Torvegade in Copenhagen ... city planning from the 1930s

/This post was inspired by a stroll over Knippelsbro - walking back to Christianshavn from the centre of the city in clear but soft late-afternoon sunlight.

Knippelsbro is the central bridge over the harbour in Copenhagen and I have walked over the bridge dozens and dozens of times - I live just a block back from the bridge - but the sun was relatively low and lighting up the north side of Torvegade - the main street cutting south through Christianshavn from the bridge. The traffic was light so it seemed like a good opportunity to take a photograph.

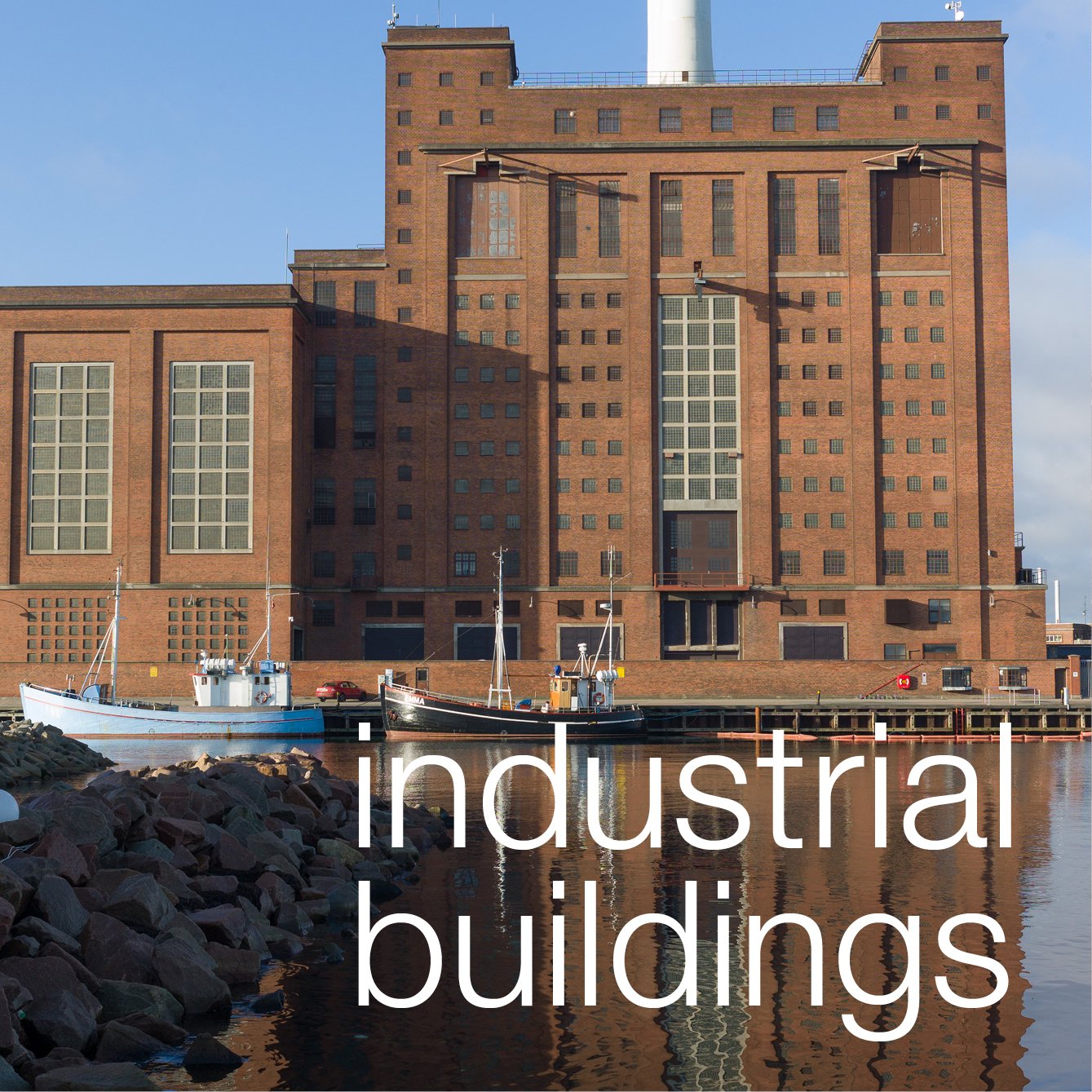

It was only then that it really registered, for the first time, that here is a long line of very large apartment buildings and all dating from the 1930s.

Five large apartment blocks in a straight line - two buildings between the wide road sloping down from the bridge and the canal and then three more beyond the canal before the old outer defences of Christianshavn and the causeway to Amager. Five large city blocks over a distance of well over 400 metres and cutting straight through the centre of the planned town laid out by Christian IV in the early 17th century.

Clearly, this is city planning from the 1930s on a massive scale and not something I had seen written about in any of the usual guide books or architectural histories.

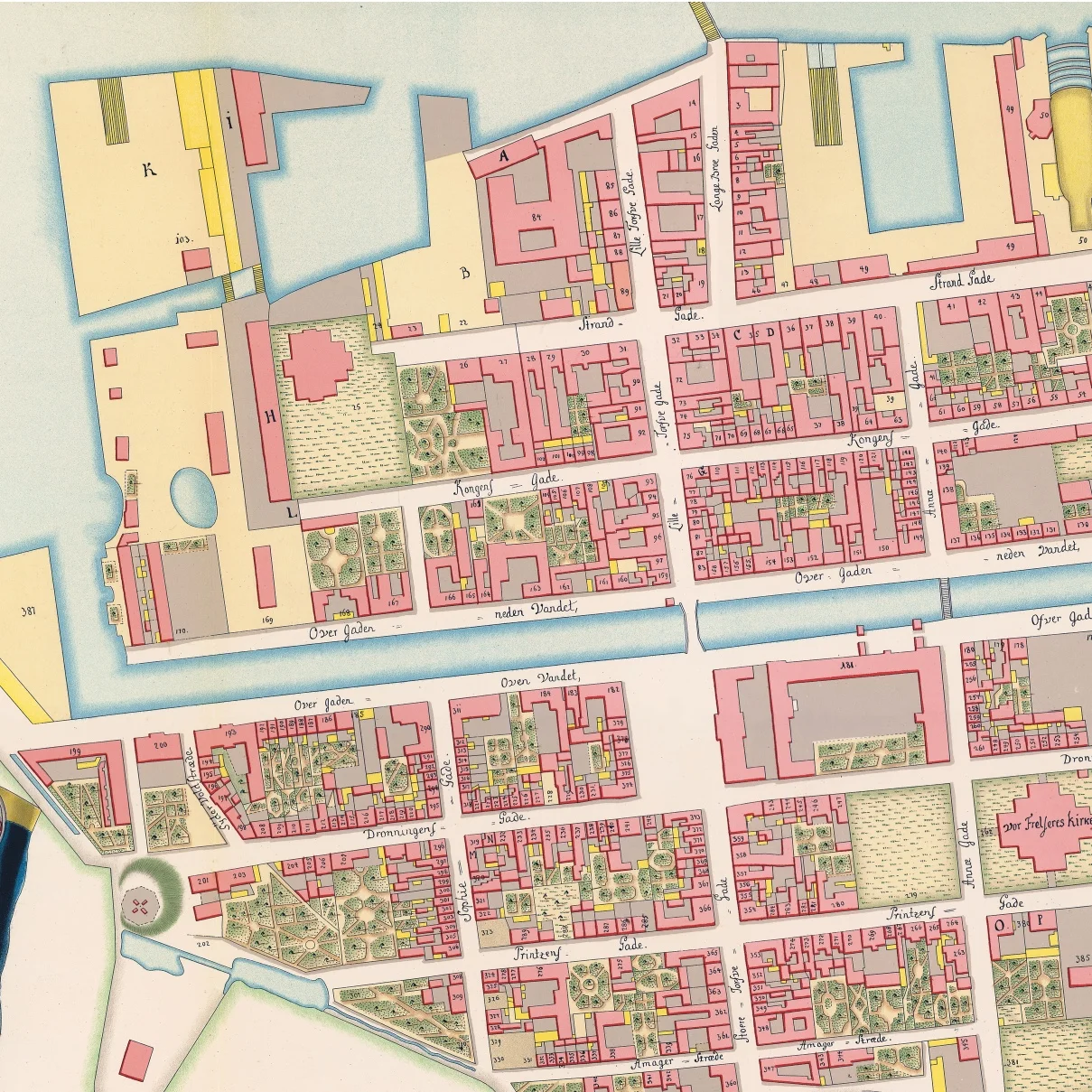

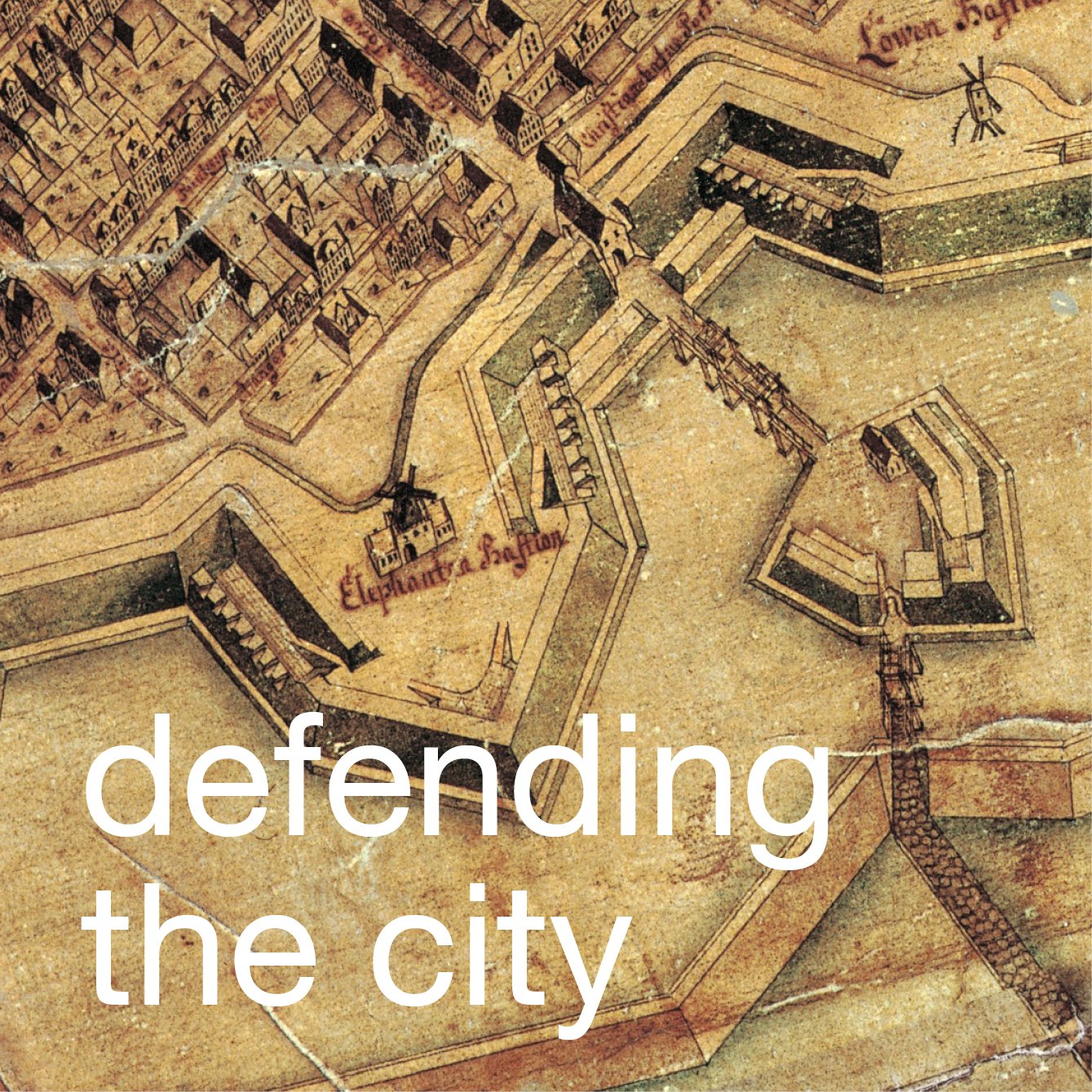

the map of Copenhagen and Amager above dates from the late 17th century and the detail of a map to the right shows Børsen - the stock exchange built in the early 17th century - top left, and the bridge and the north part of Christianshavn in the middle of the 18th century

background

The general history of Christianshavn is well known and has been extensively written about but a brief summary here is necessary to put this work from the 1930s in context.

In the late 16th century Copenhagen was tightly enclosed by defences with an east gate and a west gate only about a 1,000 metres apart and from the north gate to the wharves and jetties along the sea shore - on the line of what is now Gammel Strand - was only about 700 metres - so it was a small city densely packed with houses and commercial buildings around squares and relatively narrow streets.

Just off the shore, about 100 metres from the wharves, was the old castle of the Bishops, by then royal property, and further out, almost 2 kilometres away was the large low-lying island of Amager that was then salt flats and agricultural land with farms and several small settlements.

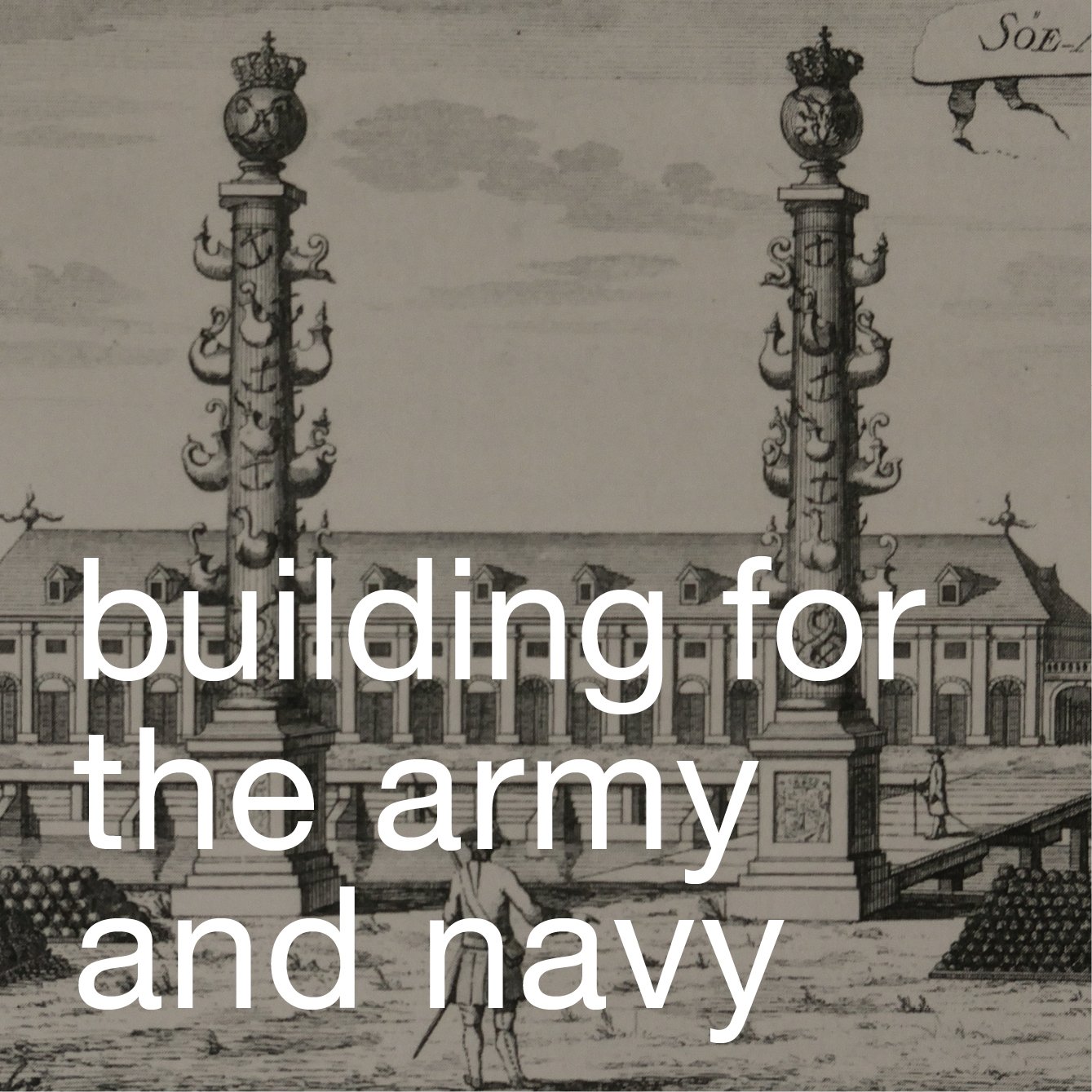

In the decades around 1600, Christian IV instigated the construction of a massive new harbour with a line of defences in a great arc curving out into the channel between the city and the island of Amager with naval ship yards and protected moorings for the navy to the east and, to the west, within the defences and opposite the existing city, a new planned town that is still at the core of Christianshavn.

There was just one main bridge over the harbour, between Christian’s new Bourse and the new town, roughly in the position of the modern Knipplesbro although the exact alignment of the bridge has been changed slightly each time it has been rebuilt.

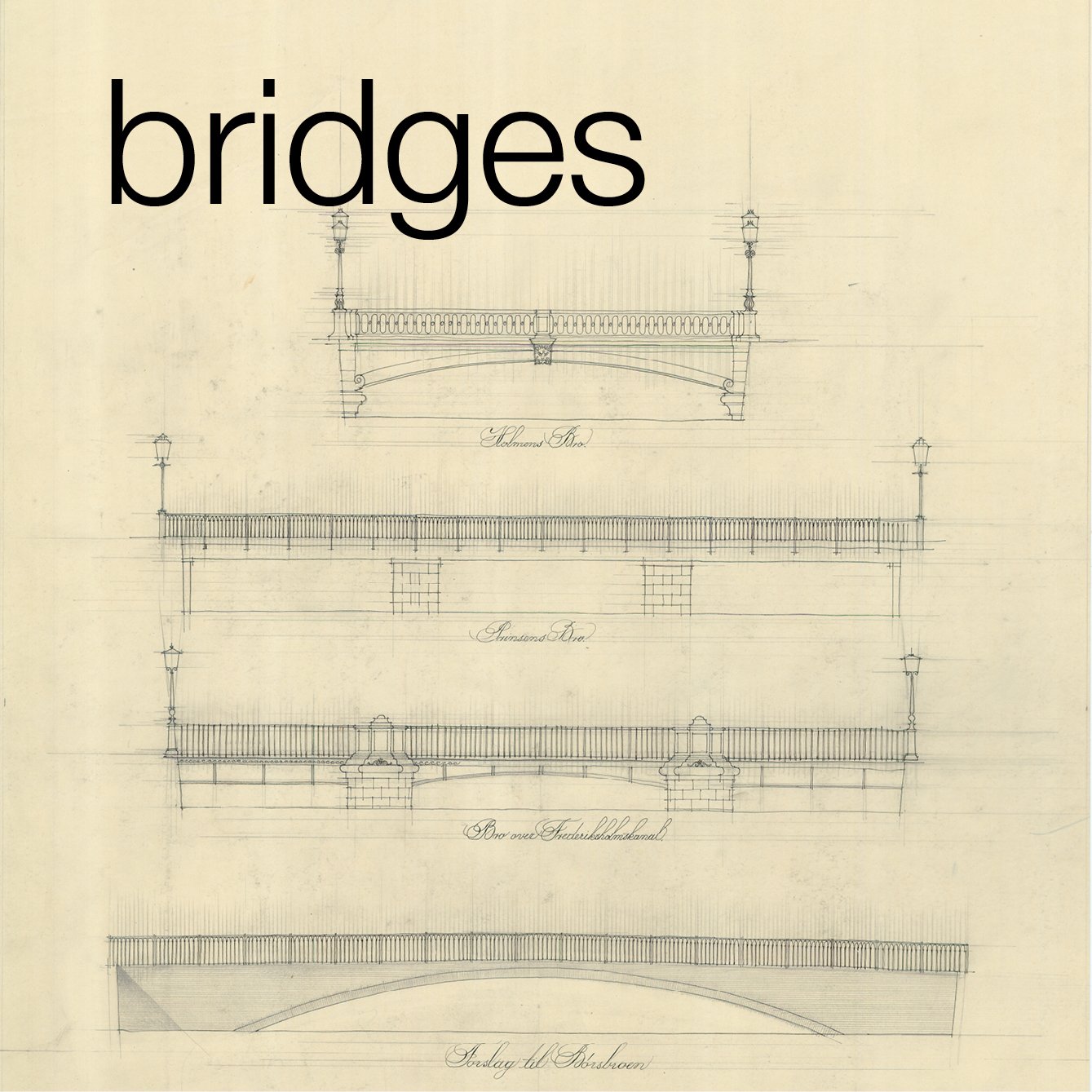

Work on the present bridge began in 1934 with the construction first of a temporary bridge - so that the old bridge could be demolished but traffic could still continue to cross to Christianshavn - and then, over about three years, a large and distinctive new bridge, with two copper-clad towers, was built. Work on the bridge was completed by 1937, although the bridge was not officially inaugurated until 1947, but it should be seen as part of a major plan by the city for a redevelopment of Christianshavn that included the rebuilding of Torvegade.

rebuilding in the historic city ....

In Copenhagen, as in most historic cities in Europe, extensive rebuilding or redevelopment over more than a city block was difficult or at least restricted because of the complicated and fragmented ownership of land. In Europe in the past there have been exceptions to a general rule of piecemeal redevelopment in major cities and towns - the rebuilding of Paris under Haussmann in the middle of the 19th century being the example most often cited - but generally, even if there is a disaster such as a major fire or destruction in war, land was still divided up between various owners.

New developments, on any large scale, are easier on new land or land with few buildings and this is particularly obvious when it was part of an expansion outwards of a city as a response to a marked increase in the population. For Copenhagen the obvious examples of such expansion over relatively open ground includes first the new area to the east of the old city, including the royal palace and the Marble Church, that was laid out in the 18th century; then massive new work on the line of the old defensive embankments in the 1870s that transformed the city after the defences were dismantled - so the streets and squares beyond Nørreport and the buildings above and below the City Hall around 1900 - and of course the expansion of the city out into new areas of Nørrebro and Vesterbro and to the south on Amager itself including the apartments of Islands Brygge, south of Christianshavn, on land claimed from the sea in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Before 1900 there were some extensive changes to the street scape within the old part of the city itself so, for instance, Højbro Plads was opened up to form a new public square close to the castle when old houses were lost in the Great Fire of 1795 and not rebuilt. A much larger public square was created when the late medieval town hall was demolished and a new town hall built in 1805 on the west side of Ny Torv or New Square - rather than in the centre. Large new buildings were constructed for the University around the cathedral, including a large new library completed in the 1860s, that must have been on the site of older houses and there was the creation of new streets and very large new buildings - over the site of notorious slums that were then a red-light district - in the area to the south of the King’s Garden around Gammel Mont when Christian IX’s Gade was cut through as a wide new road in 1906. But none of these developments stand out now as intrusive or even as obviously disruptive of the historic street pattern unless you study historic maps.

Of course, from the late 1940s onwards we have become increasingly desensitised to the scale of inner city ‘regeneration’ in many European cities - so, for instance, with the massive commercial buildings and wide new inner-city roads that were cut through east of the main railway station in the centre of Stockholm - but generally, in the historic centre of Copenhagen, in the area within the line of the old defences and in the 18th-century part of the city around the royal palace, rebuilding has been limited to single plots or at most a block. The only obvious large-scale modern redevelopment in the historic centre is the area of well-known slum clearance around Borgergade that was undertaken immediately after the war for the construction of the Dronningens housing scheme designed by Kay Fisker and C F Møller and Sven Eske Kristensen that was completed in 1958.

However, in terms of scale, and because of the number of historic buildings that were demolished, the redevelopment of Torvegade in the 1930s had a considerable impact over a large area.

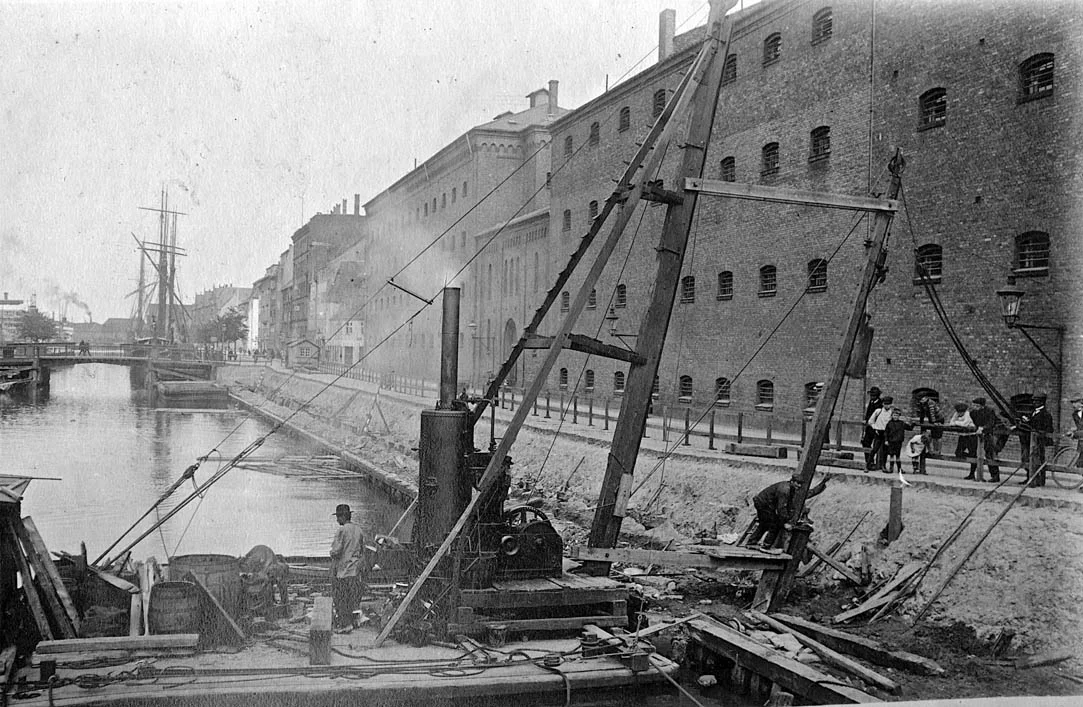

the photograph above was taken at the north end of Torvegade before the bridge was rebuilt and is looking towards the harbour - the ornate gable seen in the distance beyond the trams is an apartment building from about 1900 that is on the far side of the harbour and survives at the south end of Børsen

to the right, the photograph shows Torvegade from the new bridge looking south with the first of the new apartment buildings at the centre ... the historic buildings on either side of the road down from the bridge were subsequently demolished and are now the sites of large modern post-war office buildings shown in green on the map below

a map from the middle of the 18th century shows Torvegade running north south down the centre of Christianshavn but at that stage the bridge over the harbour was not on the line of Torvegade but one block to the east. The open space at the centre of Torvegade was the market that gave the street its name.

Around the south end of the old bridge thirty five or possibly more old brick or timber-framed house were demolished and between there and the canal thirty six historic building were demolished. Beyond the canal a prison, the “women’s house of correction” was flattened - now the block where the building with Christianshavn library stands - and beyond, between the square and the outer defences, another 40 or more old buildings were demolished including, close to the defences, some striking timber-framed buildings with galleried courtyards. In fact the whole of the street line on that north side of Torvegade, and including the old guardhouse itself from the south gate to the city, were moved back 14 metres to create a much wider and much grander approach to the city from the south.

There is perhaps one key to the reasons for the scale of this redevelopment - above and beyond of course a general aim to provide more housing - and that was to provide a better approach into the city from its new airport. It is not quite so obvious now, because most people arriving in Copenhagen at the airport come into the city on the metro or by train, but actually in the 1930s Torvegade was the main and the direct road out to and back from the city airport less than 6 kilometres south of Christianshavn and the new airport terminal, set back on the east side of the road and designed by Vilhelm Lautizen, was completed in 1939.

So, if Torvegade and Amagerbrogade, its continuation south, was the route from the new airport terminal, that included a wide modern new bridge to take visitors right into the centre of the capitol at Børsen and the parliament buildings?

If so, then it would appear that the extensive renewal of Torvegade was conceived, in part, to mark or establish the sense of a modern capital city … the appeal of progress … to move Copenhagen forward into a new modern age.

If that sounds like fanciful conjecture there are two drawings in the collection of architectural drawings of Danmarks Kunstbibliotek by Frode Galatius that are dated April 1938 and show the street frontage of a new apartment block that was about to be built just to the south of the defences on the east side of Amagerbrogade … the continuation of Torvegade towards the airport. The first (a perspektiv af facaden mod Amagerbrogade, 1938) shows two smart young women talking on the pavement opposite the new block, both wearing fashionable and elegant suits, one with a fur draped across her shoulders and the other with a small dog on a lead. On the other side of the street is the end of the new block with a smart store across the ground floor and balconies to the five storeys of apartments above and there is a swish open-topped sports car heading out towards the airport and above, to emphasise the point, a plane that has clearly just taken off from the airport. The second view (b persptiv fra krydset Amagerbrogade/Amager Boulevard, 1938) is looking north towards Torvegade and the city, and shows a smart yellow, stream-lined tram heading out towards the airport, cars heading in and out and again a aeroplane ... here heading down to land at Kastrup.

an earlier bridge looking from Christianshavn towards the city. The buildings to the right survive but the buildings seen here beyond the bridge to the left were demolished in the middle of the 20th century and this is now the site of the national bank designed by Arne Jacobsen. Clearly one practical reason for building a new bridge was to take the causeway higher so more ships could pass between the north and south parts of the inner harbour without having to raise the bridge and hold up the road traffic

Knippelsbro - the bridge

Knippelsbro is at the centre of the harbour and a bridge here - or one of the earlier bridges on this site - was the main way to cross from the old city to Christianshavn. Originally it was known as Store Amager Bro (or Great Amager Bridge) and then Langebro or Long Bridge and from about 1700 as Christianshavns Bro (Christianshavn's Bridge)

The more popular name comes from one Hans Knip who was the bridge keeper in the middle of the 17th century. From the start the bridge had to be raised to let tall ships through - so presumably Knip collected tolls. His house was known as Knippenshus and, later in the 17th century, the bridge became known as Knippensbro.

Completed in 1937, the present bridge was designed by Kaj Gottlob and built by Wright, Thomsen & Kier with Burmeister & Wain whose engine works were just to the west of the bridge and whose ship yards were to the east at Refshaleøen.

The copper-clad towers and the long wide arc of the central section, that can be raised to let tall ships through, are a dominant and now, perhaps, the iconic feature of the inner harbour. Is it a step too far to imagine the citizens of Copenhagen dashing over the bridge in cars and on trams on their way out to the new airport as one potent symbol of a new modern age in the 30s? And, of course, the apartments as a fashionable place to live?

Knippelsbro from the Christianshavn side. The apartment building dating from c..1900 is at the south end of the 17th-century Bourse and can be seen in the historic photo above that shows the historic buildings that were demolished when the new bridge was constructed

1 Bartholomæusgården

The first apartment building at the south end of the bridge is Bartholomæusgården, designed by the architects Arthur Wittmaack (1878-1965) and Vilhelm Hvalsøe (1883-1958) and completed in 1933. The main front is to Torvegade but the building returns down Strandgade on the city side and down the first part of Wildersgade to the south. The roof returns down the Strandgade front as a form of hip that is important because it gives the side facade the sense of being rather like a pavilion because, with the building line between the harbour and Strandgade set back, the apartment building itself does close and narrow the view line on the approach to Torvegade.

Although all the apartment buildings down Torvegade have ridged and tiled rather than flat roofs, the slope of the roof of Bartholomæusgården flattens or flares out towards the eaves reducing its impact and dominance and, in fact, the view of the the buildings in line manages to suppress the visual impact of those roofs so that the initial impression is of large, square, flat-roofed blocks.

The main front of Bartholomæusgården has narrow, square bay windows but, as with many buildings in the city, both earlier and later, the bays only start at second-floor level so they are cantilevered out over the street. In part that keeps the pavement free but also the bays are high enough so they do not impede passing traffic if it cuts in too close to the pavement.

The bays have continuous glazing to the front and sides - a variation of the wrap-around window of the period - and were only possible with good engineering - and presumably with good steel - supporting the weight of the windows and walls above. The building does not have projecting balconies but there are what are sometimes called Juliet balconies with full-length windows or French windows that open inwards and the lower part with balustrades flush to the wall line.

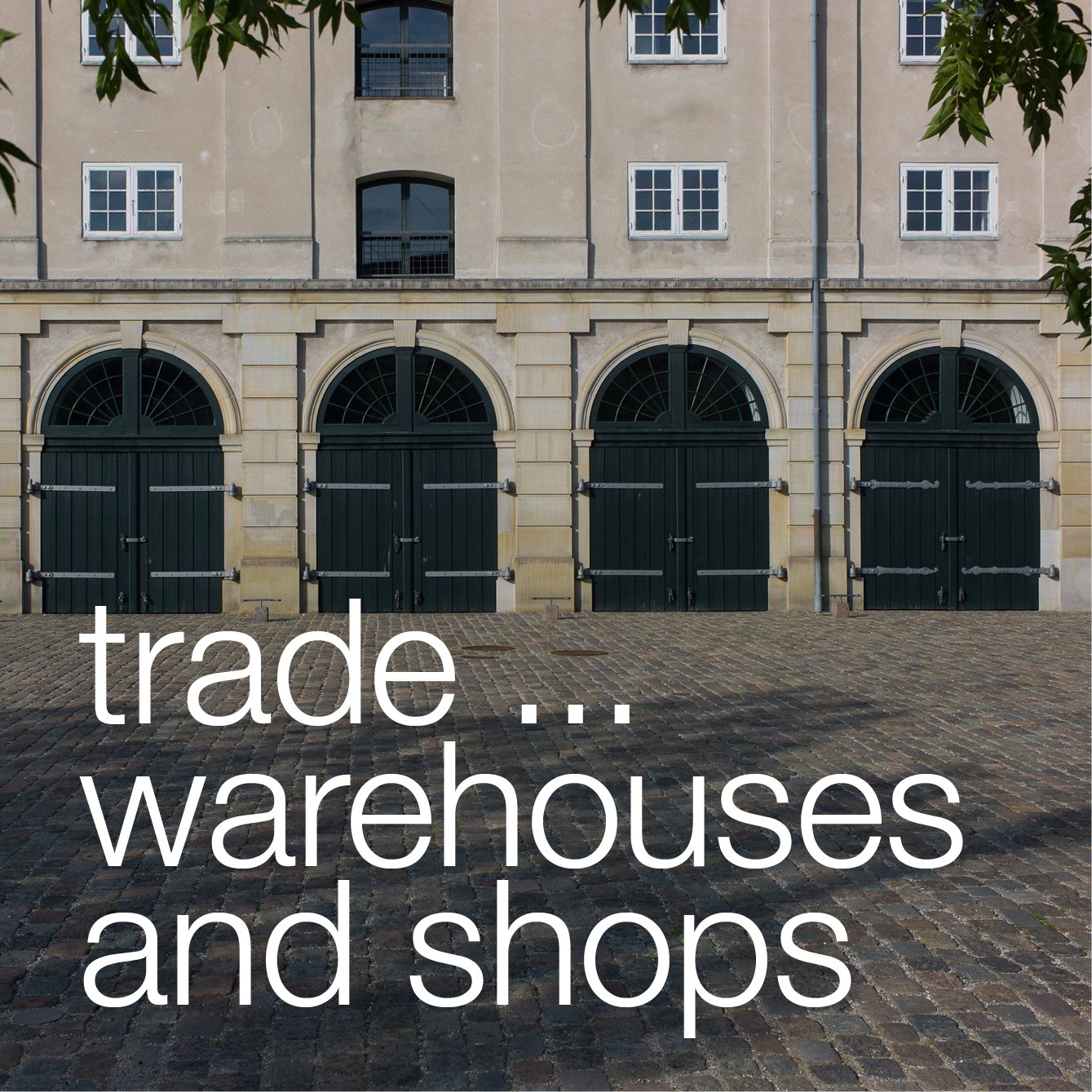

All the ground floor is commercial space so, from the start, Torvegade was seen as a major shopping street as well as a main route through the area. 'Torvegade' in English is Market Street.

2nd apartment building

Designed by Bent Helweg-Møller (1883-1956) the second apartment building was completed in 1933. The three facades - the street fronts of the block - are different, and in many ways this is the least successful or rather the least coherent design of the five buildings along Torvegade although Møller was a prolific and successful architect whose works include the Berlingske print works in the city ... an iconic building of the 1930s.

Towards Wildersgade the facade of this apartment building is stark, almost severe and the angled corner is interesting but ultimately weakens the design of the block as a whole. Again it is a feature found in many buildings in the city as a way to transition from one street frontage round the corner to the next street and can form an interesting opening out of a cross roads when all four buildings do it but here, as the only building that uses the device, it simply undermines the solidity of the block.

To Torvegade there are balconies but only to four central columns of windows leaving the outer sections again looking rather stark.

The most complicated design is for the return facade down the canal where there were larger and more expensive apartments. Here the wide end bays are set back but with wide balconies, the full width of the building bay, coming out to the facade line and these bays of the building extend up to form what appear to be almost flanking corner turrets and at the sixth floor or roof level there is a large canopy cantilevered out over a roof terrace.

The windows to the centre, eight to each floor level, are again severe, without architraves and with the window frames set forward on the facade line taking out all shadow, and the windows are not regularly spaced so, overall, the front to the canal has a sort of grandeur but is visually rather restless and the design unresolved.

Again there are shops or commercial properties at street level but also offices across the first floor. The commercial space at the corner, with its doorway facing the canal, is now a cafe but it was a savings bank and has amazing bronze outer doors. These are on pivots rather than hinges and swing back during the day to form an entrance porch. There appear to be no lock plates or handles so presumably, as added security, they can only be unlocked and opened from the inside. The message from the large central medallion, formed when the doors are closed, seems to be that the good Copenhagen girl, with her sensible clogs, is not impressed by the sailor with his bag of money so he should put his cash into the savings bank to win her over!

As with Bartholomæusgården, all the old buildings along Torvegade were demolished along with the first buildings back down the side streets. Fewer houses along Wildersgade were demolished than along the canal frontage so the building is irregular and has a rather tight courtyard and there seems to be no attempt to create any symmetry or consistency in the arrangement of the plans of the apartments … a feature of planning that was becoming more and more common so here any symmetry is external rather than in terms of the internal arrangement.

On Wildersgade, running back from Torvegade, both this building and Bartholomæusgården to the north have facades that are set back further than the street line of the historic buildings further into the block so this would suggest that planners were considering a much more extensive clearing of historic buildings behind Torvegade for wider streets running back into Christianshavn.

looking down Wildersgade from Torvegade ... the setting back of the street line of the apartment buildings on either side would suggest that the plan was to demolish more of the historic buildings further back and lay out wider streets through Christianshavn

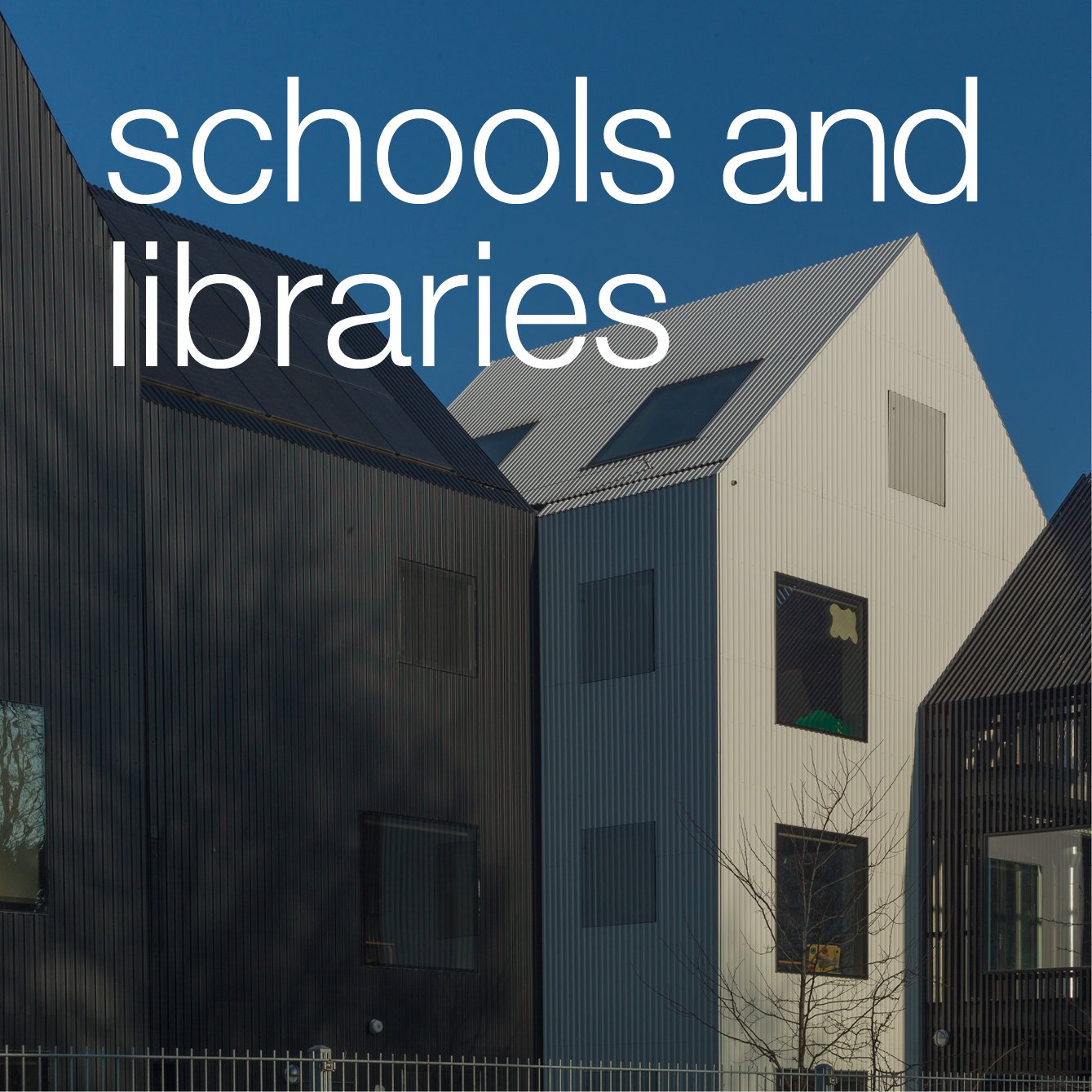

3 Lagkagehuset

This is the most striking and the most well-known of the five apartment buildings - in part because it is now seen by so many people arriving in the area on the metro as the Christianshavn station is in the square in front of the building. The library for the kommune is here on the first floor overlooking the square and there is a popular bakery at the canal corner although the company takes it's name from the nickname for the building rather than the building taking it's name from the bakers.

The apartment building has prominent bands of white at the level of the windows and wide continuous bands of yellow plaster below the windows so the building, quite soon after it was finished, became known as the the layer cake house or Lagkagehuset. When Ole Kristoffersen and Steen Skallebæk opened their bakery here in 2008 it must have been an obvious name for their new company.

the north side of the prison towards the canal

There had been a large prison or house of correction for women on this site that had been rebuilt several times with the last building around two separate courtyards. The whole block was cleared in the 1930s and this is the only building of the five apartment buildings along Torvegade that is a complete square around a large courtyard with four good facades.

Architectural details are good with interesting lettering and with the use of high-quality materials with marble facing around the ground level and good brass doors and architectural fittings.

The architect was Edvard Johan Thomsen (1884-1980) who had graduated from the School of Architecture in 1914 and was secretary of the Free Association of Architects and became a professor of architecture in 1920.

4 Salvatorgården

Salvatorgården was designed by Arthur Wittmaack (1878-1965) and Vilhelm Hvalsoe (1883-1958) and is built around three sides of a courtyard with fronts to Prinsessegade, Torvegade and Dronningensgade.

On the street frontage there are projecting square bays for the apartments on the second floor and higher but here with windows only to the front and to the south side of the bays and there are distinctive windows at and wrapping around the corners of the block.

One distinctive and more unusual feature of the building is that the first floor towards Torvegade has a continuous balcony that forms a canopy over the shop fronts on the ground floor.

this photograph from the 1930s shows Lagkagehuset and the two blocks to the north as constructed but here the historic buildings along Torvegade have only just been demolished and it shows clearly just how narrow the street was and just how close the tram tracks were and how much of the width of the street they took up. Presumably one important reason for making the street so much wider was so that the tram tracks could be moved to the centre so that when the trams stopped for passengers to get on and off, other traffic could continue to move between the trams and the pavement

5 Ved Volden

Ved Volden - just inside the ramparts and the water of the defences - is the largest and perhaps the most problematic site of the five along the north side of Torvegade with an irregular shape defined on the south by the angle of the substantial and historically important defensive bank. Several arrangements of enclosed courtyard were proposed including one with a zig zag line of blocks following the angle of the embankment.

The architects were Tyge Hvass (1885-1963) and Henning Jørgensen (1883-1973).

One drawing by Hvassin in the collection of Danmarks Kunstbibliotek - 15229 a-ah - shows a block set across the courtyard - running straight back from Torvegade - but the blocks in that proposal have penthouses with flat roofs for a sixth floor with the apartments at that level set back behind a railing to form a continuous balcony for a remarkably modern look. It would suggest that architects saw the redevelopment of Torvegade as an opportunity to be innovative - where they could try out new ideas on large and prominent buildings.

In the design as built, there is a large L-shaped block with shops at street level along Torvegade and five storeys of apartments above that returns along Princessegade with a long separate detached block on the third side of a large courtyard that is open on the south side towards the defences. Both buildings have simple but prominent pitched roofs.

The housing scheme was completed in 1938 and now has 177 apartments.

One notable feature is that each entrance lobby is decorated with a mural painted by the American-Danish artist Elsa Thoresen with her husband Vilhelm Bjerke Petersen in 1939.

the historic photographs of Torvegade from the south show the narrow road before the redevelopment of the 1930s. the buildings on the left survive. The building line on the right and the 17th-century guardhouse that was originally just inside the south gate of the city were moved back by 14 metres.

The building immediately beyond the guard house may look from the street front as if it dates from the 19th century but in fact the courtyard behind had amazing open galleries in timber that were surveyed and drawn just before they were demolished

the square at the centre of Torvegade looking south from the canal ... the prison that was on the site of what is now Lagkagehuset with the local library is on the left side of the view and the apartment building on the right was demolished when Torvegården was built

6 Torvegården

There is a sixth apartment building that should be considered as a part of this Torvegade re-development in the 1930s although it is on the other side of the road, on the opposite side of the square to Lagkagehuset, with fronts to the square and to the canal, and it is just slightly later so was the last of the apartment buildings to be constructed.

Torvegården was designed by Viggo S Jørgensen (1902-1981) and Sven Gunnar Høyrup (1897-1977) and was completed in 1940 or 1941. Høyrup was a pupil of Edvard Thomsen so may also have worked on the designs for Lagkagehuset.

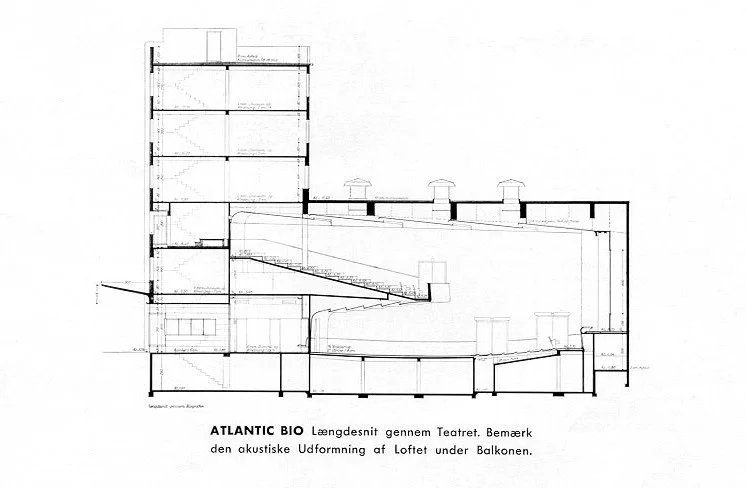

There have been extensive alterations to Torvegården as originally it included an 800 seat cinema - the Atlantic Bio Cinema that opened in February 1941. The cinema closed in September 1976 and that space is now a large supermarket although at one point there was a proposal to restore the projection rooms and open a new cinema in what had been the first-floor gallery.

With a large cantilevered canopy towards the square; a clock set into the corner with square faces; the balconies and the white plastered facades, and with the style of the interior of the cinema, the building came perilously close to slipping from Functionalism into Art Deco.

the original front towards the square - with the canal and the metro station to the right

the ground floor of the cinema and commercial space at the canal corner of the building are now a single large supermarket

note:

Jørgensen designed an important housing scheme at Sundparken on Amager that was completed in 1940.

general introduction to apartment buildings in Copenhagen from the 1930s