Blågård means blue court or blue farm and was the name of a large single-storey house with stables and outbuildings that was built here in 1706 by Prince Charles of Denmark. The name is thought to have come from the blue glazed tiles that covered the roof.

At that time there were very few houses immediately outside the city walls, in the area between the city wall and the lakes, left clear deliberately so there was no cover for an army attacking the city from the land side.

In the 18th century, leaving the city by the north gate, close to the position of Nørreport railway station now, the traveller would have crossed between the lakes that were then wider and more irregular in outline. The house was beyond the lakes, on the left side of the road, not facing the road but facing back towards the lakes with formal gardens between the house and the lake and further gardens south-west of the house roughly where Blågårds Plads is now.

A detail of the map of the city in 1779 shows the north gate at the bottom centre with the defensive walls and outer ditch and to the right the recognisable outline of Rosenborg and its gardens. The bridge over the lake has a gap indicating a draw bridge and the main road north follows the line of the present Nørrebrogade.

The buildings of Blågård are in the centre towards the top, on the left of the road, with formal gardens and two square ponds towards the lake and a semi-circular terrace and then presumably further gardens (the site of the present square) running across to a stream or ditch, that was a boundary following what is now Åboulevard which still has that distinctive curve.

In 1780 the buildings, by then enclosing a courtyard, were converted to a clothing factory and then in 1791 the property became a teacher training institute. It was used as a hospital during the bombardment of Copenhagen by the English in 1807 and then in 1828 it became Nørrebro’s first theatre. The house was destroyed by a fire in 1833 and it was after that that the area became more densely built over.

Even as late as the 1850s there were very few buildings along the shore of the lake or along the river that formed the boundary between this land and what is now Åboulevard then called Aavein Aagade on one side of the river and Ladegaards Veien on the far side.

A map of 1860 shows that by then the much more urban grid of roads had been laid out although there were detached houses along the lake side of Blaagaards Hoved Gd (Blågårds Gade) set back from the road with front gardens rather than the continuous line of apartment blocks now. Building work and the infill of empty or garden plots was then rapid and by the time of the map of 1886 the area was densely covered with buildings.

By the beginning of the 20th century this was one of the poorest working-class areas of the city so there had been quite a transformation from the royal manor house and gardens 200 years earlier.

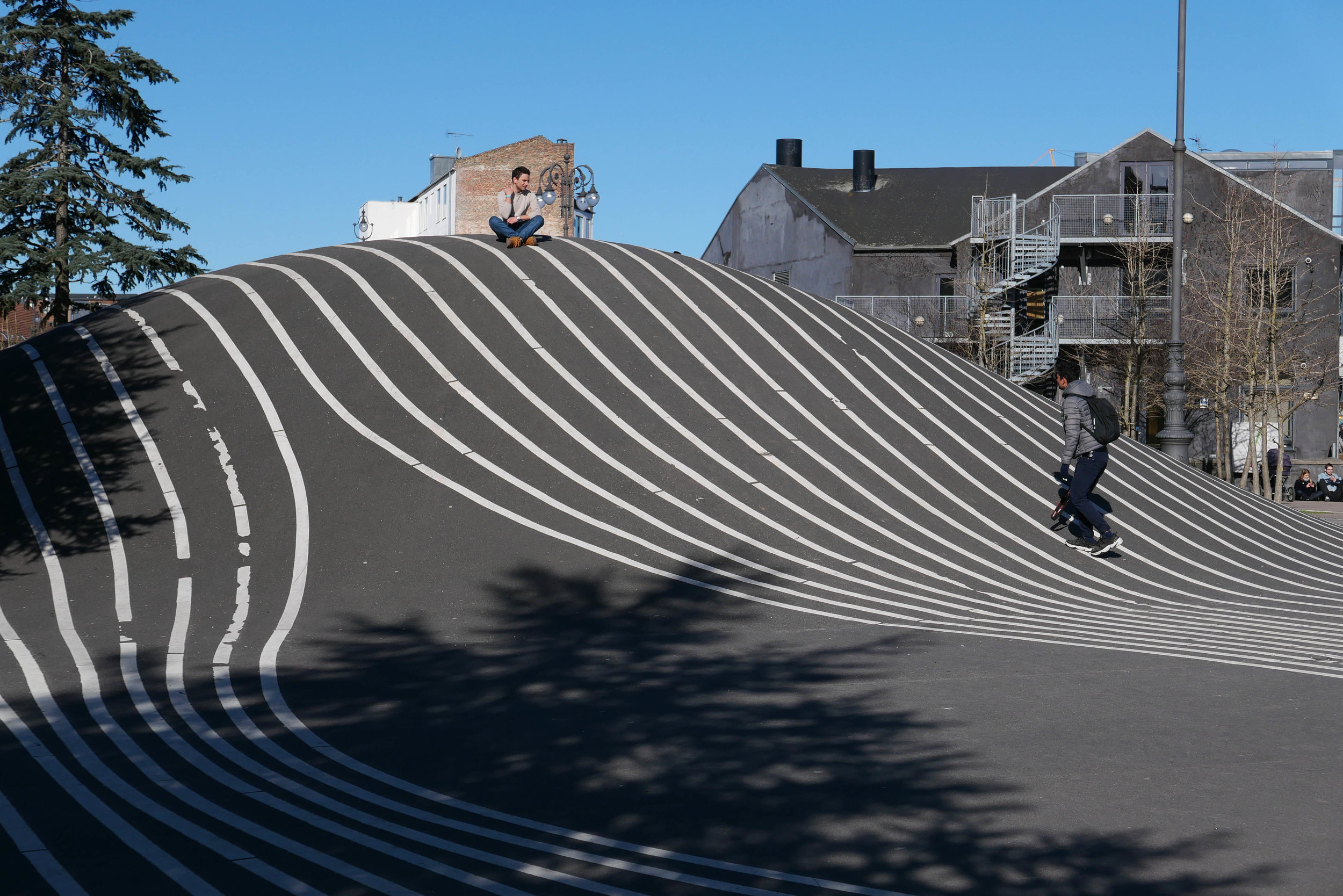

The creation of Blågårds Plads around 1912 was actually a major decision in terms of city planning because a whole block of commercial buildings were demolished to create the large open space. The square is open to Blågårdsgade that forms the south-east side of the square and the square runs back just over 100 metres from the street and is just under 70 metres wide. On the north-east side there is a small secondary open space 11 metres wise and extending back 23 metres to the entrance front of the church that is now a concert hall.

The centre of the main square is lower and surrounded by a parapet wall marking an area approximately 47 metres long and 28 metres. The wall and the steps down to the lower area are decorated with an amazing set of stone figures of adults and children by the Danish sculptor Kai Nielsen.

Presumably the demolition of houses and industrial buildings to create an open space was controversial when the square was laid out but there were certainly very strong protests in the late 1970s when properties were cleared and the library on the side opposite the church and new apartments and courtyards at the back of the square were built. Criticism of the scheme were, apparently, so strong at the time that the city authorities resolved to make public consultations a more significant stage of the planning process for any future redevelopment.

Why so much history on a site about modern architecture and modern design?

Without doubt people like history … otherwise why so many costume dramas on films or TV … and it is important to have a sense of place and a sense of context if it helps people avoid a sense of alienation or isolation.

Even if we live for the present and focus on the future, the roads we walk up and down and the buildings we live in and use all have a context. Tangible things like topography, field boundaries, plot boundaries and older buildings that have to be kept for some reason and less clear influences such as politics or the economic situation all have an effect on what can be built or rebuilt.

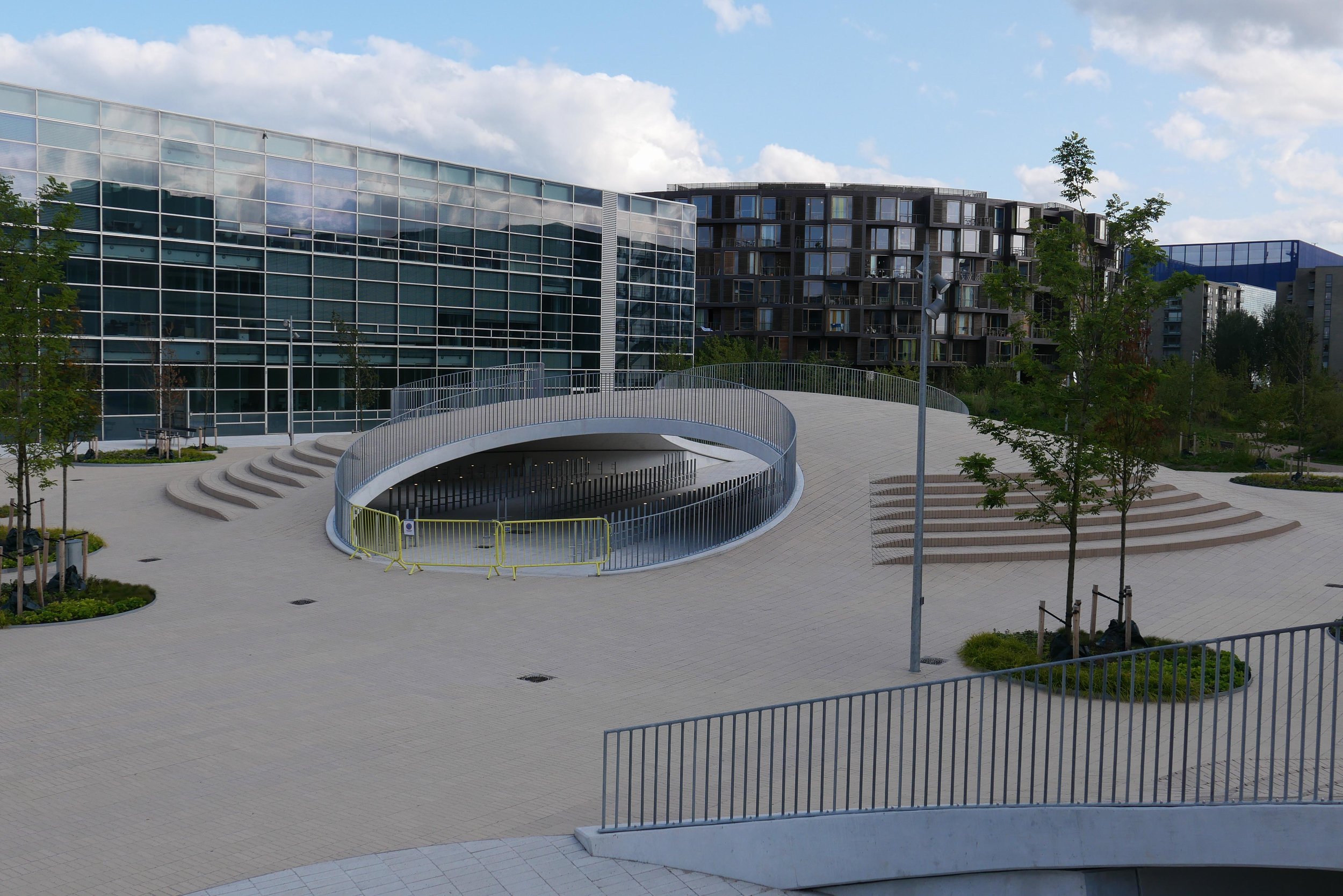

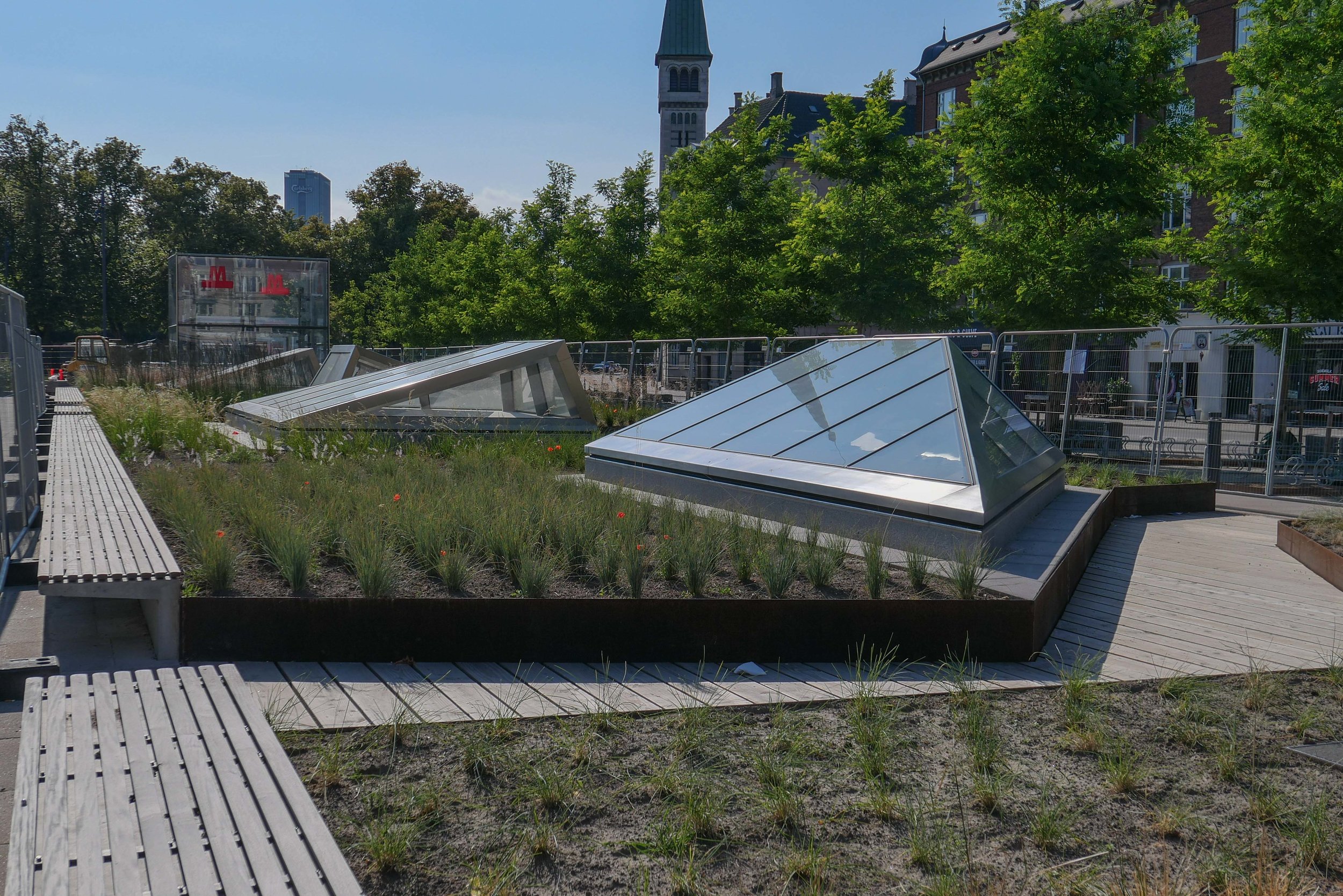

What is interesting about Blågårds Plads, and also of course the building work in the 1880s and 1890s in Copenhagen as the city expanded rapidly, is that actually it is remarkably similar to our own period, the first and second decades of this century, as a phenomenal number of new apartment buildings are constructed along the harbour to the north and south and across Amager in Islands Brygge and Ørestad.

The streets around Blågårds Plads went from a slightly untidy and piecemeal growth of houses and commercial properties with lots of gardens and open spaces in 1870 to one of the most deprived and densely packed areas of Copenhagen just 30 years later.

What was the problem with those buildings when so many apartments of the same period in other areas of the city survive and are popular places to live?

If there was criticism of the demolition of those apartments around Blågårds Plads in the 1980s was that simply fear of change? The buildings new then are now in their turn 30 years old and seem to be pleasant and well laid out with good courtyards and more open space but I noticed that they are not brick-built as they appear to be but, looking at the corners of the blocks, these seem to be pre-formed brick-faced panels on a steel frame. What was the life span of this housing that was planned in 1980 and are they a success for the residents and the community here?

Of course, no urban planner can prepare for anything and everything that the future might dump on us but even if this is the great period of recycling we should try not to recycle old problems.

the sculptures of Blågårds Plads