Arne Jacobsen Architect & Designer, Poul Erik Tøjner and Kjeld Vindum, Dansk Design Center 1999.

Normally reviews here are for books that are still in print but this is a really good general introduction to the buildings and the furniture and fittings that were designed by Arne Jacobsen and it can still be found second hand.

It was published by the Danish Design Center to coincide with a retrospective exhibition.

The format is interesting with the pages 240mm wide by 229mm, when bound and trimmed, so a double-page spread is almost a double square.

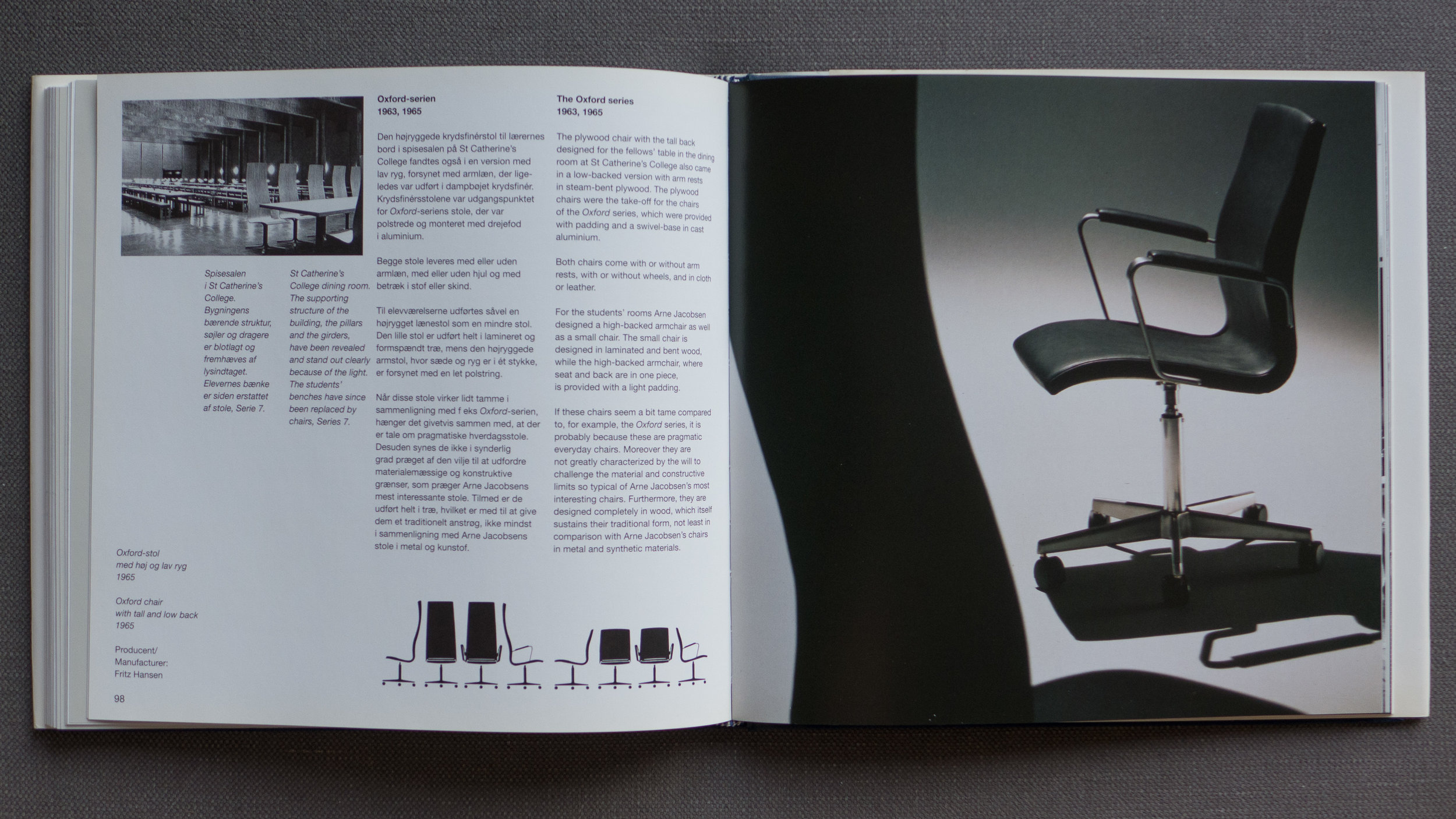

Those double-page spreads are used well with most covering a single building or single theme and with the use of whole page images and the use of bleed off to good effect.

There is a good use of black and white photographs including historic images. Of course black and white photographs were more prolific in book production to control print costs but black and white images can also have distinct qualities in high lighting shape and form where sometimes colour can be a distraction and for many buildings black and white images heighten the drama of a space … often by bringing stronger emphasis to lines and edges.

All text and captions are in both Danish and English but used cleverly in columns with captions either stacked in a singe narrow column or actually divided to the margins of facing pages if appropriate so this is fairly subtle and you rarely have the impression that you are reading half a book.

There are a number of interviews that are spread through the book but distinguished by being printed on a pale grey paper. These provide a real insight into the working practice of Jacobsen from people who worked with the architect and many who worked with him over many years and on many projects.

These include Erik Olsen and Ove Hansen - who had worked with Jacobsen on the lighting produced by Louis Poulsen - Hansen was the chief engineer for Louis Poulsen - Verner Panton who worked in the Jacobsen design office - M Folmer Anersen who was the engineering consultant on several projects and Henning Simony who worked for Novo and collaborated with Jacobsen on the buildings he designed for the company.

Sandor Perjesi was a sculptor who worked with Jacobsen on the full-sized plaster models for the chairs for the SAS Royal Hotel and Peter Lassen worked on project development with Fritz Hansen and there are interviews with the men who worked with Jacobsen on the design and construction of St. Catherine's College in Oxford including Lord Bullock and Jack Lankester from the university and Knud Holscher who managed the project on site in Oxford.

There are some fascinating revelations that focus on Jacobsen's approach to design and work methods so for instance building projects were presented to clients with beautiful water colour drawings - several books of Jacobsen's water color paintings and studies from nature have been published - but furniture designs started with a small and often very rough sketch and then evolved through a series of models from the workshops of the companies that were then edited by Jacobsen and sent back for revisions … often many and many small revisions.

Niels Jørgen Haugesen, worked with Jacobsen on a chair design using plaster models in the same way that Jacobsen worked when he was designing The Egg and The Swan. He makes the brilliant point that Jacobsen taught him "about form; about the link between eye and hand - about seeing a piece of furniture both as sculpture and a functional object." (see page 108)

In several interviews it is stated that Jacobsen could be very critical and was very certain about what he wanted but was usually right and several designers make the point that few of his designs were unique or revolutionary in their initial conception but that he was very clear about how a form or a technique could be developed and how in that process he imposed his specific and personal aesthetic. It is also clear that, although many might assume that he completely controlled projects from his design office, that was not done by doing everything himself or by not letting things go but by either inspiring or demanding loyalty. Perhaps on major projects like the SAS Royal Hotel or the National Bank in Copenhagen, that was the only way that so much could be achieved in a relatively short time … was Jacobsen like Leonard Bernstein … a composer but also a great if difficult conductor?

The book ends with an interesting text from an interview with Arne Jacobsen that was published in the newspaper Politiken in February 1971 … interesting because Jacobsen rarely talked at length about his work and rarely talked about theory or aesthetics and this was published just a month before his death.

There is also a short bibliography and a useful chronological list of works that incorporates basic biographical information.