Bispeengbuen - a new plan

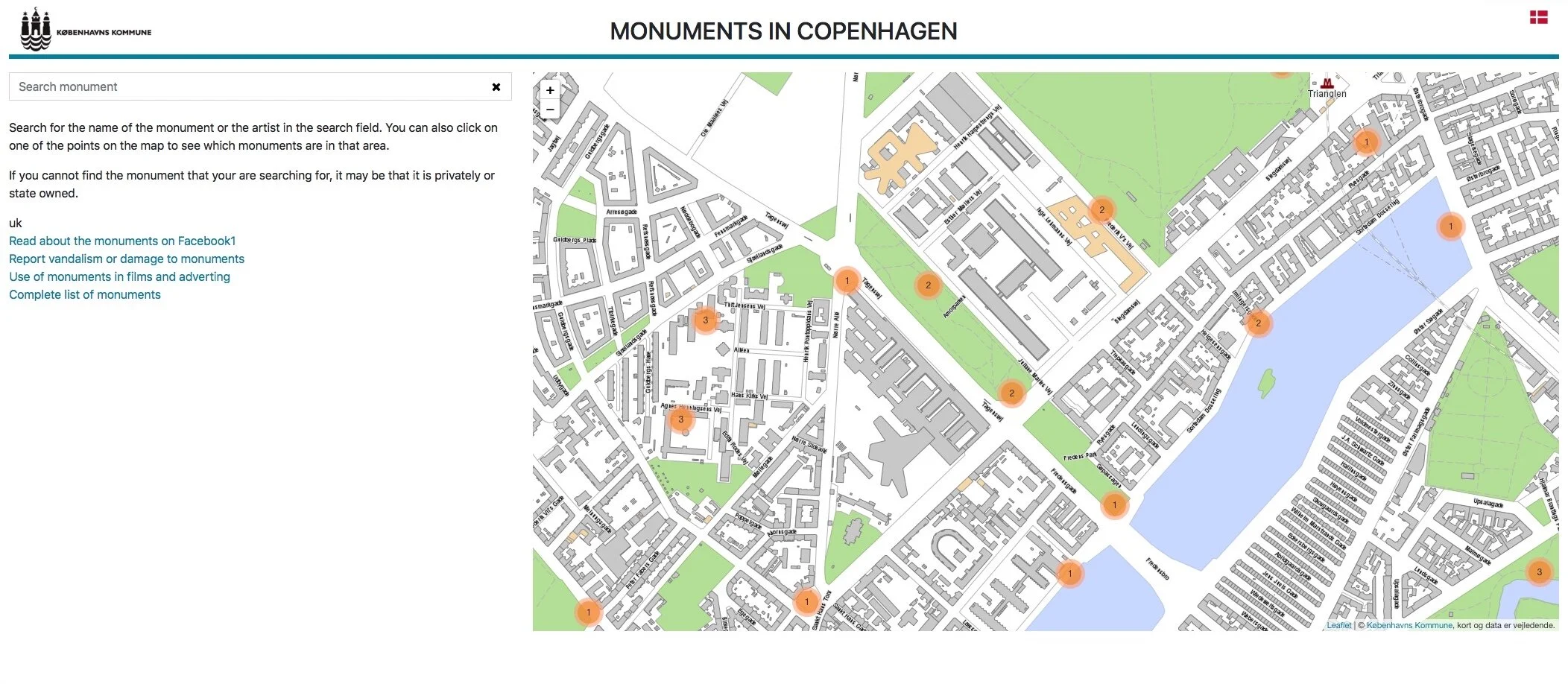

/Yesterday, an article in the Danish newspaper Politken reported that planners and politicians in Copenhagen might have come to a decision on the fate of Bispeengbuen - the section of elevated motorway that runs down the border between Frederiksberg and the Nørrebro district of Copenhagen.

One of several major schemes to improve the road system in the city in the late 1960s and 1970s, Bispeengbuen was planned to reduce delays for traffic coming into the city from suburbs to the north west.

At the south end of the elevated section, at Borups Plads, traffic, heading into the city, drops back down to street level and continues first down Ågade and then on down Åboulevard to the lakes and, if it is through traffic, then on, past the city hall, and down HC Andersens Boulevard to Langebro and across the harbour to Amager.

Between the elevated section and the lakes, the road follows the line of a river that, from the late 16th century, had flowed through low-lying meadows - the Bispeeng or Bishop's Meadow - and brought fresh water in to the lakes. In 1897, the river was dropped down into a covered culvert and it still flows underground below the present traffic.

From the start, the elevated section was controversial as it cuts past and close to apartment buildings on either side - close to windows at second-floor level - and the area underneath is gloomy and generally oppressive. Traffic is fast moving and generates a fair bit of noise and it forms a distinct barrier between the districts on either side.

There has been an ambitious plan to drop the road and its traffic down into a tunnel with the river brought back up to the surface as the main feature of a new linear park. The full and very ambitious plan - for ambitious read expensive - was to extend the tunnel on to take all through traffic underground, to Amager on the south side of the harbour.

There has been talk of a less expensive plan to demolish the elevated section, to bring all traffic back down to street level, which would be cheaper but would not reduce the traffic and would leave the heavy traffic on HC Andersens Boulevard as a barrier between the city centre and the densely-populated inner suburb of Vesterbro.

This latest scheme, a slightly curious compromise, is to demolish half the elevated section. That's not half the length but one side of the elevated section. There are three lanes and a hard shoulder in each direction and the north-bound and city bound sides are on independent structures. With one side removed, traffic in both directions would be on the remaining side but presumably speed limits would be reduced - so, possibly, reducing traffic noise - and the demolished side would be replaced by green areas although it would still be under the shadow of the surviving lanes.

It was suggested in the article that this is considered to have the least impact on the environment for the greatest gain ... the impact of both demolition and new construction are now assessed for any construction project.

There is already a relatively short and narrow section of park on the west side of the highway, just south of Borups Plads, and that is surprisingly quiet - despite alongside the road.

On both sides of the road, housing is densely laid out with very little public green space so it would seem that both the city of Copenhagen and the city of Frederiksberg are keen to proceed. Presumably they feel half the park is better than none although I'm not sure you could argue that half an elevated highway is anywhere near as good as no elevated motorway.

The situation is further complicated because the highway is owned and controlled by the state - as it is part of the national road system - so they would have to approve any work and police in the city may also be in a position to veto plans if they feel that it will have too much of an impact on the movement of traffic through the area.

update - Bispeengbuen - 14 January 2020

update - a road tunnel below Åboulevard - 15 January 2020

note:

Given the brouhaha over each new proposal to demolish the elevated section of the motorway, it is only 700 metres overall from the railway bridge to Borups Plads and it takes the traffic over just two major intersections - at Nordre Fasanvej and Borups Allé - where otherwise there would be cross roads with traffic lights. I'm not implying that the impact of the road is negligible - it has a huge impact on the area - but, back in the 1960s, planners clearly had no idea how many problems and how much expense they were pushing forward half a century with a scheme that, to them, must have seemed rational.

My assumption has been that the motorway was constructed, under pressure from the car and road lobby, as part of a tarmac version of the Finger Plan of the 1940s.

The famous Finger Plan was an attempt to provide control over the expansion of the city, and was based on what were then the relatively-new suburban railway lines that run out from the centre. New housing was to be built close to railway stations and with areas of green between the developments along each railway line .... hence the resemblance to a hand with the city centre as the palm and the railway lines as outstretched fingers.

Then, through the 1950s and 1960s, the number of private cars in Copenhagen increased dramatically and deliveries of goods by road also increased as commercial traffic by rail declined.

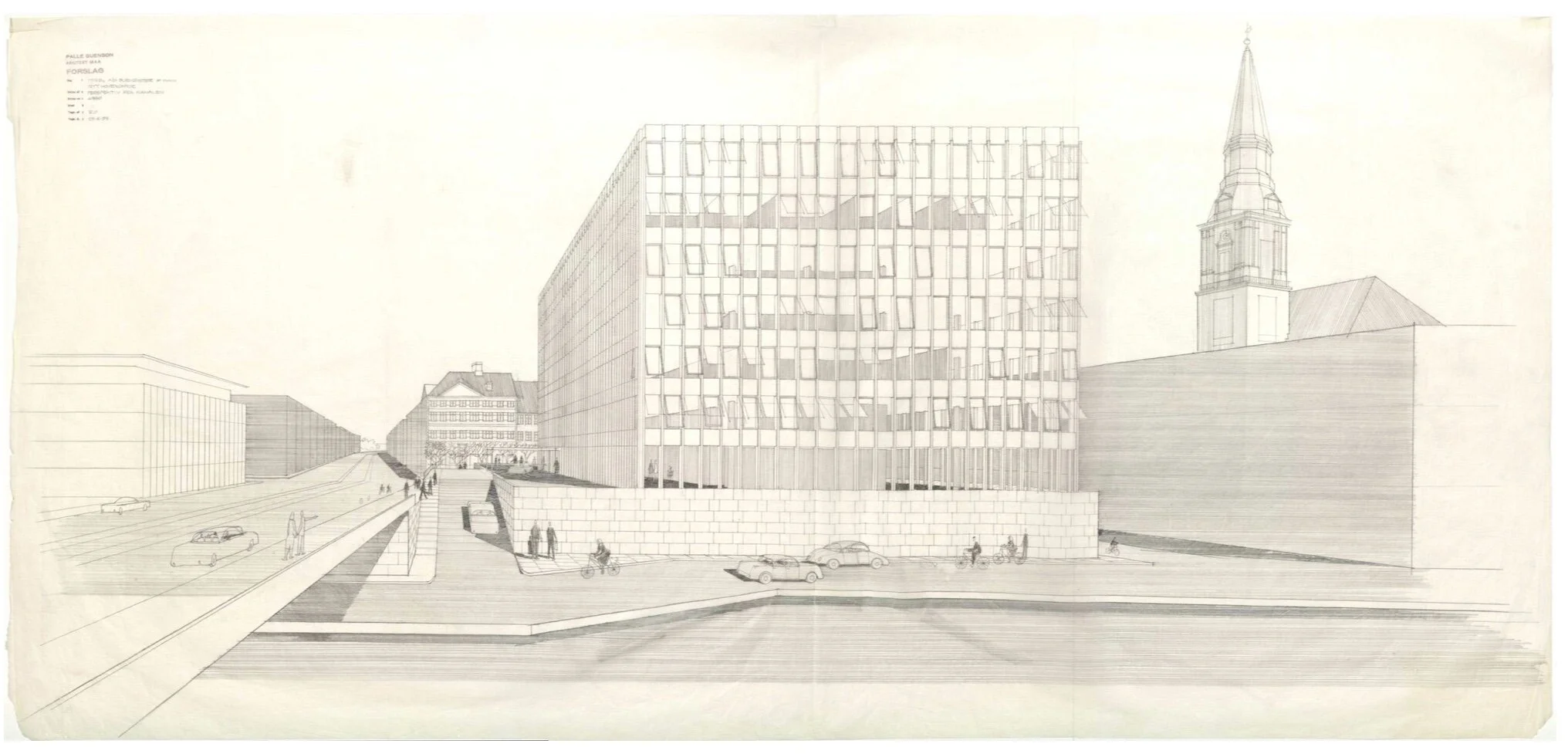

I don't know who the traffic planners were in Copenhagen in the 1950s and 1960s but, looking back, they barely appreciated old building or existing communities, and, presumably, looked to LA and, possibly, to the Romania of Nicolae Ceaușescu for inspiration. Their ultimate aim, in their professional lives, seems have been to design a perfect motorway intersection where traffic flowed without any delays.

They wanted to build a motorway down the lakes and when that was thwarted they proposed a massive motorway system that was to be one block back from the outer shore of the lakes - sweeping away the inner districts of Østerbro and Nørrebro - and with new apartment buildings along the edge of the lake - between their new motorway and the lake - that would have formed a series of semi-circular amphitheatres looking across the lakes to the old city. The whole of the inner half of Vesterbro, including the meat market area, and the area of the railway station would have become an enormous interchange of motorways where the only purpose was to keep traffic moving.

We have to be grateful that few of those road schemes were realised but there is also a clear lesson that, however amazing and visionary a major plan for new infrastructure may appear, it can, in solving an immediate problem, create huge problems for future generations to sort out.