bought to let as a portfolio investment because that is removing far too many homes from the normal rental market. Looking at maps of the distribution of Airbnb properties across the city then there are over 20,000 complete properties to let - rather than single rooms. If those homes were returned to the rental market then that would be close to the total of new homes that will be built on Lynetteholm - the contentious new island that will be constructed across the entrance to the harbour that is being promoted as a place to build housing for 35,000 people. One possible solution for the Airbnb problem would be to levy an additional tax based on profit that would be ring fenced for funding the construction of more social housing.

the distribution of Airbnb properties across the city

Copenhagen has always been a city that welcomed visitors but an important part of the appeal of the city is that so many people actually live in the historic centre. Large new hotels have taken over buildings or plots of land that could have been used for student accommodation or for social housing. There is a danger that if the number of tourists grows without more controls then the city will change from a place where people live who welcome visitors to a city that is a tourist destination where people live.