climate change and rising sea levels

/

If there is a sudden rain storm In Copenhagen and, within an hour, streets are flooded and businesses are closed and transport is disrupted, then the consequences from climate change seem obvious and imminent. Problems are here and are now so, for politicians, planners, voters and tax payers, the need to act and act now is easy to understand.

But rising sea levels are more difficult.

For a start, the time scale is longer. People still talk about dealing with once-in-a-hundred-year storms … perversely trying to persuade themselves that means it will not happen for a hundred years when a catastrophic storm tomorrow could still, strictly, be once in a hundred years if it's then 99 years until the next one.

Statistics and the data seem much less certain for the rise in sea levels but how can we expect scientists to be any more precise with predictions when these changes are on such an enormous scale and there are so many variables - not least when it comes to calculating a tipping point as sea ice or glaciers melt?

But for Denmark, these calculations and planning now for works for mitigation are crucial.

On one side of the weighing scales, for policy makers and planners, are some positives: Denmark is a relatively small and relatively prosperous country with a strong history of major and successful engineering projects and with a population that still appreciates and understands the role of the state in major interventions for general gains. But, on the other side of those scales, Denmark is a low-lying country with an astonishing number of islands and a coast line that, as a consequence, is said to be about 7,300 kilometres in length. Is it a case of too much to do and too little time?

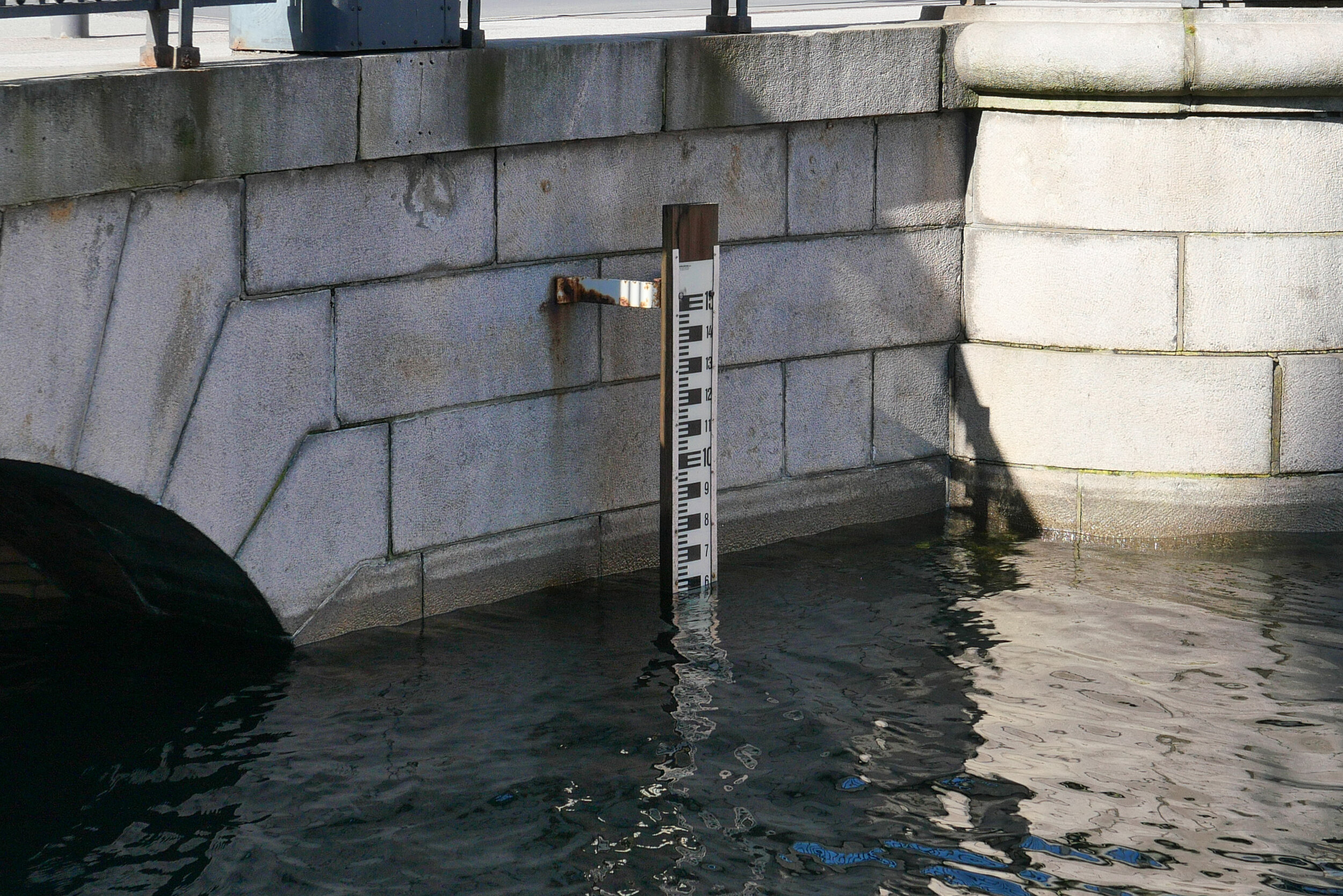

Living now on Nyhavn I'm very aware of the levels of the water in the harbour as the tide rises and falls each day. It might not be as dramatic or by as much as on the west coast - where settlements face out to the North Sea and its weather - but still the level of the water in the harbour rises by as much as a metre from the lowest to the highest level through each day. There is a fixed measure on the bridge across the middle of the harbour that I can see from my desk … or, to be completely honest, there is a height marker I can see from my desk if I stand up …. and I can also hear when the tour boats stop just before the bridge to drop off and pick up passengers if the tide is too high for the boats to get under the bridge to reach the ticket office and landing stage at the top of the harbour.

The quayside here is just 1.5 metres above the level of the sea water at high tide …. so, to put it the other way round, the sea is just 1.5 metres below my front door.

The highest tidal surge out in the sound - sea water driven by winds or storms - was apparently three metres in 1872 although there seems to be no record of floods and damage in the city that year as a consequence. Complete official records date back only to 1890.

There was a surge of 1.57 metres in 1921 and the highest surge of sea water from a storm recently was on 19 January 2007 when the water level rose by 1.31 metres. I've looked at back copies of Politken for that weekend but, curiously, there seem to be no reports of flooding or damage in the city with just one report about the harbour that weekend that has a photograph of a huge number of bikes that had been hoiked out of the canal around Christiansborg as part of a clean-up campaign.

But then add the height of a possible storm surge to the higher level of the sea because of global warming and melting of polar and Greenland ice and you can see why the city has to make major decisions now about what has to be done.

Calculations have suggested that, between now and 2050, sea level in the sound will rise between 10 centimetres and 30 centimetres and by the end of the century - so only 80 years away - the rise in sea level here will be between 20 centimetres and 1.6 metres with a 5% chance the rise will be over 2 metres. The median figure for the rise in sea level for Copenhagen is 70 centimetres and that could mean water lapping over the quay at high tide.

The only thing that is certain, is that I won't be here eighty years from now but, in a worst-case scenario, the sea will be at the front door of this building and that is without worrying about storms.

The whole of Christianshavn was built up out of the sea in the 17th century and looking at historic maps it is clear that the outer part of Nyhavn was built out way beyond the line of the beach.

I have read somewhere that the crown sold off areas of the sea bed and it was up to new owners to drive in wooden piles and fill in and create a plot for their buildings. Whether or not that is true, I wonder how much rising water levels will effect foundations. There is remarkably little visual evidence for subsidence but what will happen as the water table rises? And, more important, whatever work is considered to protect the city from flooding, major engineering interventions will change, and change permanently, the character of the inner harbour and the beaches and low-lying land of Amager - the island immediately to the south of the city.

Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.

Last year - in September 2019 - the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published their Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.

Produced by more than 100 climate and marine scientists from 36 countries, this report assesses how global warming is having an impact on sea levels as sea ice melts and uses clear research data to calculate the potential extent of change and the rate of change.

Through the 20th century, sea levels rose by 15 centimetres (6 inches) but as global warming is causing ice in glaciers and in the Arctic and Antarctic sea to melt at twice that rate then calculations indicate that by the end of the century, so by 2100, sea levels will rise by an additional 10 centimetres so between 61 centimetres and 1.1 metres and if the Arctic ice sheets melt faster than current predictions suggest, then, by 2100, sea levels could rise by 2 metres.

Small glaciers are expected to lose more than 80% of current ice mass and that would have a severe impact on supplies of drinking water and consistent supplies of water to rivers for irrigation. With flooding of coastal areas and the impact on coastal cities and on densely populated delta areas then changes to sea level will dramatically reshape "all aspects of society."

The report can be read on line and the separate sections downloaded.

these are:

Summary for Policymakers

Technical Summary

Framing and Context of the report

High Mountain Areas

Polar Regions

Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities

Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems and Dependent Communities

Extreme, Abrupt Changes and Managing Risks

Integrative Cross-Chapter Box on Low-lying Islands and Coasts