On either side of the reunification monument, there are elaborate stone drinking-water fountains.

Again the style is taken from classical architecture. For each there is a tall stone podium that is square in plan with a moulded base and cap and on the top are giant open bronze shells that are, presumably, a symbol of wisdom.

The front of these drinking fountains have very bold architectural treatment with squat but finely-fluted applied half column broken by a bold square block across the lower part in a form usually called rustication but here on a giant scale, and those blocks hold a fine bronze shell that drops water down into a round stone basin at the base.

Both drinking fountains are set at an angle, facing inwards towards the apex of the triangle and they frame the two paths on either side of the memorial that lead into the park, There are low retaining walls curving out to the buildings on either side to create a symmetrical arrangement that closes the open public space of the triangle and marks the transition to the open space and trees of the park beyond.

Around the curve behind the monument are nine lights - low or rather not tall and each with a bronze stanchion and a simple pearl-like globe light.

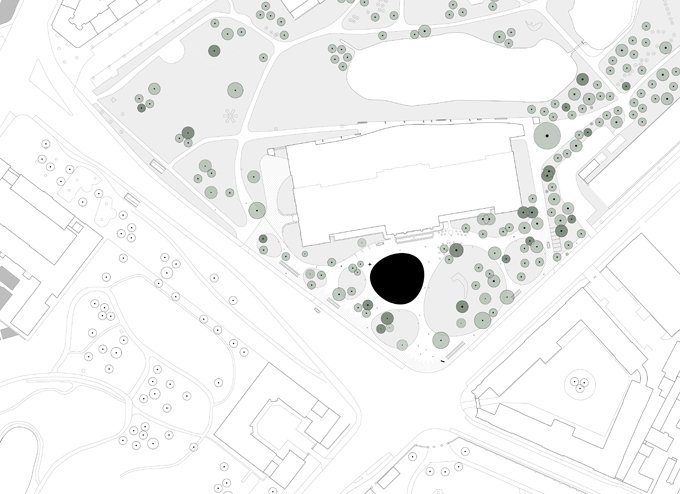

There is a strong underlying geometry to the design that is not immediately obvious when you are walking through the space, in part because it is on such a large scale, but it gives the entrancea rational and clever underlying structure that creates a clear order to the space and to the procession from the urban space of Trianglen through to the open space of the grass area of the park. This should be read as if it is movement through a series of spaces, comparable to moving through a series of rooms and certainly not like moving through a natural landscape.

Also, the design shows how an architect or designer can pull together existing angles of roads and buildings - determined by topography or street alignments - and can direct the way in which people will move through the spaces but the plan also creates interesting and dynamic diagonal views that you would not get with a simple progress along a straight axis.

The statue and its plinth are set in a circle of cobbles but that is set within a larger but less obvious circle of gravel that is itself framed by a border of cobbles. That larger circles overlaps a large stadion on the axis that is set out with a gravel path beyond but the overlap is masked by a low hedge following the back curve of the circle of the statue.

A stadion is simply a long rectangle with semi circles across each end so there are long straight sides and curved ends so not an oval. The form is found most obviously as the shape of a running track so here it is a reference to the use of the public space of the park for sport. Seen from above, the statue is at the centre of its circle but also on the long axis of the stadion and actually sits across the path - so if you run around the stadion, as if it was a running track, then you have to divert around the statue.

At the far end of the stadion, towards the open park, the gravel path expands out into a curve that cuts into the main shape of the stadion. It mirrors the entrance end, but without the full circle of the setting of the statue, and has a set of curved stone benches where you can sit and look out across the park.

It is fascinating to see how a city or a country has seen itself at various points in history by looking at how a style of architecture is used to establish or reflect or reinforce a common sense of self identity.

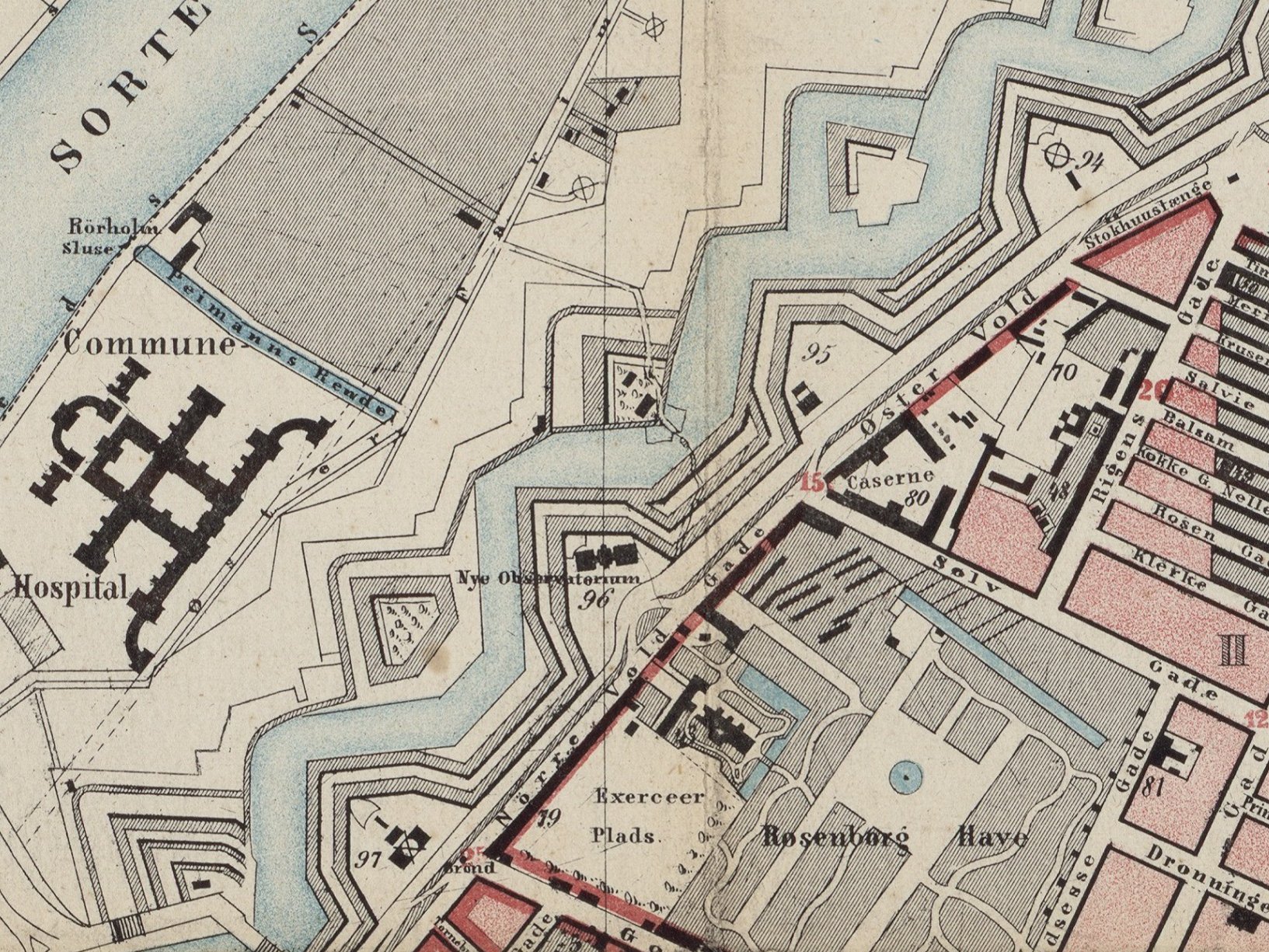

Following the war of 1864, and the loss of much of Jylland - the south part of Jutland that was annexed by Germany - Denmark spent the last decades of the 19th century reassessing and then rebuilding and then moving forward.

Initially the style adopted for much of the new architecture at the end of the 19th century was inspired by the rebuilding of Paris in the period of Hausmann after the revolution of 1848 - so many of the new apartment buildings from that period in Copenhagen imitate pale stone ashlar, have large sash windows, mansard roofs and ornate wrought-iron balconies.

By 1900, and with the growing prosperity of the city based on trade, many of the new office building along Hans Christian Boulevard and even the new city hall itself looked to that other great trading nation of city states for inspiration so to Italy and to Florence and Sienna and to banks and civic buildings in those cities as a source of architectural forms and decorative motifs.

As the prosperity and success of the Copenhagen renaissance became more tangible, there was a growing sense of pride in architecture and achievements that were more specifically Danish or Scandinavian so architects and sculptors looked for inspiration to the buildings of Christian IV in the first half of the 17th century so towers and turrets and gables in the style of Frederiksborg or Kronborg, but dating from around 1900, can be seen all over the city.

But the entrance to the park and many of the new public buildings around the park are different in style again. Here, through the 1920s and 1930s, the inspiration is classical architecture - not Renaissance Italy but ancient Greece and Rome - and of course that seems appropriate for buildings like a swimming pool and the stadium so it appears that there was a new worship of fitness and the male body - or at least a sanitised view of what Hellenic sport was all about - and with it came a need to express or imply heroism and nationalism … and, in terms of style, a different form of nationalism to the power and wealth shown by the buildings of Børsen - the Royal Exchange - or Rosenborg or Kronborg.

This gets perilously close to the architecture of nationalism of the right in Italy or Germany in the 1920s and 1930s but maybe that slight uneasiness we can feel, when we see architecture like this, comes because we are looking back but of course, these architects could only look for styles of architecture that they felt were appropriate without our awareness of the dark consequences of some forms of nationalism some ten or twenty years later. The monument to the motherland at the entrance to Fælled Park - to mark the return of South Jutland to Denmark - implies a quiet national pride … it's certainly not bombastic, not vainglorious and not triumphalist because that's not the Danish way.

note:

Several architects produced designs for this entrance after the park was established.

Kaj Gottlob designed two large, U-shaped buildings on either side that were to be set at an angle determined by each of the main roads (so before the post office was built) with open courtyards to the back and with forward-facing facades and between them a tall and elaborate loggia with pairs of columns, one behind the other, on the side towards the triangle and matching pairs on the side towards the park and people entering the park would have walked across - not along - the loggia.

In 1917 Vilhelm Lauritzen designed a similar pair of large buildings to flank the entrance but he designed between them an arcade with five giant arches rather like a Roman viaduct.

In complete contrast, in 1918, Peder Pedersen designed a low geometric fence across the back of the triangle with a pair of pavilions on either side of the entrance, gate lodges between the triangle and the park so a rather rustic version of the fence and pavilions around the King's Garden in the city. The drawing by Pedersen in the national archive is also interesting because his plan shows the tram tracks and the triangle in front of the entrance had a large tram stop on the Øster Allé side and a turning circle for the trams in part across the triangle.