Work is moving forward fast on Ørkenfortet, the Desert Fort - the large office building that is at the centre of the harbour at the Christianshavn end of Knipplesbro - the central bridge that crosses the harbour between the centre of the city and Christianshavn.

The interior at all levels has been gutted and all original windows and all external cladding have been removed. Work has started on cutting down new internal courtyards or light wells within the concrete structure of the block and on removing hefty concrete retaining walls along both the street frontage towards Torvegade and at the level of the quay on the end of the building towards the harbour that formed a base for the building.

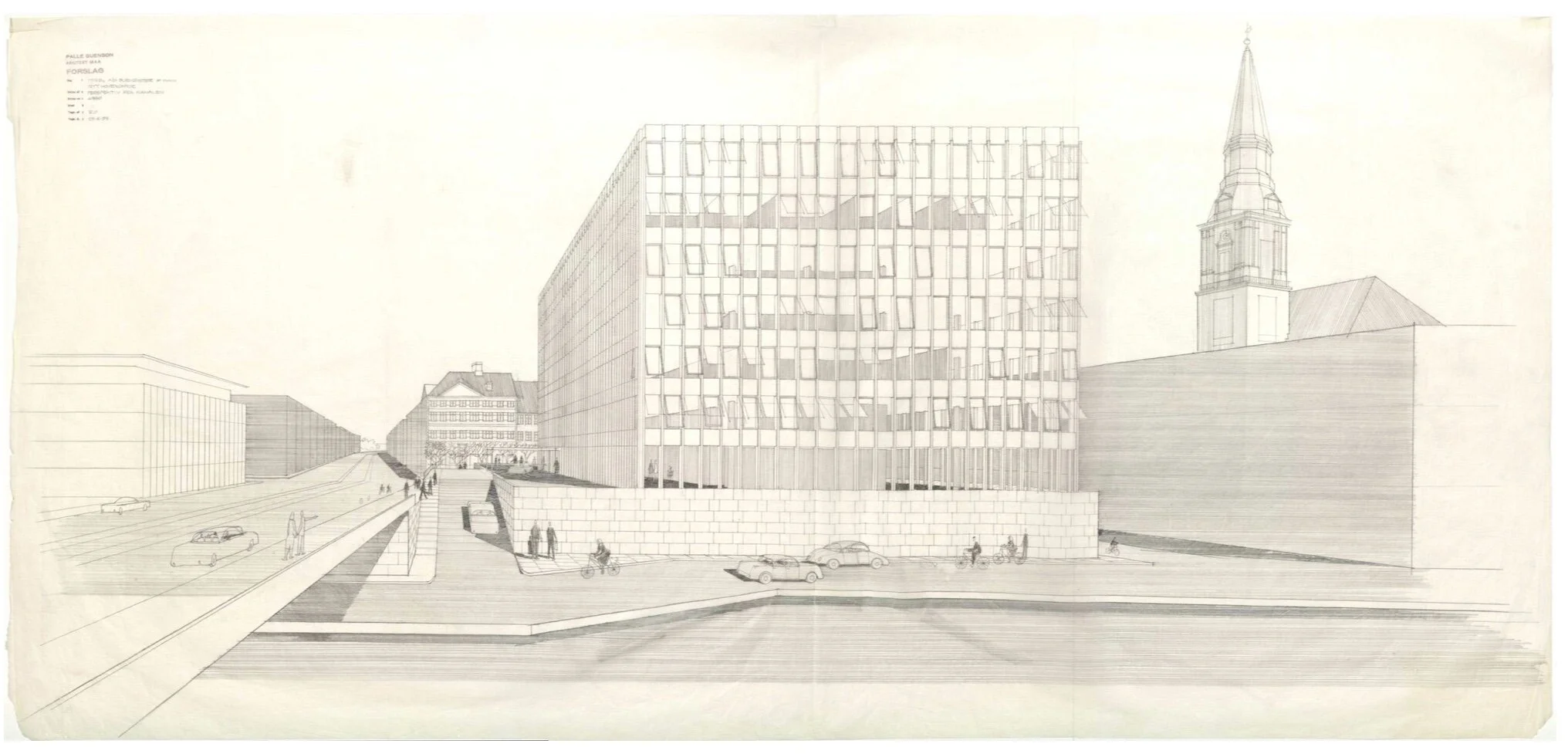

Ørkenfortet was designed by Palle Suenson (1904-1987) and was completed in 1962 as offices for Burmeister & Wain who were a well-established and major engineering and ship-building company in the city.

They had been established under that name in 1865 and, by the middle of the last century, their main ship yards were at Reshaleøen - at the north end of the harbour - where the main dry dock survives along with the some of the huge sheds and buildings of the yards but the engine works were here at the south end of Christianshavn, immediately south of this office building.

These extensive engineering yards on Christianshavn shut in 1993. Although some of the earlier buildings - including former drawing offices and the works' gates - survive, most of the buildings along the quay towards the harbour were demolished and wharves and docks were filled in for the site to be redeveloped with large new apartment buildings and extensive office buildings that were designed by the architects Henning Larsen.

Several of these office buildings along the harbour were occupied by the Danish headquarters of Nordea Bank including the office building by Suenson but in 2017, the bank moved their offices to a new site, close to the metro station at DR Byen, and the main office building from the 1960s became available for redevelopment.

This is all fairly straightforward history - the recent history of the site and of the building - but what I don't understand is the planning decisions then made for this key site at the very centre of the harbour.

Of course, I can see the logic and the reasons for planning decisions made in the 1950s. As Denmark emerged from the war, the priorities were for economic recovery. These ship-building and engineering works were not only a major employer in the city but these were highly skilled and, presumably, relatively well-paid jobs. The company was well established and, if nothing else, emerging from the widespread destruction of the war, there was an obvious market for new engines and new ships to replace what had been lost. Perhaps, and even more significant at that stage, although the harbour was, in terms of topography, at the heart of the historic city, attitudes to the harbour then were very different.

Then , north of Knippelsbro, were the working naval docks, with all that meant, and with the only road access through Christianshavn. Through the centre of the harbour and below or south of Knippelsbro was a working port with all that meant. Polite, middle-class society in the city would have seen the harbour as a major resource but that was as a major financial resource, so a massive new office building for Burmeister & Wain would not have been seen as an eye sore … even though its within sight of the 17th-century buildings of the exchange, on the other side of the harbour, and close to the magnificent warehouses from the 18th century, of the Asiatic Quay and Gammel Dok, on the other side of the road … but it would have been seen as an astute and positive show of confidence in the industries of the city and in their future.

It has only been with the decline of the dockyard and the working port and those industries that the harbour had to look for and has certainly found a new purpose at the heart of the city but I'm not sure how this massive hotel development actually makes a positive contribution.

On the side away from the harbour, the existing building looms over Strandgade - an exceptionally important street of historic buildings with many that date back to the early 17th century - and it overshadows the stunning Christians Church by Nicolai Eigtved that was built in the 1750s.

The block of the existing building is massive - one of the largest and certainly one of the most prominent at the centre of the harbour. It's 90 metres long by 31 metres deep and about 30 metres high. It's not a bad building as such but simply a product of its period and certainly not the best building for this location.

In terms of planning, the retention of the building and its conversion to a hotel by the Hilton Group, raises lots of issues.

It will have about 400 rooms so how will Christianshavn cope with the amount of traffic a hotel of this size generates with visitors coming and going, staff arriving and leaving and delivery lorries coming and going?

And why, when it is such a large building anyway, has permission been given to add a whole extra floor on the top that will increase the visual impact of the building and ensure that it overlooks even more properties. I can see that a roof-top dining room and roof terraces are a huge bonus for the hotel but I cannot see what they contribute to the harbour or to the neighbourhood.

Consent has been given to remove the hefty concrete retaining wall along the lowest level towards the quay but this means that the hotel can colonise and make use of the quayside as an asset for the hotel although citizens gain little from this apart from some new steps up from the quay to the bridge on this side. Note there are already steps up to the bridge on the other side of Torvegade and steps on both sides of the bridge on the city side so access from the bridge to the quay is actually adequate.

Almost-certainly, the city would not have given permission for a building of this size and prominence if the site had been empty land or there had been much lower buildings here.

Surely, it would have been better for the city and for the harbour if the building from the 1960s had been demolished and replaced with buildings that were lower and more compact, and with new buildings that reinstated or created a reasonable street frontage to the road up to the bridge and a more appropriate and more respectful frontage towards Strandgade.

Planning Statement - appendix to the Local Plan

notes:

In Danmarks Kunstbilbliotek / the Danish Art Library in Copenhagen there is a drawing of the building by Palle Suenson Inv. nr. 53296 - a perspective from Knippelsbro

While tracking down information on the building I came across a web site that revealed that the building was given a nickname by locals who called it Røven or The Arse. Initially, I assumed that was because the building was thought to be butt ugly but actually it was because at lunchtime workers in the office came out onto the forecourt and sat along the parapet of the wall along Torvegade and, for people walking along the pavement below, the only thing that could be seen from the street was a line of backsides.