Poul Kjærholm was in his early 30s when he designed this chair but it is remarkably self-assured … there is clarity in the concept and a simplicity in the shape so that even today, nearly sixty years later, the chair seems to be free of conventions or styles and free of forms from the past.

This was not a matter of just stripping away decoration or just simplifying shapes and nor was it just a rationalisation to explore what is essential for a chair but, in the design of the PK9, Kjærholm re-assessed the relationship between function and the support and structure of a chair and combined that with a highly-developed awareness of shape and space.

His self confidence was more than justified: Kjærholm graduated in 1952 and from 1955 taught furniture design at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Through the 1950s he produced a number of experimental and innovative designs - a chair with one leg, a shell chair like an open clam - with two curved pieces of aluminium bolted together - a wire chair shaped like a great swoosh and these were followed by a series of chairs and tables that went into production - including the low easy chair PK22, a side chair PK 1 and a glass and steel table PK61. In 1958 he was awarded the Lunning Prize - then the most prestigious award for design in Scandinavia - and in 1960 he designed Denmark's pavilion for the Triennial in Milan.

The first winner of the Lunning Prize, at its inception in 1951, was Hans Wegner* and it was perhaps only Wegner who had as clear a view of the final form of a design - seen from all angles in three dimensions - from the first stage of the design process.

But, much more than Wegner, Kjærholm controlled how his furniture would sit in a larger space … so he considered carefully how the lines; the shapes or silhouette and the planes of a design not only define their own volume but are also defined and affected by the wider space.

From 1947 Wegner had taught at the School of Arts, Crafts and Design and after working in partnership with Ejvind Kold Christensen on several designs he introduced him to Poul Kjærholm who, at that point, was still one of Wegner’s students.

Kold, a few years older than Wegner, was the son of a cabinetmaker and had been apprenticed to learn upholstery but became a travelling furniture salesman and it was only after the War, when he met Wegner and began to work closely with him, that he became a catalyst for work with first Wegner and then Kjærholm. Kold was a businessman who understood and appreciated the importance of using the best materials and the importance of retaining the standards of skilled craftsmanship,even in metal work and engineering, but recognised the commercial potential to be gained from rationalising designs so that they could be produced in larger quantities for sale to a wider range of customers. He is credited with the idea of designing furniture so that it could be delivered in parts and then assembled to reduce the cost of shipping. Kold was important because he established a network of manufacturers to make the furniture but also marketed the work of Wegner and then Kjærholm oversees.

Kjærholm had also trained as a cabinetmaker before studying under Wegner so quality of workmanship was a fundamental part of his work. In an interview that was published in 1963, Kjærholm was asked if his furniture was designed with a view to industrial manufacture and replied that his "furniture, like most furniture at the Cabinetmakers' Guilds' exhibition, is 50% handmade and 50% industrially made. Here in Denmark we would not accept 100% industrial manufacture unless its results were technically better than the work of the hand. I will not accept a surface or material treatment of the kind found in Eames's mass-produced furniture."

But Kjærholm also studied under Jørn Utzon, who taught industrial design, and he encouraged Kjærholm to explore the use of less conventional materials for furniture and from 1956 onwards, Kold and Kjærholm worked on furniture where the main material was metal, rather than wood, with high-quality engineering techniques replacing wood and cabinetmaking skills to create new forms of Danish furniture. **

Ole Palsby - in his essay in a book on Kjærholm that was published in 1999 - made the crucial point that Kold and Kjærholm succeeded because they used metal in a Scandinavian context.

Elsewhere in Europe, through the 1930s and later, in the work of the designers from the Bauhaus and elsewhere, metal furniture was made, generally, with a frame in steel tubing, usually with a polished chrome finish, and that was not popular in Denmark. If there was any inspiration for his ideas from the work of the Bauhaus, Kjærholm looked to the work of Ludvig Mies van der Rohe for the low height and the solid weight of his furniture - for instance the Barcelona Chair of 1929 - and, more significant, to his buildings and interiors for setting furniture in formal, stark spaces.

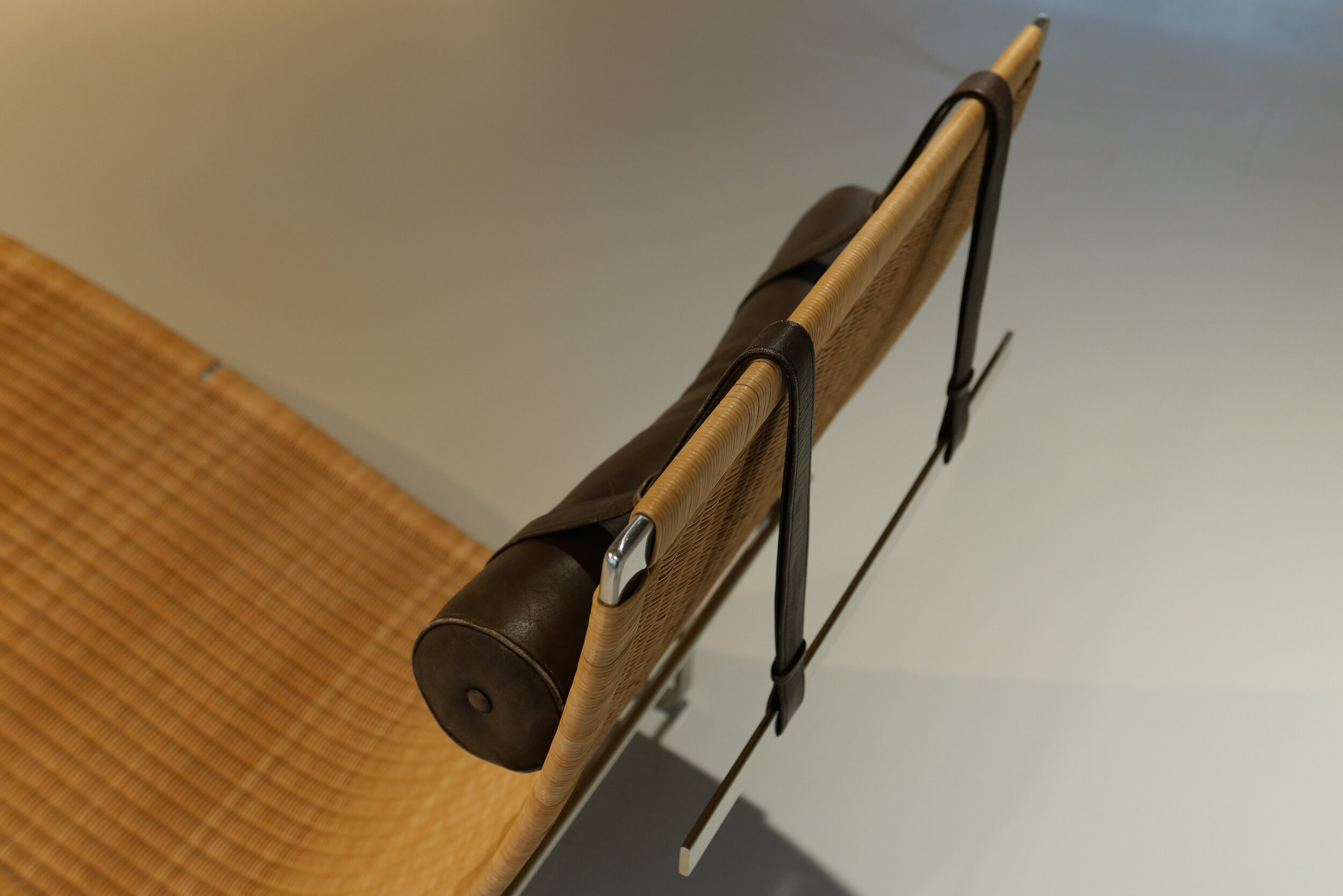

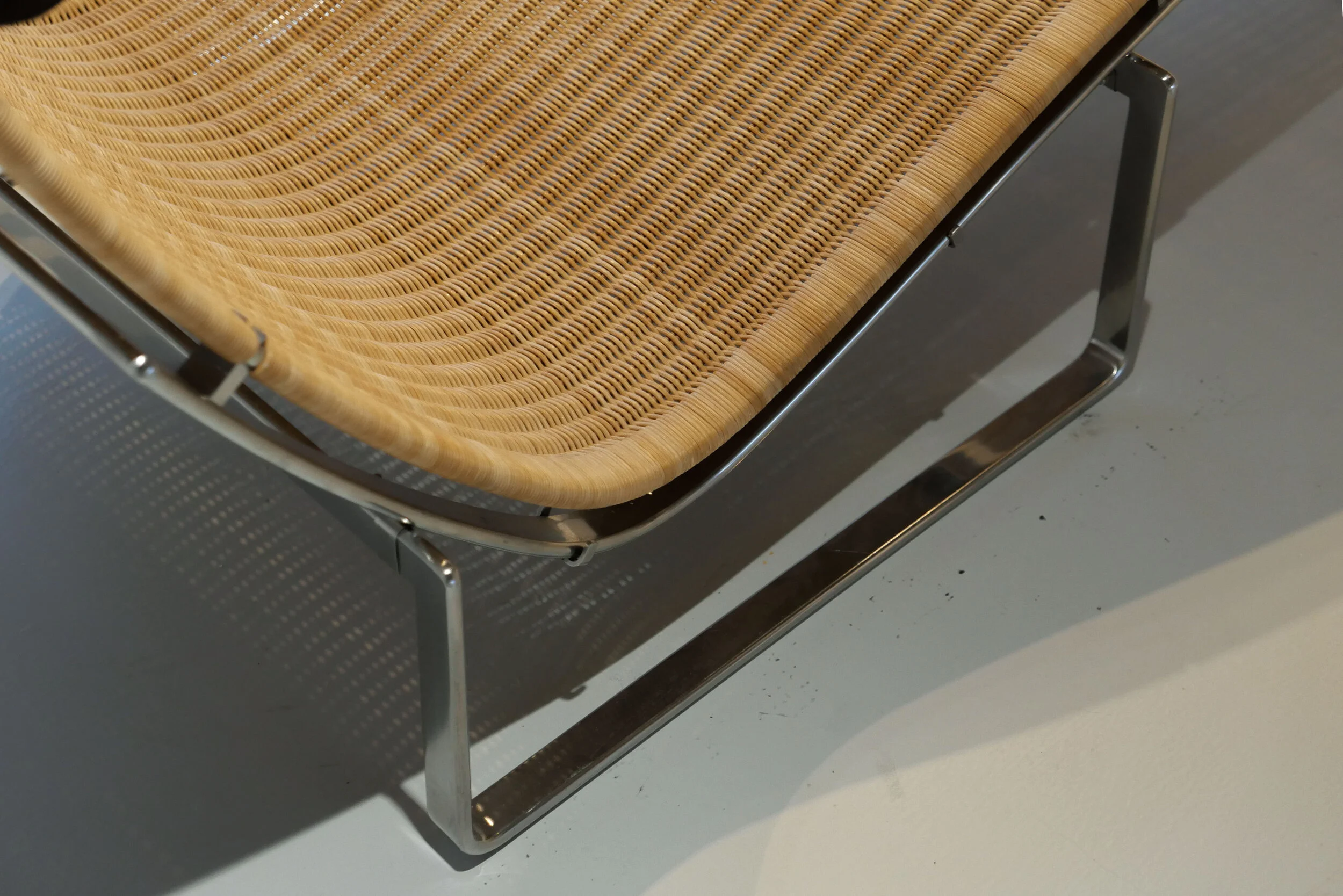

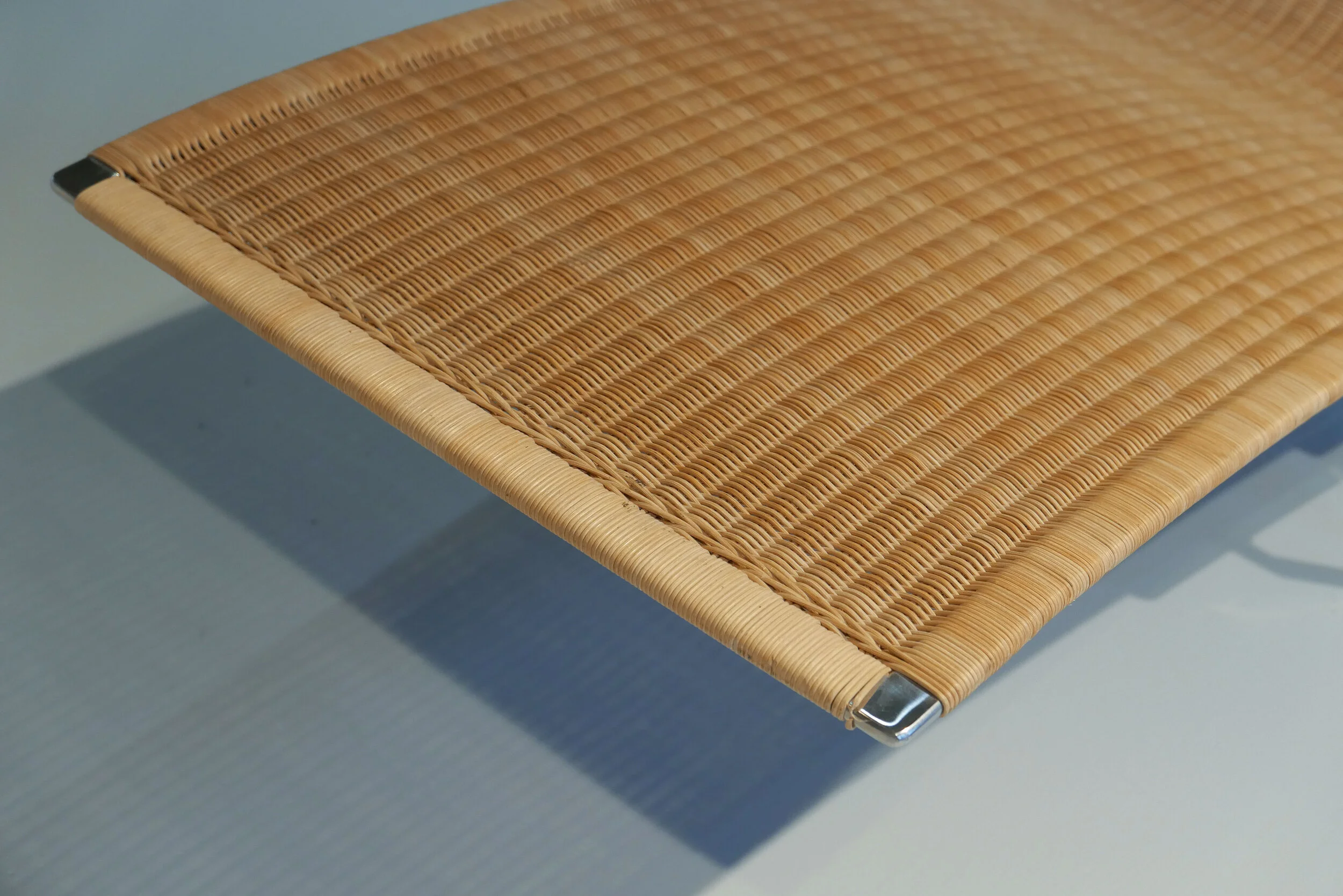

Working with Kold, Kjærholm used heavy steel in flat strips with a matt finish that had very different qualities to metal tubing and he combined the steel with high-quality leather and unpolished wood that provided a much more subdued contrast of colours and tones. Kjærholm appreciated the way that steel aged - developing a patina.

He used glass for table tops but primarily so that the frame rather than the surface dominated. Kjærholm said "I consider steel a material with the same artistic merit as wood and leather."

Rather than welding, Kjærholm used sophisticated bolts and locking nuts to join the metal parts and that reinforced the sense that these chairs and tables were an expression of precise engineering. These fixings are as important in the design process for Kjærholm as the exposed but precise joins and new ways of bending and shaping wood that Wegner developed in his collaboration with cabinetmakers.

It would be a mistake - in emphasising the engineering and the architectural aspects of his work - to loose sight of the fact that Poul Kjærholm trained and began his career as a cabinetmaker and understood not just the importance of using the best materials but also the importance of working with the best craftsmen to produce his furniture. He worked with the metal smith Herluf Poulsen; with Ivan Schlecter for upholstery, particularly leather, and with Ejnar Pedersen, founder and owner of the cabinetmakers PP Møbler, for work in wood.

Ole Palsby made another important point when he observed that furniture by Kjærholm is "generally smaller, low and transparent, making man the most important part of the room" and observed that Kold "believed to the end that artistic quality can sell, that production with an artistic intention was marketable."

Kjærholm designed the displays in Bredgade at the showrooms of E Kold Christensen where the furniture was shown against large black and white photographs of open landscapes and this format was repeated for an exhibition in Paris where the space was precisely divided and controlled with lines of pendant lights forming a cross to divide the main space and furniture was placed precisely to show the importance of the space around each piece.

In 1965 Kjærholm designed the display for an exhibition of his work held at the showroom of Ole Palsby in Hovedvagtsgade in Copenhagen.***