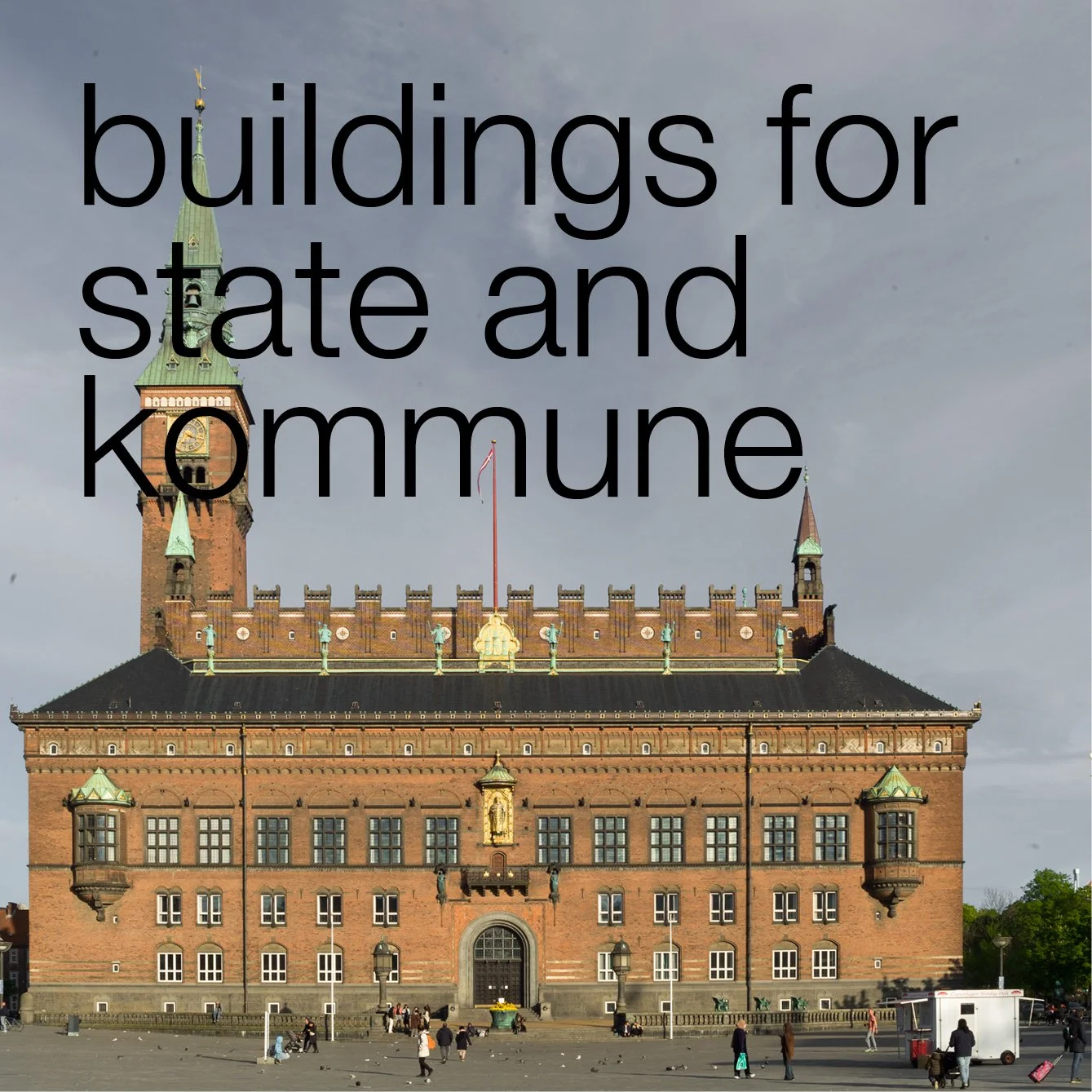

Rødovre City Hall

/

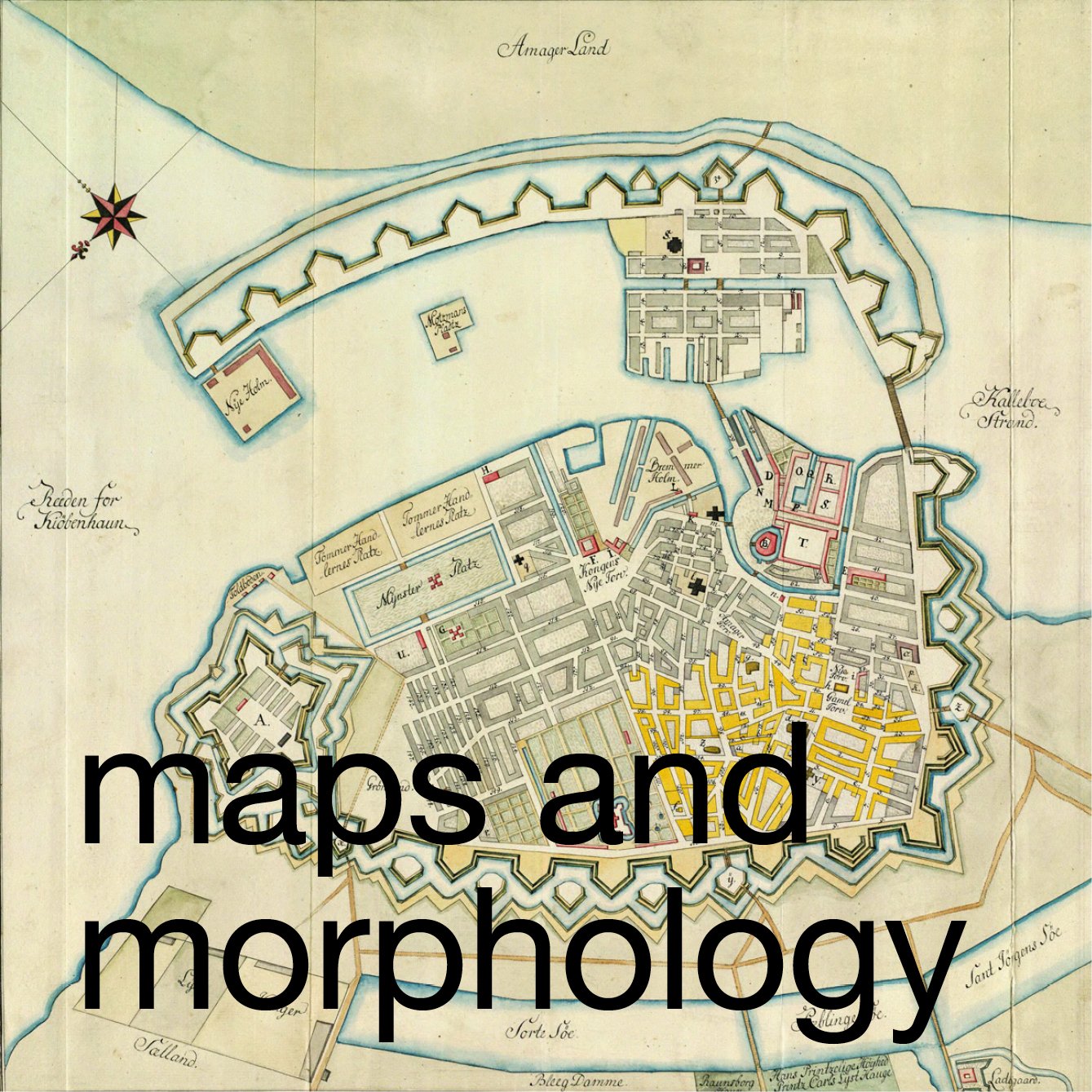

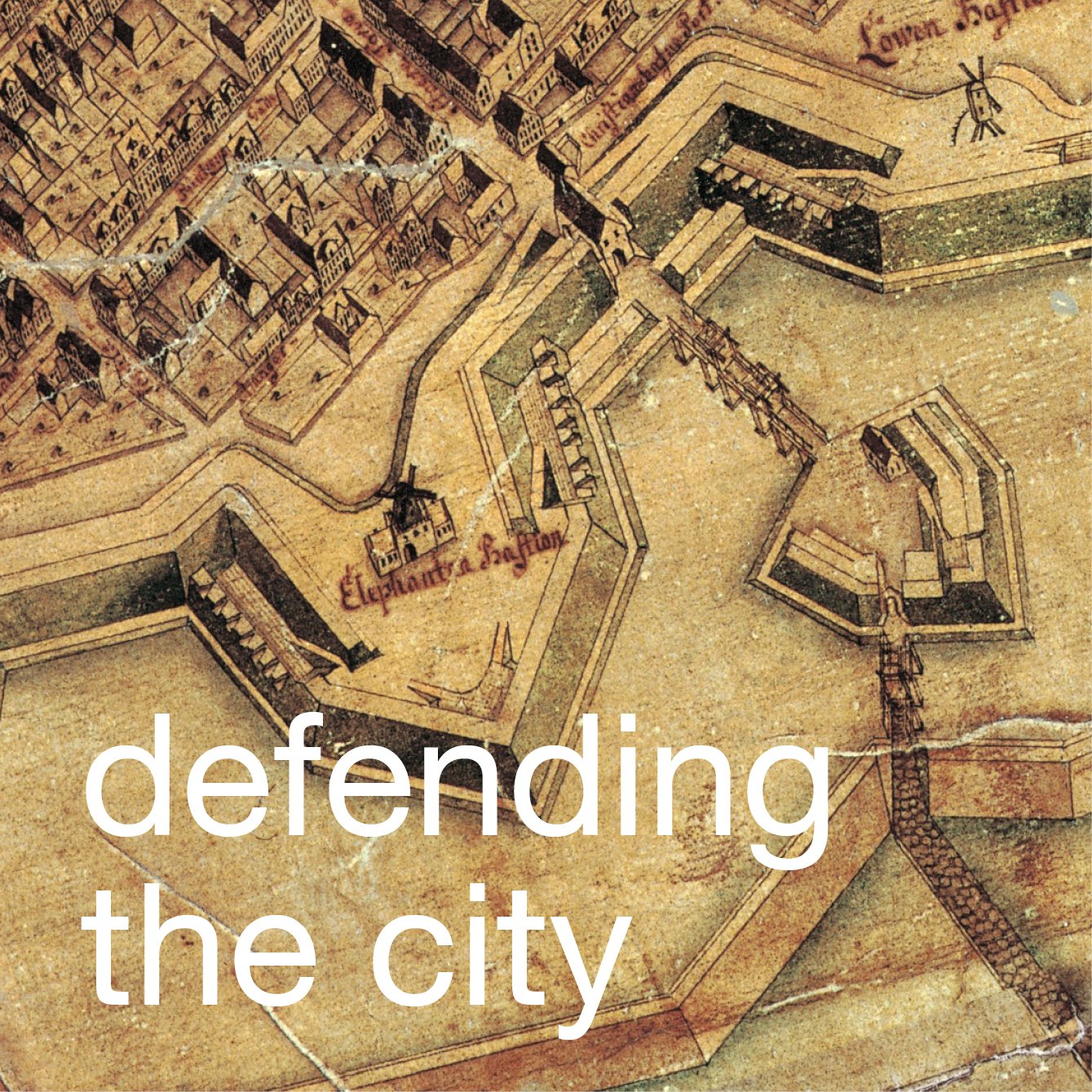

Rødovre is a suburb of Copenhagen and is about seven kilometres west of the centre of the city but inside the outer defences of Copenhagen - the Vestvolden ramparts - that date from the middle of the 1880s.

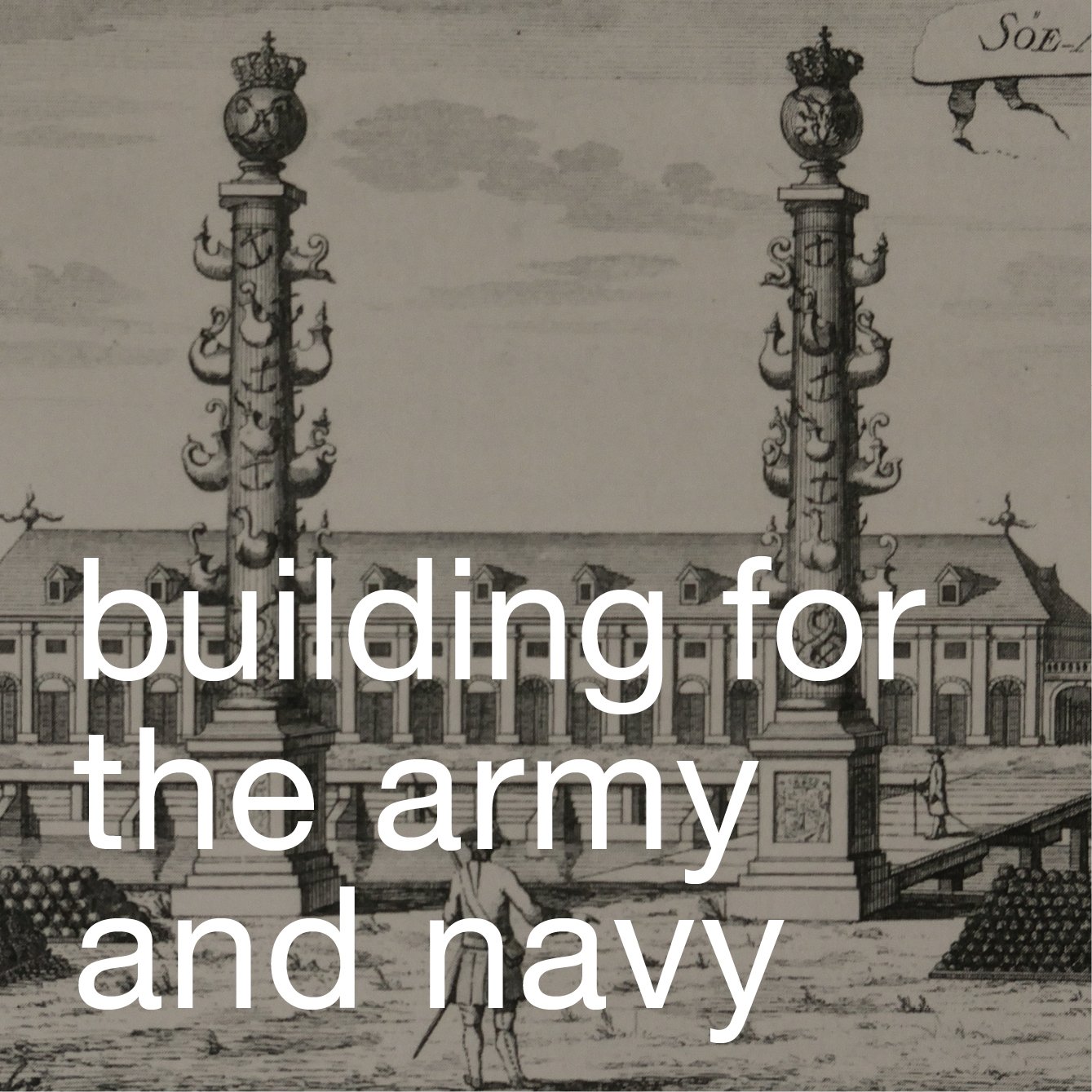

Rødovre became an independent municipality in 1901, presumably a rationalisation of local government that reflected growth in the population in the late 19th century but there was extensive building of new houses before and after the second world war. As well as housing here - Islevvænge with 194 row houses - Arne Jacobsen designed a major group of buildings in the centre that included a new City Hall* completed in 1956; a long range of apartments to the east of the City Hall that date from 1959 and between them a library that was designed in 1961 and finished in 1969.

the site

The City Hall is on the west side of a large public square … a rectangular paved area that has avenues of trees and two shallow canals all running north south. The library is on the east side of the square and the entrance doors of the library and the council offices face each other on a cross axis of the public space.

Across the south side of the square is a main road, Rødovre Parkvej, and opposite, on the other side of that main road, there is now a large central shopping complex, which - although it was not designed by Jacobsen - forms an important group with the civic buildings.

To the west, beyond the office range of the City Hall and its council chamber is a large open grassed area - between the City Hall and a main road, Tårnvej - and it is from that side, given space to stand back from the building, that the thin elegance of the overall design of the city Hall can be best appreciated.

the City Hall

Three storeys high, but with a basement under the full length, the office building of the City Hall is 91 metres long from north to south but just 14 metres deep. The narrow north and south ends are clad in dark green stone from Norway but the long east and west fronts of the building have continuous runs of windows forming a regular and consistent grid with an unbroken run of tall but narrow windows across each level with paired grey panels below each window. Here is the use of a curtain wall system at it’s purest with nothing on the facades to mark the level of any floor structure; no expression of any internal cross walls and no attempt to express any sense of subdivisions across the front by any stepping forward or stepping back of the wall line.

Secondary doors at each end, where there are service staircases, barely break the fenestration pattern and even the entrance door is barely expressed on the facade itself … three standard-width windows are dropped down to the level of an external step for two narrow doors flanking a fully glazed panel. Thereare no architraves, pillars or pediments you would expect in a 19th-century town hall to show this was a grand civic building. It could hardly be more low key or therefore more accessible or democratic.

This main entrance into the offices from the plaza does have a double canopy supported on metal uprights … the inner and lower canopy cantilevered out immediately above the doorways and the same width and supported with single metal upright on each side. The main porch, on four uprights like a large table, is rectangular in plan and set along the front and in part overlaps the lower canopy but is not centred on it. The metal uprights are not under the roof but inset from the corners and faced immediately against the edge of the roof slab.

Council Chamber from the west with the offices beyond

Council Chamber and the link corridor from the south

A single-storey council chamber with two committee rooms, projecting to the rear of the main three-storey range, is on the axis of the entrance into the building and linked to the council offices by a glazed, single-storey corridor. The corridor has the same external metal uprights as the entrance porch with very large windows set immediately behind.

There is a design drawing, now in the collection of Danmarks Kunstbibliotek in Copenhagen, that shows the public square at the front of the City Hall from the south. The avenues of trees are shown in rigid lines with thin trunks with the canopy cut high but what is more interesting is that the foliage itself is clipped square and flat to the underside, sides and top, more like boxes on sticks than anything in nature, so Jacobsen saw even the planting as part of the very regular and controlled geometry of the group of buildings.

The entrance hall, with the main staircase of the building on its south side, is the full depth of the range and on the west side towards the Council Chamber, is fully glazed for the full height of the building. From the entrance hall, this creates an impression that the areas on either side of the corridor to the Council Chamber are actually internal courtyards although in fact they are open and accessible from the north and the south.

In the Council Chamber the arrangement or orientation of solid wall and walls of glass swaps round - with windows to the north and south but blank stone walls to the east, towards the office block, and to the west, towards the area of lawn and the main road. In part this was determined by the construction because the long east and west walls carry the roof, so that there are no internal columns, but surely it was also in part symbolic because citizens, walking along the road across the south side, could look into the Chamber and see their council in action.

geometry and the site

The building is designed over a regular grid of squares with the dimensions of the squares being determined by the width of a single window to the east or west so the office range is 92 windows long and the equivalent of 14 windows deep although the north and south ends are blind.

Overlaying the grid are a series of axes and cross axes through the building. These start in the public square where the north/south axis is reinforced by the line of two canals that are in line and run across the front of the library. There is a cross axis, between the canals, between the entrance into the library to the east and the main entrance into the City Hall to the west. This axis continues on, through the City hall building, into the corridor to the Council Chamber block beyond but is interrupted by a major cross axis within the office building, that runs north south down the centre of the office block on either side of the entrance, down wide spine corridors between two lines of columns that support the concrete structure of the floors.

Within the council-chamber block, there is a further cross axis with the larger Council Chamber to the south lit by windows across its south wall and two committee rooms to the north lit by windows to the north.

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek in Copenhagen on their web site has published some of the drawings by Jacobsen in their collection including some

structure

In the building, both its plan and the structure are strictly rational. The entrance hall, with the main staircase, is nine window bays wide and runs across the full depth of the building and because the stair structure cuts through and weakens the floor system, there are major cross walls to the north and south of the entrance hall.

At both the north and south ends of the main block there are secondary staircases and service rooms so again there are cross walls which at each end are set four windows in and again reinforce the structure where staircases cut through the floors.

The entrance hall is not actually central to the block - with 25 windows to the south, between the entrance and the south staircase, and 49 windows between the entrance and the four bays of the north staircase.

Office areas on either side of the entrance have a wide corridor running down the centre - down the spine of the building - with columns on both sides that support the concrete floor structure … a form reminiscent of the structure of the contemporary open-plan office building by Jacobsen for A Jespersen. The columns on the west side, on the ground floor, are hidden by partitions hard against both sides of the columns and the void is used for services but on the east side of the corridor the partition is thin with glazed panels at the top that are set immediately behind the columns.

Down the building there are columns against the cross walls and then equally spaced columns define 6 major bays of the structure to the south of the entrance and 12 bays to the north.

As with the Jespersen building in Copenhagen, the underside of the concrete floor structure tapers - it gets thinner towards the window wall - and the ceilings of the spaces follow that slope.

interior

The main staircase, a dog-leg plan with half landings towards the window side, is on the south side of the entrance hall and is a thin and elegant design in steel and glass and seems to be suspended in the space.

Throughout the building, the colours used, the use of wood for wall finishes and the furniture and fittings were all carefully modulated by Jacobsen.

Light fittings and furniture were all to Jacobsen design - the Munkegård Lamp is used throughout the building and furniture included Ant and the Series 7 chairs.

In the Council Chamber the main table in rosewood and steel forms a C shape and here the chairs are from the Seven series … the 31207 with arms and upholstered in black leather. Designed in 1955 these chairs are contemporary with the building. The Council Chamber has a grid of up lighters suspended below the ceiling on a framework of wires and metal rods.

Here at Rødovre City Hall, the concrete structure and the use of a curtain wall system of glazing allowed Arne Jacobsen to develop a deceptively simple style of architecture that is in reality complicated, sophisticated, highly controlled and completely rational and stripped back to realise a building of thin and refined elegance.

note:

* For English readers the description of Rødovre as a city might seem curious as the population is under 40,000 but in Danish the word by is used for both a city or a town. Here the term City Hall has therefore been retained, rather than changing it to town hall, to remain consistent with the use of the phrase in works like the book on Jacobsen by Carsten Thau and Kjeld Vindum.