From Infrastructure to Public Space*

/Dronning Louises Bro in the evening from the city side

Our Urban Living Room, is an exhibition at the Danish Architecture Centre about the work of the Copenhagen architectural studio COBE with a book of the same title published to coincide with the exhibition, and both are subtitled Learning from Copenhagen.

A general theme that runs through the exhibition is about the importance of understanding a city as a complex man-made environment to show how good planning and the construction of good buildings, with the support of citizens, can create better public spaces that improve and enhance our lives.

One graphic in the exhibition, in a section about infrastructure, shows Dronning Louises Bro (Queen Louise’s Bridge) as the lanes of traffic were divided in the 1980s and compares that with how the space of the road is now organised.

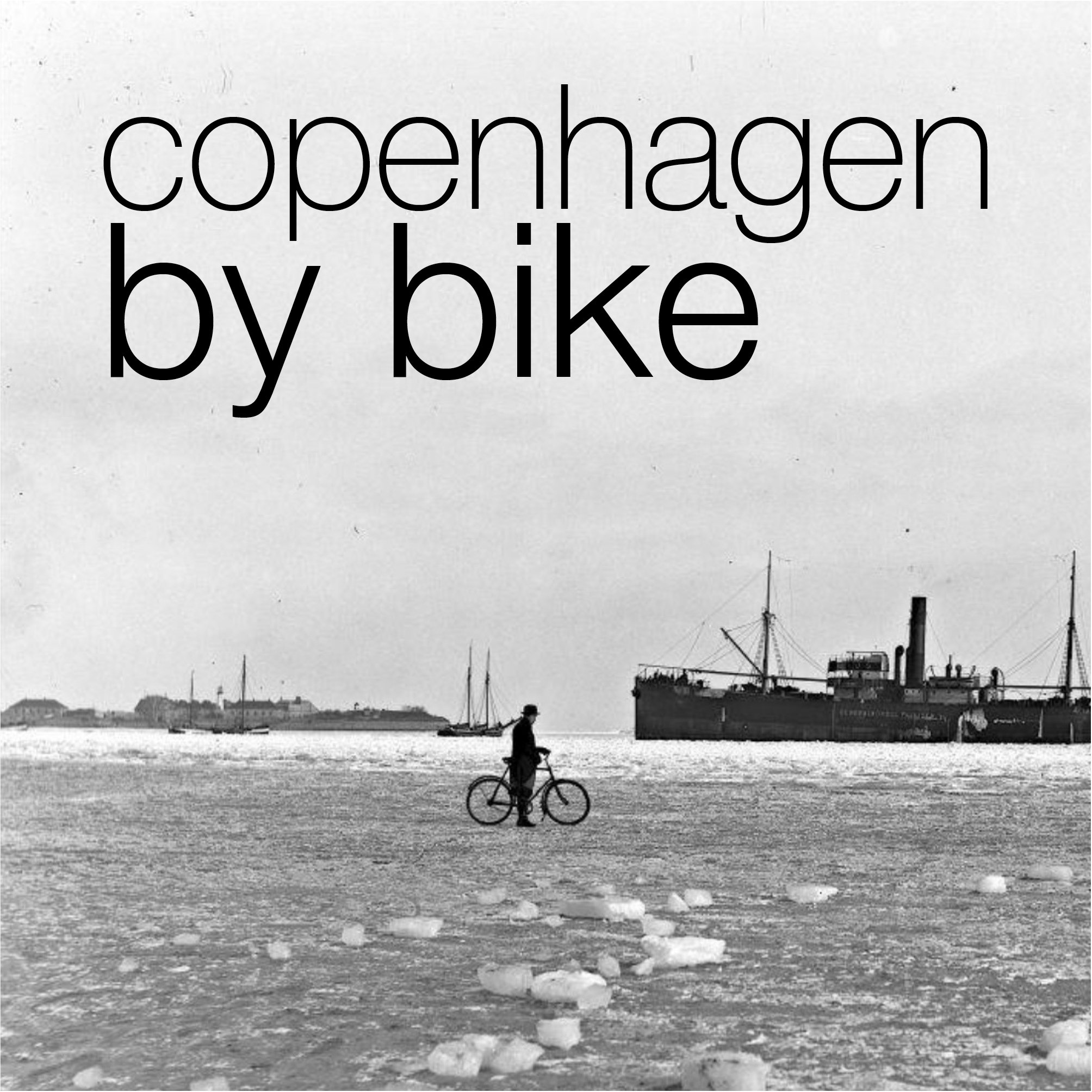

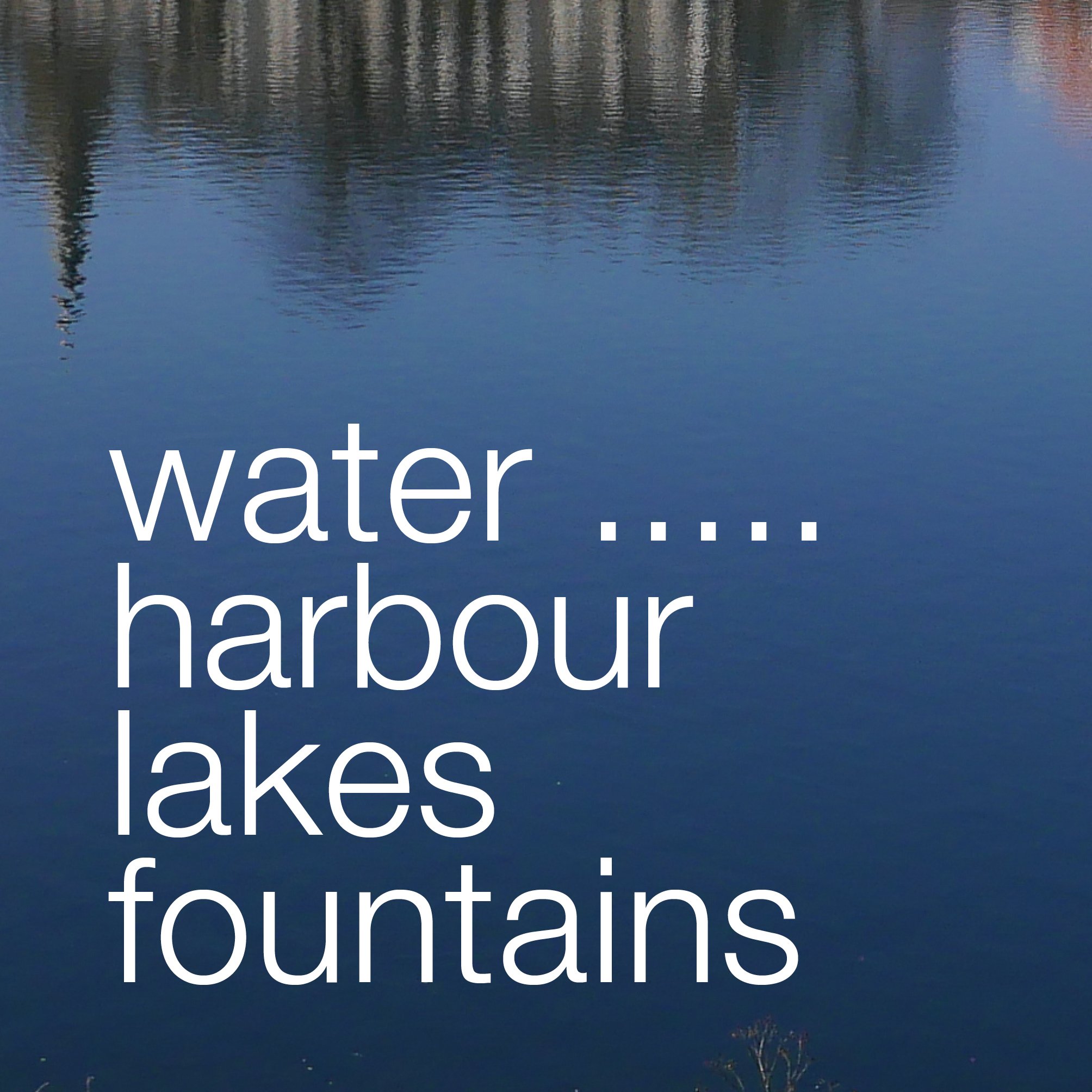

The stone bridge, in its present form dating from the late 19th century, crosses an arc of large lakes on the west side of the city centre and is the main way into the centre of Copenhagen from the north so many people have to cross the lakes on their commute into the city in the morning and then again in the evening as they head home. In the 1980s vehicles were given priority with 6 lanes for traffic - two lanes of cars in each direction and in the centre a tram lane in bound and a tram lane heading out - so the pavements on each side were just 3 metres wide and cyclists had to compete for space with cars.

Now, the width of the lanes given over to vehicles has been narrowed down to just 7 metres in the middle for a single lane for driving into the city and a single lane heading out but on each side there are dedicated bike lanes that are each 4 metres wide and then generous pavements that are 5 metres wide on each side of the bridge for pedestrians. So the space for cars and the space for pedestrians and cyclists has been swapped around. The bridge is just as busy - if not busier - with an almost-unbelievable 36,000 or more cyclists crossing each day and the pavements are actually a popular place for people to meet up … particularly in the summer when the north side of the bridge catches the evening sun so people sit on the parapet or sit on the pavement, leaning back against the warm stonework, legs stretched out, to sunbathe, chat or have a drink.

graphic showing changes made to the width of the traffic lanes over the bridge ... taken from an information panel for the exhibition Our Urban Living Room at the Danish Architecture Centre

the bridge looking towards the Søtorv apartments on the city side

even in November there can be enough sun so that it is warm enough to sit and wait or sit and chat

How many people crossing the bridge realise just how many dramatic changes to the city are reflected in the history of the bridge itself? Until the late 19th century what is now the inner city was still surrounded by the high banks of the city defences and there were few buildings in the area between the outer ditch and the lakes - so across what is now Nørreport railway station, Israels Plads and the wide streets of apartment buildings beyond was open land. In fact the lakes were irregular in shape and there in part as an outer defence and in part as a source of ‘fresh’ drinking water for the city. The stone edges and wide gravel paths around the lake, now a popular place to walk, date only from work of 1928.

the well known painting of the lakes in the early 19th century by the Danish artist Christen Købke and now in the collection of Statens Museum for Kunst - the National Gallery in Copenhagen

There was a bridge over the lakes at this point from the 16th century onwards but it was only when the city defences were demolished about 1870 and blocks of apartments were built between the lakes and the site of the old north gate - hence the name Nørreport for the railway station - that a new bridge was commissioned that opened in 1887.

An even grander bridge had been proposed but that scheme was abandoned although this important approach to the city was part of some very ambitious planning. Søtorv - four enormous apartment buildings on the city side of the bridge were designed in the style of French chateaux with a total frontage towards the lakes of 240 metres and in the green areas on either side of the bridge, on the city side, are statue groups - the figure of the Tiber on one side and the Nile on the other - so pretty grand aspirations and pretty grand planning from the worthy citizens ….. even by modern standards. At the centre of the new wide streets and squares and blocks of apartments built after 1870 was a large open square that was a food market so presumably in part the bridge was that wide because it was seen as one main way into the city each day for produce for the market.

The market? Now the incredibly popular food halls of Torvehallerne and Israels Plads … the square that is another area recently transformed by COBE.

the lake, Søtorv and the bridge from the north in the late evening

* the title of this post is a section heading from the exhibition Our Urban Living Room and a chapter heading in the catalogue