Ét Danmark uden parallelsamfund / One Denmark without a parallel society

/This was a difficult post to write because it is about sensitive political and social issues but the subject is important and not least because there very specific implications for planning and housing in Denmark that will influence future policies for planning and should have a much wider relevance and for many if not most countries.

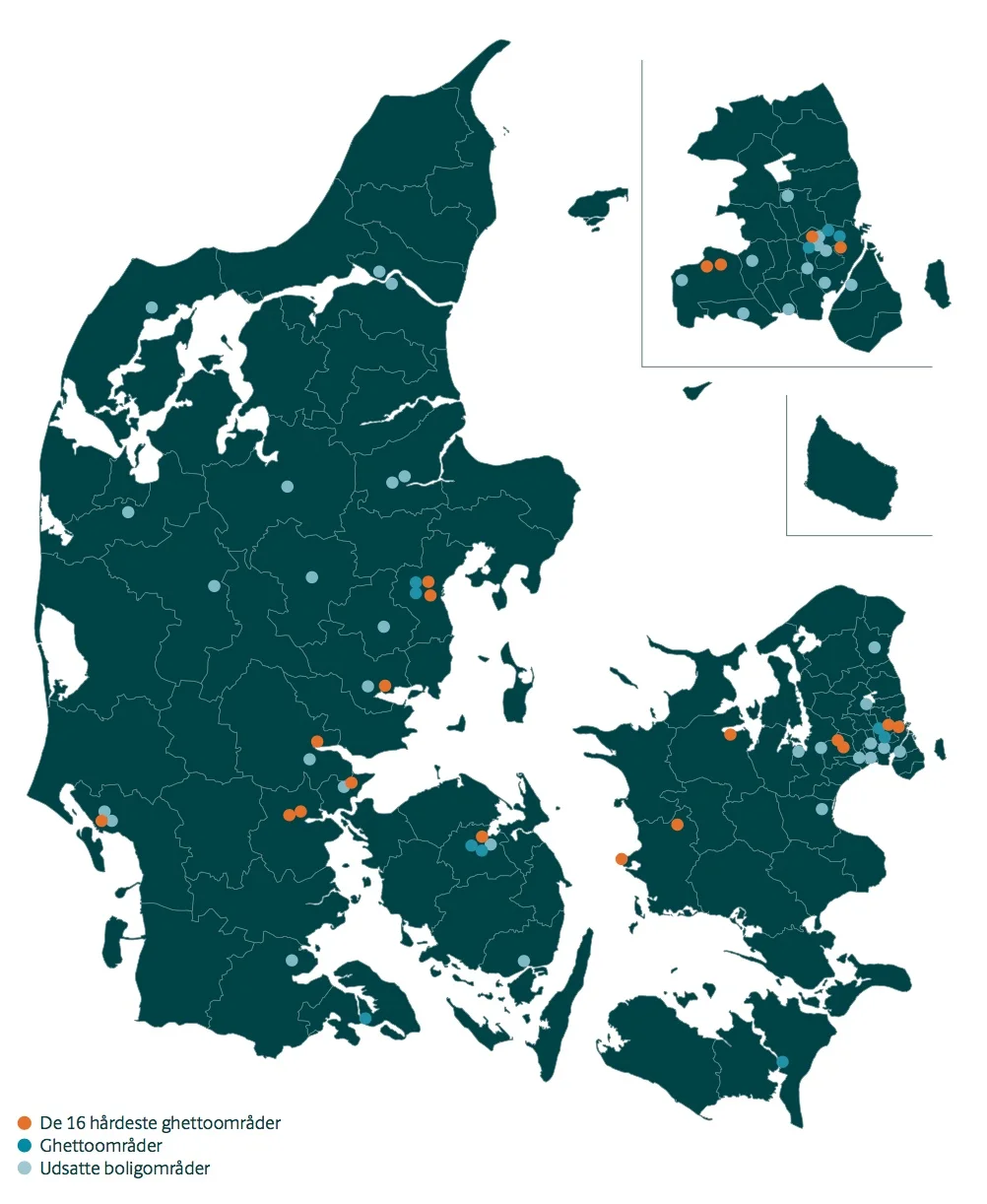

In the New Year the government published a report - Ét Danmark uden parallelsamfund / One Denmark without a parallel society - that sets out a policy to tackle problems in some urban areas in Denmark that will now be defined officially as ghettoes.

My immediate image of a ghetto - the picture conjured up by that word - is of crowded and poorly-built and or badly-kept buildings that are occupied by people kept there by poverty, isolated from wider society and from wealthier neighbourhoods, often nearby - so slum housing - so people, for different reasons, trapped and living with high levels of deprivation.

Here, obviously, I have to admit that I have had a relatively privileged and very middle-class life growing up in a very beautiful university town and then in well-designed modern housing in a new town. When I went away to university I went to Manchester to study art history - you can hardly get more middle class - and I loved the grandeur of the Victorian city and lived initially in what had been, in the 19th century, a private gated street of large villas. But that was just two blocks away from Moss Side … then defined officially as being the worst slums in Europe. Worse than Naples or Marseilles or Glasgow. Recently I came across some images of the slums in Moss Side and other parts of Manchester taken by Nick Hedges - a photo journalist - at exactly the time I lived nearby and I was truly shocked because it made me realise that time has blunted my memory of just how grim that area was and my memory had blotted out what was the reality of life for many people who lived there less than fifty years ago.

Since then I have driven through Soweto, seen Baltimore and travelled through much of South America so I am not naïve about the reality of poverty and deprivation - just naïve about how you deal with it.

I feel strongly that anyone and everyone visiting New York should go to the Tenement Museum and people should look at photographs of slum housing in London in the 1930s and in the 1950s and 1960s for a realistic context to understand just how recently that sort of housing was a reality in what are now very wealthy cities. There is a tendency in the affluent west to be blind to just how recently that sort of poverty and that sort of housing existed in their own countries.

In Denmark the definition, by the current government, of specific housing or distinct areas as ghettoes does not, in fact, stem from or define that extreme sort of housing but is about what problems that have developed as people migrate to Denmark but want, as most humans do, to be with people who have a common background and often a common language. Many Danes are aware that, in the worst situations, this can lead to isolation of communities and then on to a cycle of relative poverty and problems with education and employment that can trap people. And when people are trapped they do not benefit, as much as they should, from being an integrated part of Danish society. There is a growing concern that being isolated really does increase social problems - particularly for boys and young adults, and their membership of gangs - and it is that isolation that is described as living in a parallel society.

It is difficult because visitors - and presumably many migrants - coming to Denmark see affluence and see tolerance and see a freedom of life with enviable choices and then make the assumption that that was and is an easily achieved privilege. Actually, it has to be remembered that for older Danes, many can remember the slum housing in Vesterbro - as bad as anything in Manchester - or the slums that were cleared away in the 1950s from the area around Borgergade - not far north of the royal palace - and they know that their high quality of life now has been achieved through social and political changes and not simply dished out. I cannot recommend enough a visit to Arbejdermuseet - the Workers' Museum in Rømersgade - to find out more about working conditions and living conditions for many families in Copenhagen through the 19th and 20th centuries.

Of course the problem for migrants, in search of a better life but finding themselves isolated and trapped, is not just a problem in Scandinavia or for the affluent west but is a global problem and not just about the equitable distribution of opportunity and resources but how you can expect people to be taunted by affluence through advertising and merchandise sold to them, but remain content with what they do or, more often, don’t have.

And, of course, the problems tend to be seen as the consequence of migration from one country or one continent to another but is just as relevant with mass movements of people from rural to urban areas within a single country. This is really about managing expectations and managing numbers.

In Denmark, twenty-two initiatives have been set out by the government for urban areas that have problems seen to come from people living in a community that, for many different reasons, are isolated and parallel communities. Funding will now be available for demolishing some housing and for improving some areas but also there will be measures targeted at education with a focus on vulnerable children. Sixteen ‘ghettoes’ have been identified and substantial amounts of funding have been allocated to make the changes set out in the report.

Much of the programme to deal with these ghettoes is about social housing and about the stock of older housing - some from the 1920s and 1930s but also from the post-war period - so housing that would not be built in that way now … and it's about learning lessons and about trying to prevent more problems down the line through intervention now through education and through focused urban planning.