We don’t do it like that here .... Swedish stoves

/Swedish stoves, sometimes called masonry stoves, or in Swedish Kakelugn, are still found and still used in older houses and in larger, older apartments throughout the country and in some apartments and larger houses in Copenhagen and elsewhere in Denmark - in fact in various forms these stoves are found throughout the Baltic region - basically anywhere that gets really cold in winter.

There can’t be many in England although I guess some may have been brought over by Scandinavians who moved here, or there may even be Kakelugn that were imported by English people who have lived in Scandinavia and, on returning home, realised they could not survive happily through the winter without one.

In England, of course, some houses still have open fires that can burn coal or logs and this is the land of the Aga - if you believe some interior design magazines all middle-class English home owners either have an Aga or if they don't have an Aga they want to buy an Aga.

Swedish stoves use similar methods to the cast-iron cooking range, with a relatively small enclosed fire box, to improve the way the fuel burns, but obviously without hot plates and food ovens for cooking … these stoves were and are just room heaters and houses or apartments had normal ranges or ovens in the kitchen for cooking.

Swedish stoves are built with bricks so they are covered with tiles - some with plain tiles but many with beautiful and expensive moulded or decorated tiles - and the stoves are often extremely elegant, designed to be used in the poshest and most polite of rooms.

Basically the principles behind a Swedish stove are simple to understand.

An open fireplace of the English type throws heat out into the room but can be pretty inefficient because much of the heat from the flames is lost with the smoke that goes up the chimney and, generally, the chimney itself is small to help the fire draw so, even in the flue, not much heat is retained.

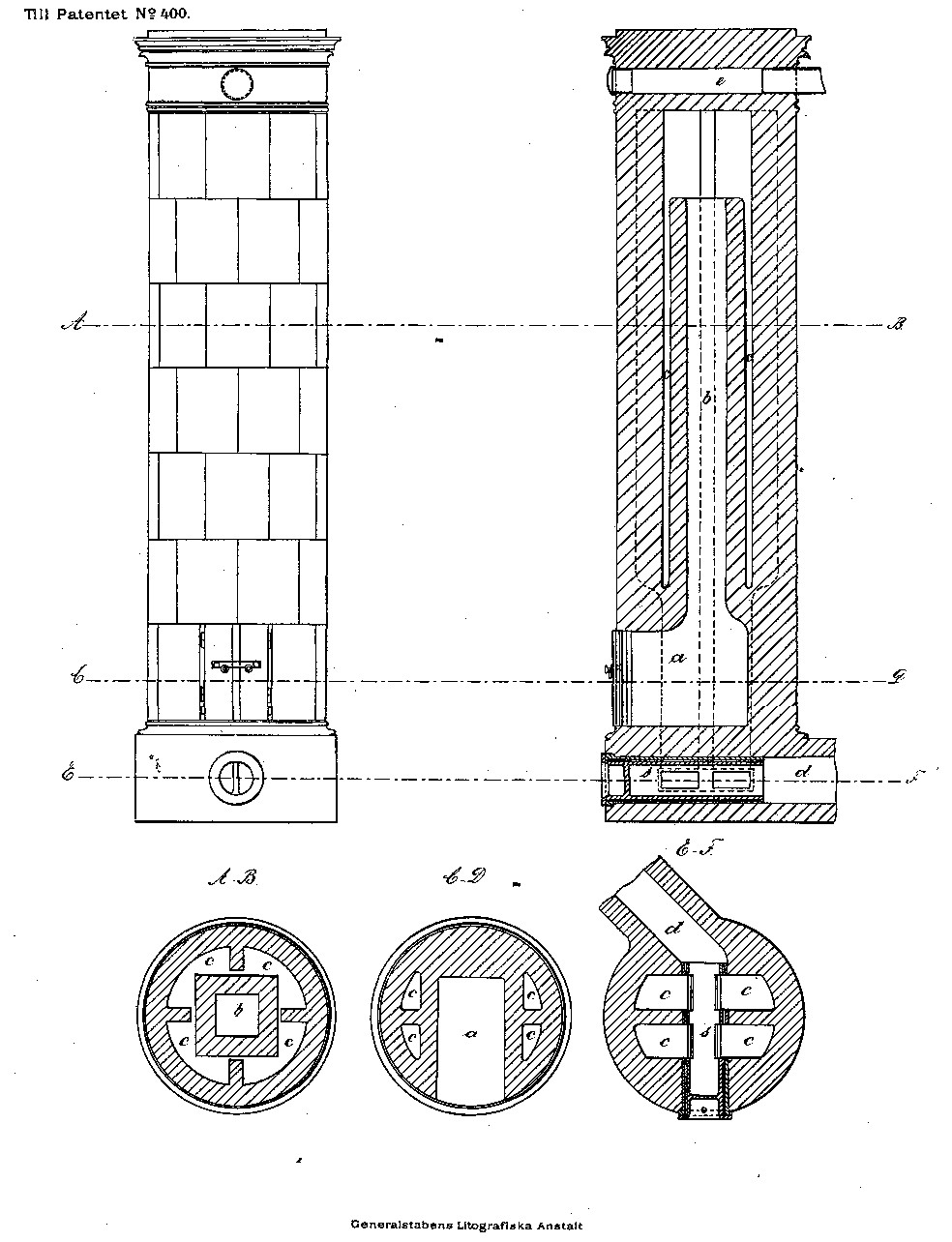

In contrast, Swedish stoves are substantial, built with shaped bricks with the joints between the bricks sealed with clay. In the lower part there is a fire box where wood burns at a very high temperature. Gases (and heat) can go straight up the chimney but if a baffle is closed then the hot fumes are redirected through a number of flues around the outer edge of the stove before finally being drawn out through the chimney. This means that the bricks themselves warm up quickly and retain the heat which then slowly radiates out to warm the room. The tiles also help retain heat but rarely get too hot to touch. Other features found are pipes or channels sometimes built in below the hearth to bring a draught of fresh air into the firebox, to make burning more intense, and there are usually small hatches in the side of the stove for access to clean out any soot or resin from the fuel that has built up in the flues.

The main advantage of this form of stove is that, once it gets up to temperature, it continues to give out heat as the bricks cool slowly over a period of ten or twelve hours, long after the fire itself has died down. That means the stove does not have to burn continuously to heat the room but at best only twice a day - in the morning to heat the room through the day and in the late afternoon or early evening to bring the bricks back up in temperature to heat the room through the night.

The design of this form of stove is credited to Carl Johan Cronstedt who was born in 1709. He was an architect and engineer and a member of the Royal Academy of Science in Stockholm and he set out deliberately to redesign the traditional wood stove so that it burned fuel more efficiently. In fact his design was said to be eight times more efficient than an ordinary wood stove. His designs were published in 1767 in his book On a new installation of stoves for firewood saving.

If the stoves were set on a brick or stone plinth they could even be built into timber-framed houses - the only problem then being the weight - and by the 19th century, large houses of the middle and upper classes could have a stove like this in the corner of every room.

This is a good example of design responding to both ecological pressure and social pressure ... by the late 18th century, with large areas of the countryside cleared for agriculture, timber for fuel was less plentiful particularly in towns and houses were getting larger, so more difficult to heat, but people expected higher levels of comfort. Somehow sounds familiar.