Chairs’ Tectonics

/

This book sets out to establish an acceptable and precise vocabulary so that it is possible to analyse, describe and discuss the design of a chair and, presumably by extension, to apply that same method of analysis to other areas of design. For many people, particularly those not involved professionally in the World of design, the first reaction could be that this is making something that is simple and straightforward unnecessarily complicated to justify an academics expertise - surely a chair is just a seat at the right height, on legs or a pedestal, with an upright to lean back against.

But in a way this is a bit like wine tasting. Initially everyone laughs at the phrases used but actually, if you want to remember a lot of wines, that might be different from each other in only very subtle ways, and you want to work out why you like one and not the other then it soon becomes obvious that an agreed and common vocabulary and a system of description is not just useful but crucial.

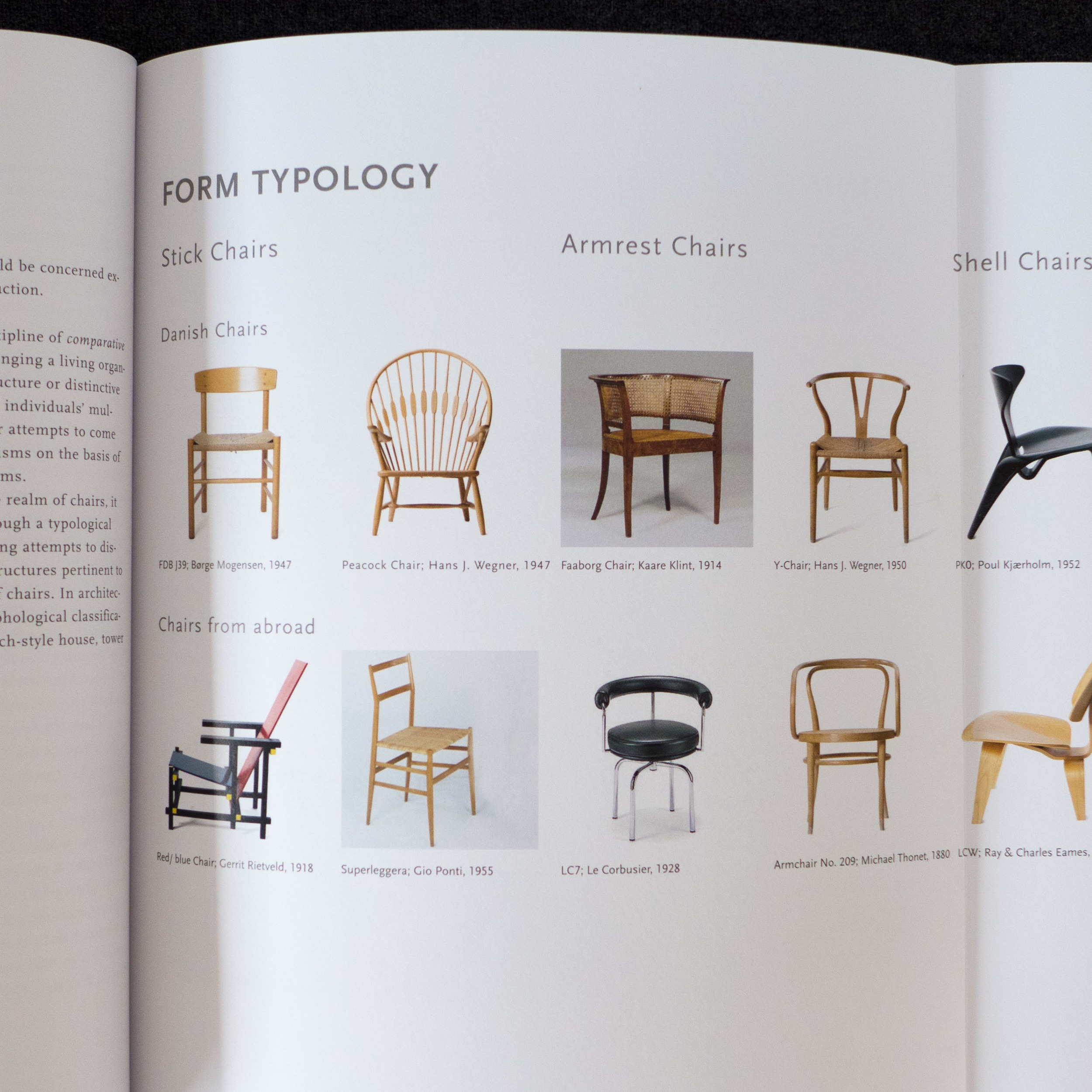

Another clear aim of the book is to emphasise a typology of chair forms … essentially the four main types of chair are here grouped by their construction: the “stick” chair (a chair constructed with a frame); the shell chair; the armrest chair and the “monolithic” chair.

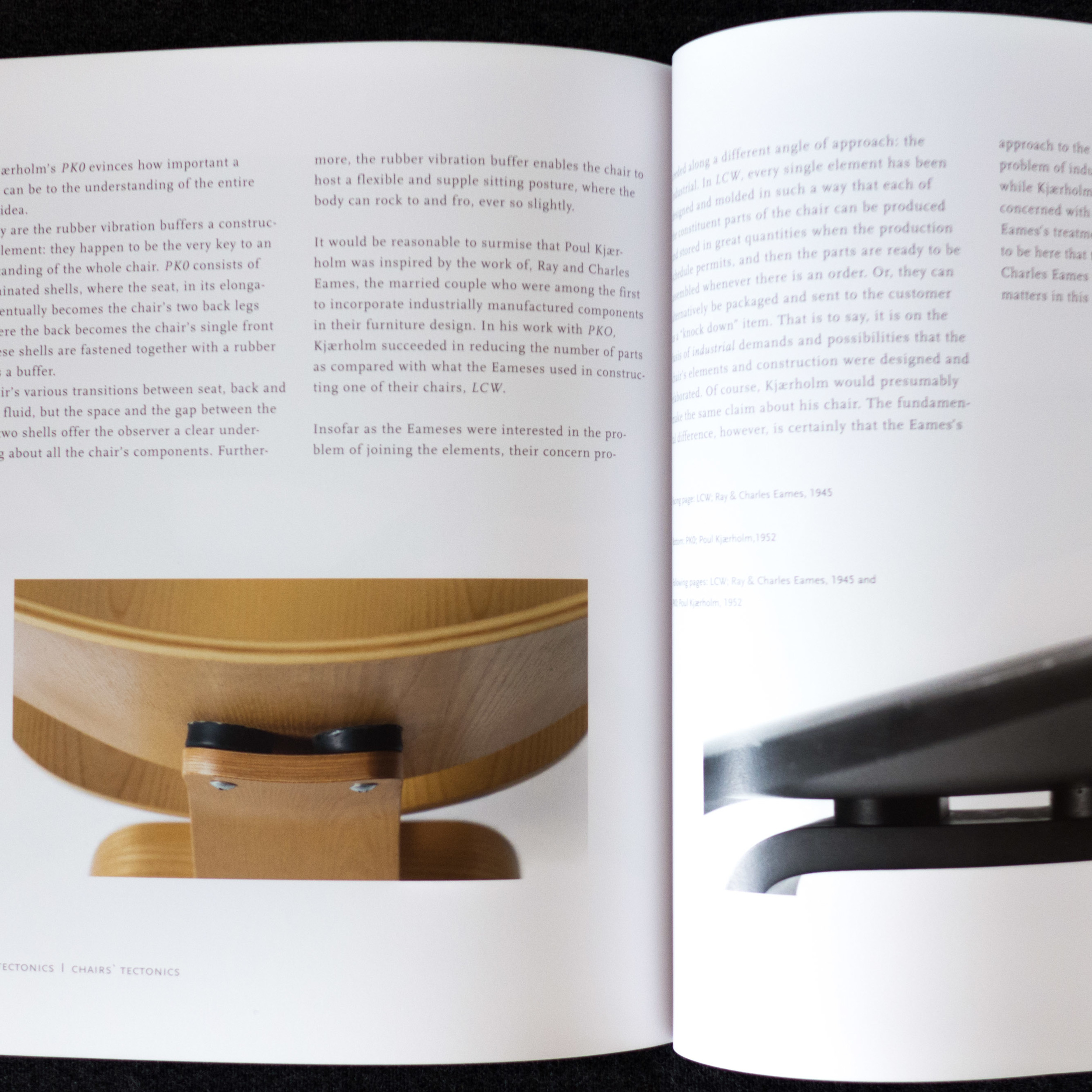

In addition the authors identify three major types of material in their classifications - wood, steel and plastic/composite - and, slightly more difficult to grasp, four modes of joining. This is because joining here is not used in the sense of linking or fixing together but “in forms of mutual relationship” … so here the four types of joining are connection through distance; connection through contact; connection through plaiting and connection through form. This actually begins to make sense once you look at the examples: connection through distance is where a secondary piece, often in a different material, links two major parts of the chair - so the rubber linking pieces used in the PK27 by Kjærholm that links the strut that forms the back and seat frame to the horizontal frame that includes the front and back leg of the chair and provides some give or flexibility to the finished chair. Joining by contact is the most obvious and would include wielding or bolting together separate parts. Plaiting is again more difficult to grasp at first because the image conjured up from the English word is hair but here it refers to a timber joint where each piece is cut back to form tenons that when pushed together form a whole apparently continuous piece .. for instance in the side and front rail of a chair seat. Connection by form is also interesting because although this basically covers moulded chairs, for instance in plastic, when you begin to look at a chair to undertake this sort of verbal analysis you realise that the interesting thing about moulding is that it can but doesn’t always blur the boundaries between one part and another … so in the famous Tulip Chair by Eero Saarien of 1955, where does the seat end and the pedestal start?

In wider use, the word tectonics is more often found in geology and means the study of thrust, slip and faults in the earth’s layers. However, it is clear why the word is used here for furniture because its origins in the Greek word tekton links it to artifice, joining and fabrication - as in the work of a carpenter - and then in the medieval period it was associated with the master builder and then the architect.

Tectonics are therefore the way “in which the chair’s individual parts are joined together.” The book does not discuss scale or proportion … in a very Danish way it is just assumed that those must and have to be related to the elements of the human body. Nor, of course, does it discuss pattern or texture though both can and do have a place in chair design.

In drawing together a range of chairs to analyse and discuss, the book examines a number of chairs designed between 1920 and 2008. It also looks at four distinct threads of north-European design in the 1920s that have become merged and therefore confused … here confused meaning mixed up rather than misunderstood. These threads are … the Danish tradition of style evolved from high levels of craftsmanship; the strong development of a national style in Finland that emerged from the technical exploitation of the native timber, birch; the German school that emerged from the Bauhaus with a preference for the technology of tubular steel and the Austrian development of steamed and bent timber, in a more organic style than Finland, which is exemplified by the chairs produced by Thonet.

Clearly one obvious benefit from looking at a chair in this way is that you begin to see what problems the designer was trying to resolve … whether that is problems of construction or details of style to give the final piece an integrity or consistency… and you can begin to see links between designs that appear to be disparate in date and style … so for instance the Faaborg Chair of 1914 by Kaare Klint and the PK11 of 1957 by Poul Kjærholm.

The deliberately restricted size of the book means that the authors raise a number of ideas but do not have space to discuss them. For instance in the introduction several extremely interesting ideas are raised including a suggestion that designers acquire an ability or skill from their training or education and their subsequent experience in their profession so that they modify and adapt the form or the shape or the details of a design without necessarily being able to explain or analyse what they are doing. There is also an implication that because many furniture designers in Denmark trained as architects they therefore have a different approach to proportions and spatial relationships.

Another interesting but more complicated idea that the authors raise is to describe what they call the subjects “internal connections”: what has changed and continues to change - or evolve - is “the relationship between the chair and the space and the interrelationship among the many different activities the chair is supposed to support.”

One point I wanted to contest immediately was when they talked about symbolism and status they cited the Barcelona Chair of 1929 by Mies van der Rohe and and the PK 22 from 1955 by Poul Kjærholm and suggested they both look back to the Roman curule seat for magistrates. Yet curiously both the 20th-century chairs are low and informal … the sitter almost reclines. As far as I can see, their status comes from their clear expense and not from the posture of the sitter.

It is also interesting that the armrest chair is defined here as not only having arms but generally arms at the level of the top rail of the back. In England there has been a long tradition of constructing chairs with a high back, often high enough to support the back of the head, and then, of course, the arms have to be joined into the uprights of the back as well as being supported by a vertical at the front edge of the seat often, but not always, above the front legs.

The authors also talk about an instinctive response to materials … sight and touch … which helps to explain why some chairs make us want to touch them and walk round them and admire them as well as, or sometimes even instead of, making us want to sit in them. I don’t find the PK22 by Poul Kjaerholm particularly comfortable … for me, personally it is too low and I struggle a bit when I try to get up out of it … but I never tire of looking at it.

Photographs were taken specifically for the book. Many books on furniture only have space for a single rather general image of a piece but here, illustrating the way the authors analyse the chairs in detail, there are particularly good photographs of details … for instance the connection blocks or dampers used in chairs made from plywood and for shell chairs, particularly where there is a moulded-plastic seat and back.

Chairs’ Techtonics was published in 2009 so might not be easy to find in bookshops but it is well worth tracking down if you want to start talking about design in a more serious and in a more disciplined way.

Nicolai de Gier originally trained as a cabinetmaker but graduated from the School of Architecture of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and is now an associate professor, instructor and research academic at the School.

Stine Liv Buur trained as an architect, was a research assistant at the Danish Centre for Design Research and at the time of writing the book was employed by Fritz Hansen.

Chairs’ Tectonics by Nicolai de Gier and Stine Liv Buur

Published in 2009 by The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture Publishers