Chairs at Designmuseum Danmark

/looking at chairs to left or right or above or below you can see how a shape or type of chair evolved or how a form can be re-interpreted in a different material

At Designmuseum Danmark there is a relatively new display for their collection of modern chairs where the chairs are arranged by type rather than by designer or by displaying the chairs in chronological order.

This typography puts the chairs into relatively distinct and easily identified groups where each group is defined by a form or shape and by the style of a chair … the form of the chair, techniques of working with a material and details of construction and style, all being closely interrelated.

Most of the chairs shown date from the 20th century and were made by Danish cabinetmakers or Danish manufacturers although several older chairs, several more recent Danish chairs and some chairs from outside Denmark have been included where they provide evidence for how or why or when a specific Danish design evolved or if they are relevant evidence from a specific or wider social or historic context.

Most of the chairs are made in wood but there are chairs with frames in metal tube and there are metal wire and even plastic chairs so there are interesting examples where closely-related designs - in terms of style and shape - can be seen in tube-metal alongside a version in bent-wood although obviously the techniques and the details of construction are very different.

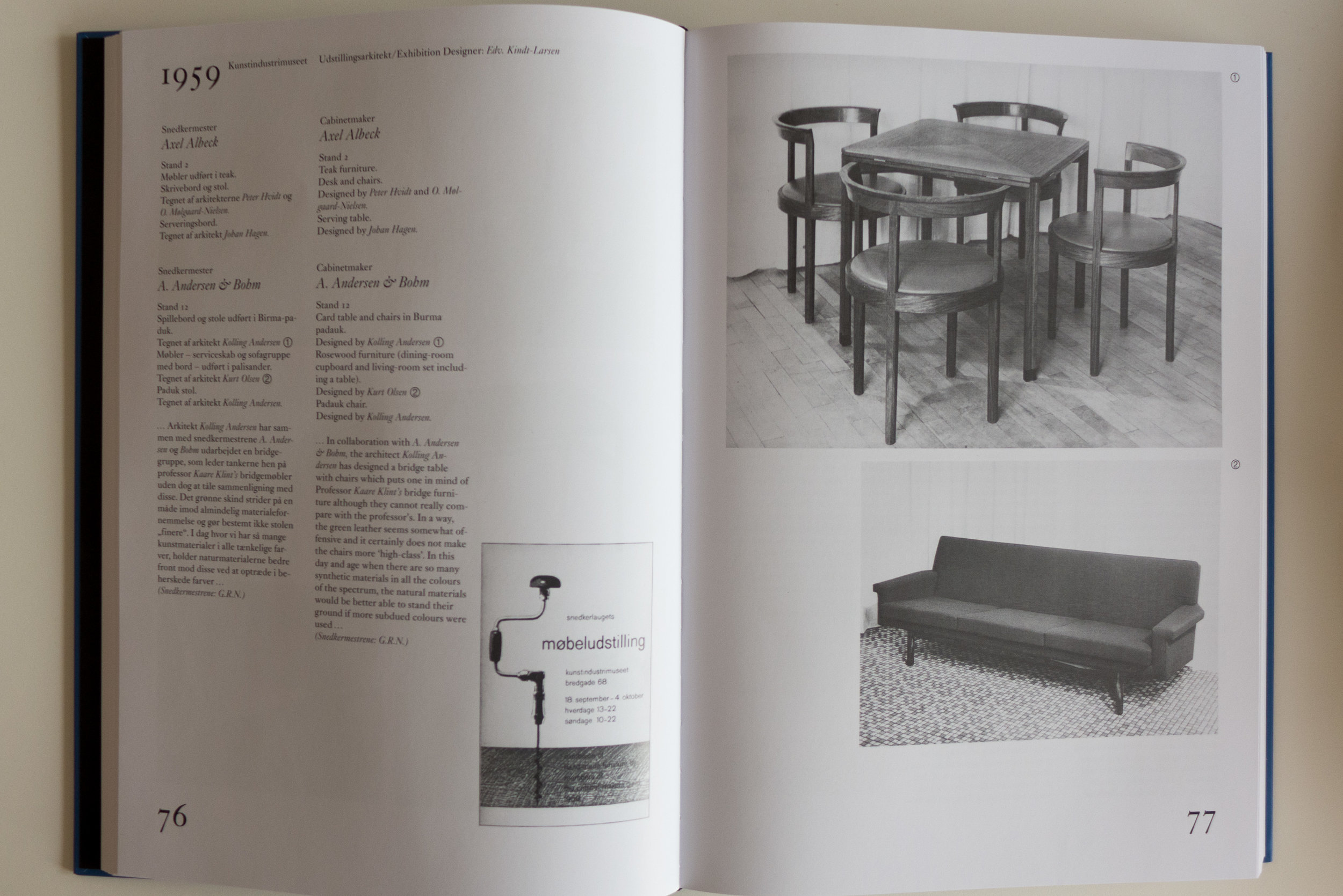

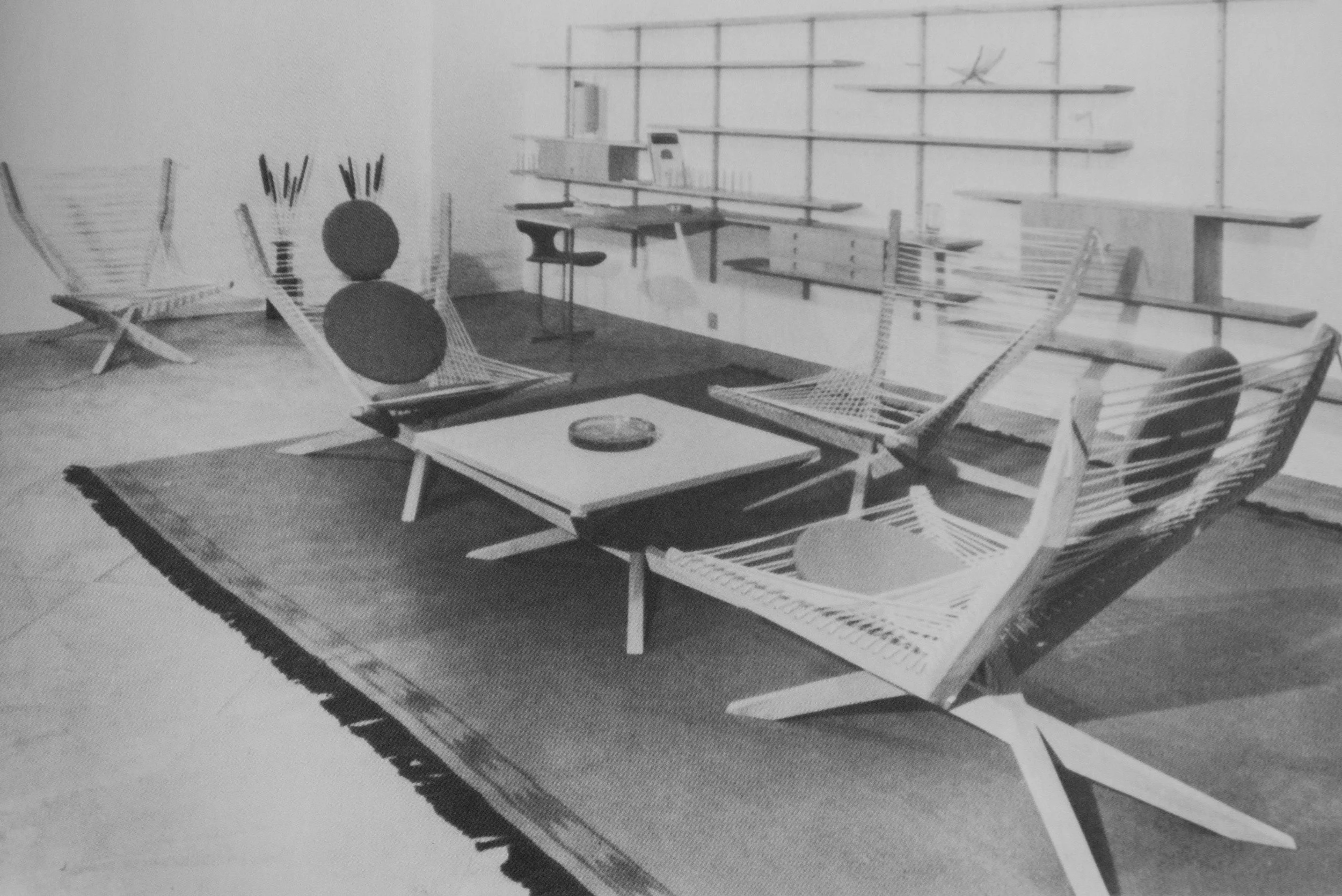

The main groups, defined by the museum, are Folding chairs and stools; Easy chairs - so generally lower and wider chairs - and Windsor chairs - with vertical spindles across the back to support the top rail or - in taller chairs - a head rest. Chippendale chairs have a sturdy frame of square-set legs - usually with stretchers between the legs and a relatively low back and when they have arms these are housed into the uprights of the back. There is a group derived from Shaker chairs, from America - often with horizontal slats across the back rest. Chinese chairs and steam-bent chairs, are similar to the Chippendale Chairs but are distinct in terms of the sitting position which is more upright and more formal and generally the top of the back rail sweeps round into arm rests as a single curve rather than in separate pieces. Round arm chairs and Klismos chairs also have curved and relatively low back rests that continue round into arm rests - with The Chair by Hans Wegner perhaps the most famous Danish example. A Klismos or Klismos Chair is a distinct classical or Greek type with a short but sharply-curved back rest across the top of the back uprights with legs that are usually tapered and splay out down to the floor in a curve. Shell chairs include chairs in moulded or shaped plywood, moulded plastic or metal with shapes that provide - usually in one piece - the support for the seat and back without a framework, and are usually on a separate frame of legs or on a pedestal, that itself can be made from a different material to the shell, although there are shell chairs where seat, back and support are all moulded. Moulded chairs with a shell in foam or plastic first appeared commercially in the 1950s and moulded plastic chairs have by this century become almost ubiquitous in the collections of most Danish manufacturers. The final group identified by the museum are Cantilever chairs where normally there is a strong base on the floor and some form of support for the front of the seat but no legs or support under the back of the seat - an interesting but not a common type in Denmark.

chair by PV Jensen Klint circa 1910

armchair by Kaare Klint 1922

JH505 the Cow Horn Chair by Hans Wegner 1952

Ant shell chair by Arne Jacobsen 1951

EKC12 in tubular steel by Poul Kjærholm 1962

PK15 by Poul Kjærholm 1978

all in the collection of Designmuseum Danmark in Copenhagen

The study and analysis of chair designs from different periods has been an important part of the training for designers in Danish schools of architecture and schools of design for a century.

In the 1920s, the architect Kaare Klint was responsible for the conversion and the fittings of the buildings of an 18th-century hospital to form an appropriate exhibition space for the museum of Danish design - then called the Kunstindustrimuseet Danmark. Klint taught design in the museum where he encouraged architects and furniture designers to study and draw historic pieces and to study and appreciate cabinet making techniques even if they were not craftsmen themselves and he emphasised the close relationship between design and the techniques of construction.

This division of chair types in the design museum is different from the groups set out by Nicolai de Gier and Stine Liv Buur in their important book Chairs' Tectonics where their primary divisions are by material and then by the form and structure … so they look specifically at how the seat, back rest and support or legs are joined or fixed together and take that as the starting point for their classification of chair types.

Designerof the new display: Boris Berlin of ISKOS-BERLIN Copenhagen

Curator of the collection: Christian Holmsted Olesen.

Graphic design: Rasmus Koch Studio.

Light design: Jørgen Kjær/Cowi Light Design and Adalsteinn Stefansson.

Graphic design: Rasmus Koch Studio.

note:

this was initially posted on the 2 October but has been moved up to make a more-sensible introduction to the series of posts about chairs posted through October 2017. The chairs were selected because they are important examples from major Danish designers but they also cover all the types of chair in the design museum typology.

These posts on chairs are also an experiment for this site in trying to present more photographs and slightly more information than is normal in a blog to highlight and analyse key features of each design.

Selecting the category a Danish chair will take you to all the posts in the sequence in which they were posted and there is also a new time line to form an index to these posts: