concrete and steel in the 1930s

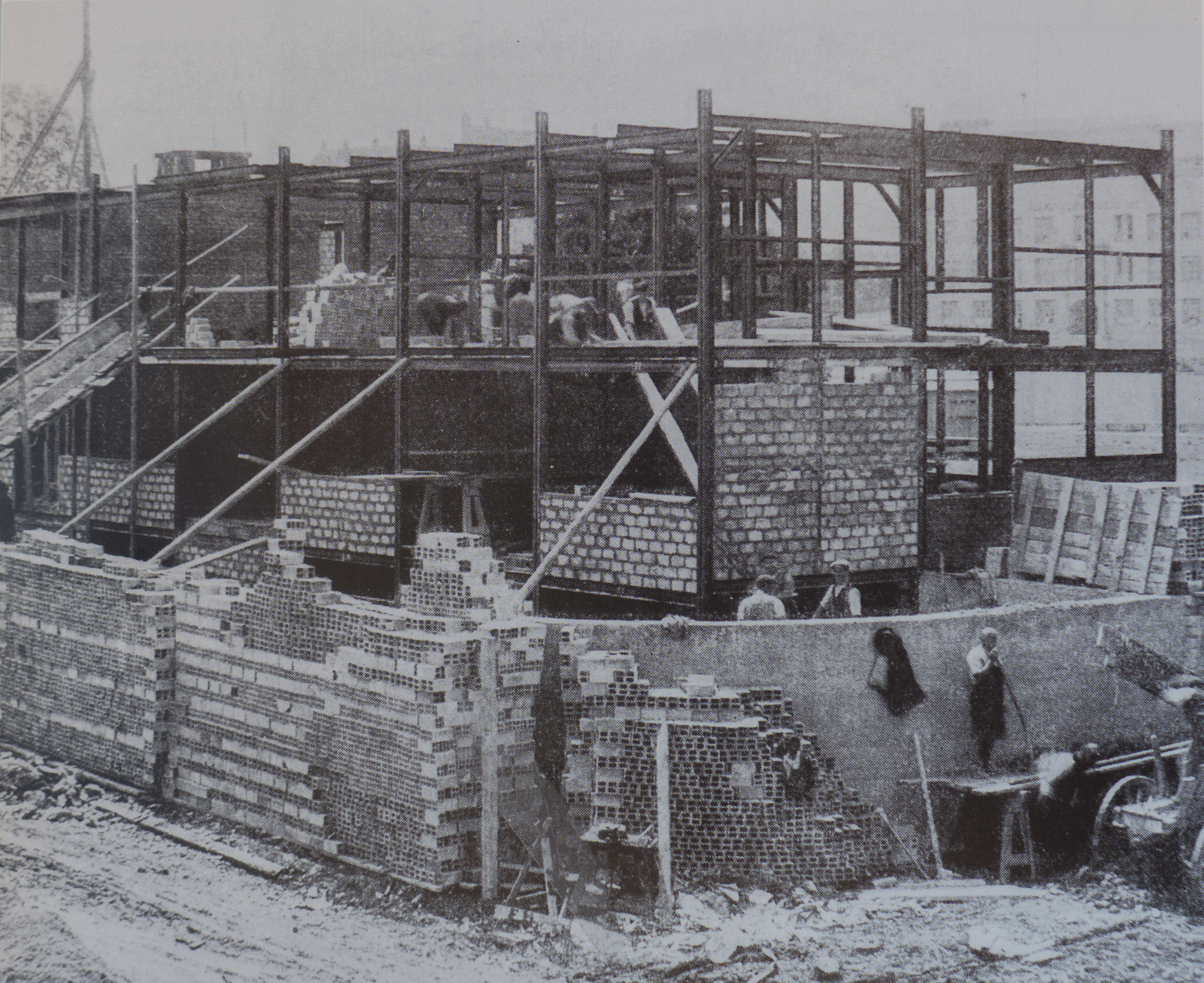

/The Deutscher Werkbund - the German Association of Craftsmen - held an exhibition in Stuttgart in 1927 that included houses and apartment buildings - the Weissenhof Estate - designed by German architects but also by architects from Belgium, France and the Netherlands. New construction techniques for domestic buildings were shown … here an open steel frame infilled with concrete blocks for an apartment building designed by Mies van der Rohe

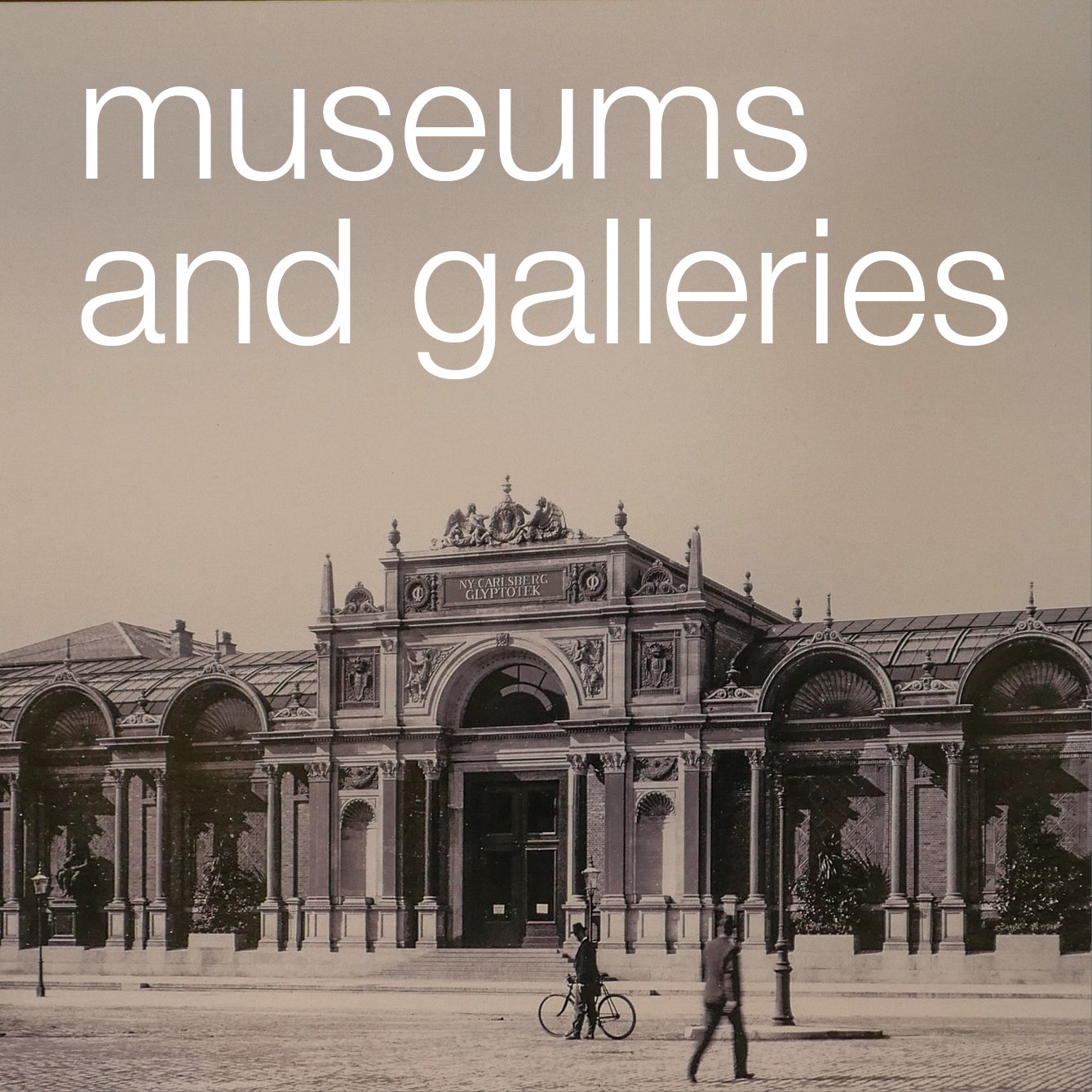

Arne Jacobsen at the SAS building during construction with Copenhagen City Hall in the background

Until the 20th century, the main materials for building construction in Europe were natural … so stone as a strong but usually expensive walling; timber for wall framing, roofs and architectural fittings including windows and doors. Natural materials were not of course always used in their found state but were modified or transformed by builders so sand for glass; plaster for covering internal and external surfaces; clay fired for bricks and roof tiles and, of course, lime for mortar and for cement. Perhaps the biggest change to the structural form and then, as a direct consequence, to the appearance of buildings in modern Denmark came with the more and more frequent use of concrete and steel … not just for industrial buildings but for housing and apartment buildings and for new large building types and particularly where high or wide and open enclosed spaces were wanted that were unencumbered by walls or internal supports.

The use of concrete and steel are now so common for building that we rarely stop to consider that both can be used in many different ways. Someone might say “… oh it’s a glass and steel block …” but that’s about as useful in helping to conjure up an impression or mental image of a building as saying that a meal was meat.

In the 1920s and 1930s steel was not always used for a complete frame of a building but could be used as simply a reinforcement for lintels and supports for wide openings but with traditional building materials for the wall itself and similarly concrete could be used for piers and frames to support large open floor spaces or it could be used poured into shuttering for panels for walls that could support considerable weight or concrete could be used cast in moulds for building blocks, used with mortar like stone or brick, or used for ornate features that could be reproduced easily and much more cheaply than when previously such features of a building were carved in stone. Above all, in terms of how the appearance of everyday buildings changed, reinforced concrete can be used with minimal support or can be cantilevered out from the facade for thin canopies or for balconies.

Arne Jacobsen’s own house in Ordrup should be seen as an important building at a pivotal stage in house design. Completed in 1929 it appears to be a modern and ground-breaking house with plain smooth white walls in the International Style that was then becoming fashionable but in fact, at that point, Copenhagen regulations did not allow concrete to be used in house building so the walls are actually built in brick and were then rendered and even the apartments at Bellavista completed in 1934 - perhaps the most iconic representation of the modern style of the 1930s in Denmark - are again brick rendered with plaster.

Jacobsen did use concrete in the Mattsson riding building just north of the apartments - also completed in 1934 - to roof over a wide high space and concrete became more and more important in his work in housing but more frequently for the industrial and commercial buildings he designed.

There is an amazing photograph taken of Jacobsen with others at an upper floor of the SAS Hotel in Copenhagen looking out over the city before the tower was clad in glass. The impression of the building now, for most people, is of a light and thinly elegant block but the outside cladding and the internal fittings cover the underlying structure and this photograph and photographs of the tower under construction show clearly a massive and robust concrete structure.

With potential problems with transport and access to the site, the concrete parts were not formed in a factory and brought to the city centre - a later and the more usual method - but the floors and cross walls were cast on site.

One obvious benefit from this substantial sub structure and the substantial internal supports is that there are no corners to the building … or rather the corners are formed by the windows and panels of the adjoining fronts being abutted to form a thin and almost invisible corner.